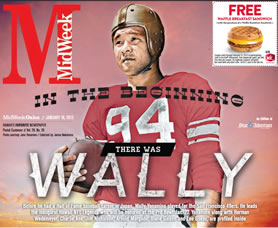

In The Beginning There Was Wally

Before he had a Hall of Fame baseball career in Japan, Wally Yonamine played for the San Francisco 49ers. He leads the inaugural Hawaii NFL Legends who will be honored at the Pro Bowl Jan. 27. Yonamine along with Herman Wedemeyer, Charlie Ane, Jim Nicholson, Arnold Morgado, Blane Gaison and Leo Goeas, are profiled inside

During the National Football League’s Pro Bowl Jan. 27 at Aloha Stadium, for the first time the NFL will honor former players from Hawaii. Dubbed the Hawaii NFL Legends, the seven were chosen by the local Pro Bowl host committee, based on performance, accomplishment and character on the field and off it. MidWeek is pleased to have the exclusive on this inaugural class of honorees: Wally Yonamine, Herman Wedemeyer, Charlie Ane, Arnold Morgado, Jim Nicholson, Blane Gaison and Leo Goeas

cover_5

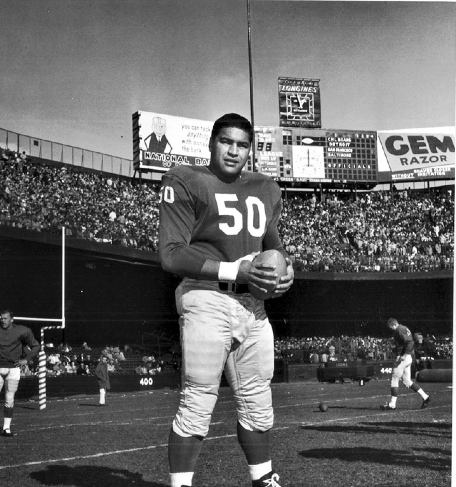

Charlie

Charlie Ane was a big man, and not just in a physical sense. Ane's success in football opened the door for generations to follow in the NFL. More important, his 40-year career as a high school football coach and athletic administrator provided opportunities for thousands of young student-athletes. Most important, in 1960, in the midst of a Pro Bowl career in which he helped lead the Detroit Lions to three division titles and two NFL Championships, he retired from professional football to bring his young family back to Hawaii.

"There were two reasons why my mom wanted to bring us home, to know our grandparents on both side and to go to Punahou," says Ane's daughter Malia. "They both were from Punahou and our family was from Punahou."

Of course, players' salary wasn't the same in the 1950s.

"I don't think he ever made more than $7,000," says son Kale, the current Punahou football coach who followed his father to the NFL.

Even though the decision was the right one for his family, the move did separate him from a group of friends whose bond was lifelong. Which Malia got to see firsthand when she accompanied her parents to team reunions in Detroit.

"They just loved to play, they loved each other," she says of the old Lions. "They took care of each other, they raised their kids with all of us. One funny thing I remember, whoever was the rookie on the team that year, was still the rookie. 'You buy the drinks, you call for the taxi.' Unbelievable. I saw the depth of that kind of friendship so many years later. Daddy's roommate still called him Roomie."

Carrying the Ane name in Hawaii athletics comes with a level of expectation. Never, however, from Charlie, who when the conversation turned to his own career, would quickly change the subject to his children or other kids he coached.

"He understood he was a big shot, so he tried to protect us," Malia says. "But we always had to deal with it. That's just the way it was. We couldn't ignore it. You have to be proud of it, respect it but make your own path. Now as a parent you realize what a great message that is."

If there was a downside to all his modesty, it was that his children never really knew how good their father was until they were much older.

"We never really knew how good he was because he never told us," says Malia, who played volleyball at BYU.

-Steve Murray

Honolulu Star-Advertiser photo

Wally Yonamine was first. In so many ways.

As the National Football League prepares to honor seven Hawaii men who made it in professional football, Yonamine is first among them. The Farrington High alum is the first athlete of Hawaii birth, and the first person of Asian ancestry, to play pro football at the highest level. Yes, the man eternally enshrined in the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame, and for whom the Hawaii high school baseball championship tournament is named, first played for the San Francisco 49ers.

Which turns out – as history-changing and dreams-altering as it was for so many people – to be almost the least of Yonamine’s firsts.

While this is much more than a sports story, it does affirm the transformative power of sport, and of boyhood dreams. And it’s a story that set the stage for the many young men who were to follow in his cleat marks. How many? The website databaseFootball.com lists 67 local boys who have played in the NFL. Wally Yonamine led the way.

(A brief aside regarding historical firsts: “Honolulu Johnnie” Williams, of native Hawaiian ancestry, pitched four games for the 1914 Detroit Tigers, making him – it is believed – the first island-born athlete to play in a major U.S. professional league. Walter Achiu did play the 1927-28 seasons for the NFL’s Dayton Triangles after attending the University of Dayton, but the NFL of those days was far from a major league.)

It was 1947, and wars in the Pacific and Europe were barely two years ended. In San Francisco, emotions were still raw as thousands of Japanese – most of them American citizens – who had been rounded up and forced from their homes and businesses in The City’s thriving Japantown returned from desolate internment camps.

In Wally Yonamine, San Francisco 49ers rookie running back, they found a dashing young hero on whom they could hang their new hopes.

“He made us proud that we were Japanese,” Hats Aizawa remembered nearly 50 years later. Quoted in the English-language Bay Area newspaper Nichi Bei Times in 2005, Aizawa, 77, who had attended Yonamine’s games at Kezar Stadium with other young nisei (second generation), continued: “He had this burst of speed … he was fast. He left me with a lot of pleasant memories.”

The paper also quoted Warren Eijima, 81: “To see another Japanese-American play made me feel good.”

So Wally was a powerful symbol for Japanese rebuilding lives and businesses – many having found strangers of other ethnicity now living in homes and running stores and restaurants they’d been forced to abandon. In that, he was also first.

“Wally always said he had to do well because of all those from the internment camps coming back to San Francisco who were rooting for him to do well,” his widow Jane recalls.

At the same time, for many San Franciscans who served in the war or lost a loved one in it, and referred to Japanese people by the J-word, he was also a symbol that the war was over. Here was a Japanese man for whom they could stand and cheer. They were now on the same side. That too was a first.

For both groups, Yonamine’s presence in a 49er uniform was a turning point of sorts.

As a 49ers reserve running back in the autumn of ’47 (the team’s second year of existence), he started three games and averaged 3.8 yards per carry and 11 yards per pass reception for Coach Buck Shaw. As a defensive back in those days of ironman two-way players, Yonamine had one interception.

“Football, that was Wally’s first love,” Jane says. “That was the only sport he ever really loved. Years later, when people asked about the old days, the first thing he mentioned was football.”

Looking ahead, he and the 49ers had every reason to be optimistic about the 1948 season.

(In those years, the 49ers – wearing snazzy red-and-white uniforms and leather helmets – played in the eight-team All-American Football Conference, which stretched from New York to Los Angeles. In 1950, the Niners along with franchises in Cleveland and Baltimore joined the NFL, breathing new life into the league, much as the NFL-AFL merger would do a generation later.)

It started on the sugar plantation at Olowalu, Maui. Born Kaname Yonamine on June 25, 1925, the boy who would become “Wally” was the third of seven children born to Okinawa-born Matsusai Yonamine and Maui-born Kikue Nishimura, whose parents had emigrated from Hiroshima. (In Japanese, kaname is the single nail that holds a fold-out fan together. “And that’s who he was,” Jane says.)