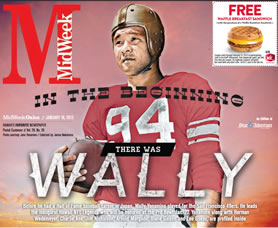

In The Beginning There Was Wally

Despite his father working hard from dawn to dark on the plantation, and being promoted to a variety of better jobs, life remained hard, and putting food on the table for a growing family a challenge. The family was so hard up, Wally recalled later, “my parents couldn’t afford to buy us a stick of candy.”

Likewise, there were no toys. So he and his brother Akira ran around, literally. Akira, two years older, was the fastest kid on the plantation, and Wally was right behind. Akira’s Maui record for the 40-yard dash stood for decades.

cover_7

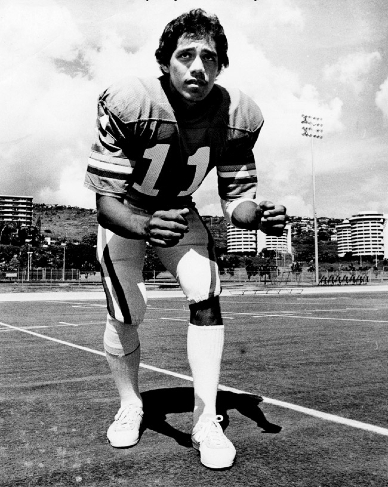

Blane Gaison

We all know the story: the young boy playing ball with his friends, pretending to make the game-winning catch, the fans in his mind roaring their approval. Most of us have had the fantasy, or at least heard the cliché a thousand times.

But not Blane Gaison. Even as the nephew of Herman Wedemeyer, he didn't know he was allowed to have such aspirations.

"For me, a kid growing up in Kalihi, it wasn't a dream I ever dreamed," says Gaison, who spent four years playing defensive back for the Atlanta Falcons. "I never had any idea or intentions to play in the NFL."

His lack of vision in no way impeded his talent, as he rose through the ranks to become the quarterback at Kamehameha, leading the Warriors to back-to-back state championships in 1974 and '75.

True to his roots, he stayed home to play for his hometown 'Bows, switching over to the defensive side of the ball to play cornerback, where he stayed except for one pivotal game against Colorado State. The team was down at halftime, and to mix it up the coach told Gaison to go change helmets, he was going in at quarterback.

"We came back out with like three run plays and two pass plays, and just did those and came back and won the game," recalls Gaison with a laugh.

He got drafted by the Falcons in 1981, a team that featured backup quarterback June Jones and defensive coordinator Jerry Glanville, and suddenly the boy from the streets of Kalihi was playing against competition he had never even allowed himself to dream about.

"I remember listening to the national anthem and looking across the field and seeing Terry Bradshaw, Mean Joe Greene and Lynn Swann, and knowing I am going to play against them in a minute," says Gaison. "They are history! What a real joyride, a wonderful journey."

After his career, he returned home to work at Kamehameha Schools in the athletic department on the Kapalama campus, but on Jan. 1 moved to Maui to become the new athletic administrator at Maui KHS.

He loves his position, being able to help influence young people's lives, much as his Uncle Herman helped to influence his own.

"I never got to see him play, but one of the things we always talked about was the passion," says Gaison of Wedemeyer. "Whatever sport it is, you are playing to have the passion for the game and being the best. Give nothing less than your best."

C.P.

Honolulu Star-Advertiser photo

The authoritative 2008 book Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball by Robert K. Fitts (University of Nebraska Press) includes an anecdote about the hungry, adventurous Yonamine boys stealing a watermelon, despite getting fired at by a shotgun-toting farmer. They soon gravitated to sports, whatever the season was.

“He was a rascal,” Jane says. “Nothing really bad. Mostly, Wally was so busy with sports, he didn’t want to do school-work.”

That is how, out of seven siblings, he was the only non-Buddhist.

“His uncle took him to the Catholic church to straighten him out,” Jane says.

His faith stayed with him, which is one reason he and Jane bought a unit at Kahala Nui retirement center, so he could walk to morning mass every day at adjacent Star of the Sea church.

In his book, Fitts writes “the Yonamine brothers played softball, volleyball, soccer and Wally’s particular favorite, football. Since they didn’t have enough money to buy a football, they took an (empty) can of Carnation creamed corn, wrapped it in newspapers, and used that instead.” And because there were few teen boys in the area, the Yonamine brothers joined men’s games.

A radio was Wally’s first window into a world beyond plantation life, and he especially enjoyed listening to games of the semi-pro Hawaii Baseball League and ILH football games from Honolulu Stadium. Listening to games, often with his grandmother, he began to dream of playing in the big city.

As a teen he worked summer days on the plantation, cutting sugar cane.

“I used to really hate that job,” Wally told Fitts. “I got paid only 25 cents a day, but it was the only job I could find. I told myself I never wanted to work in the cane fields again. That’s where my drive to always try my best and never give up came from.”

Wally boarded at Lahainaluna High School for his freshman year, and with other boarders worked three hours on the school farm before classes. His job was to personally bring in 100 pounds of grass a day for the farm’s cows. He went out for the football team in that autumn of 1941 and was named to the second team. But in the first game – against Roosevelt of Honolulu – a Lunas running back broke his thumb, and the coach put in Wally. On his first play, after taking a lateral pitch, Wally threw a 35-yard touchdown pass. He later ran 11 yards for another TD and scored again on a 70-yard interception return.

The Lunas went 6-0 on Maui and hosted Oahu champions Saint Louis in the Haleakala Bowl, which drew 4,000 spectators to the Kahului Fairgrounds. The star for Saint Louis was “Squirmin’ Herman” Wedemeyer – as it happens another inaugural inductee into the Hawaii NFL Legends. The city boys prevailed with two late scores, 13-0.

Wally again worked the sugar fields the following summer and returned for his sophomore season at Lahainaluna. With him running and passing out of the single-wing formation, and kicking, punting and returning kicks, the Lunas again won the Maui title, going 5-0-1. In the deciding final game, Wally scored all 19 points in a 19-6 win over St. Anthony.

On Maui, he was the best player on any field stepped, but he couldn’t get the dream of playing in Honolulu Stadium out of his head. So he asked his father if he could move to Oahu. Having himself left Okinawa at 17, Matsusai said, “If you want to go, you go.”

He went, moving in with an older sporting friend from Olowalu, Mac Flores, now a stevedore.

Wally could have attended Saint Louis – just picture him in the same backfield with Squirmin’ Herman – but instead enrolled at Farrington in the fall of 1943. It was there Kaname adopted the name Wally – after the school’s namesake, Gov. Wallace Rider Farrington. It was frustrating having to sit out his junior year after transferring, and he was never sure where his next meal would come from, but he worked out regularly with Farrington equipment manager Arthur Arnold (who’d also suggested the name change as a way of fitting in) and was ready for his senior season.

Imagine his thoughts and emotions as he ran onto the field for his first game at Honolulu Stadium, which at capacity held 26,000 spectators, his boyhood dream about to come true. Kamehameha was the foe, and wearing a white No. 37 Govs jersey Wally kicked a field goal to open the scoring, later prevented a Kamehameha score with an interception, scored on a run early in the third quarter and added the extra-point kick, giving Farrington a 10-7 win. As in his final game on Maui, in Wally’s first game on Oahu he tallied all the winning points. He would repeat that feat several times during the season, and was named the Honolulu Advertiser‘s league MVP.

Wally turned 20 the following summer and was drafted into the U.S. Army. But the war in Europe was over and Japan would surrender six weeks after he started basic training at Schofield Barracks. It was there he caught the eye of Pittsburgh Steelers coach Jock Sutherland, who had played college ball at Pitt under the legendary Pop Warner. Sutherland offered Wally a contract with the Steelers, but he declined, saying he wanted to attend college – he had scholarship offers from USC, Ohio State and St. Mary’s (where Wedemeyer was starring).