The Lifeline of Hawaii

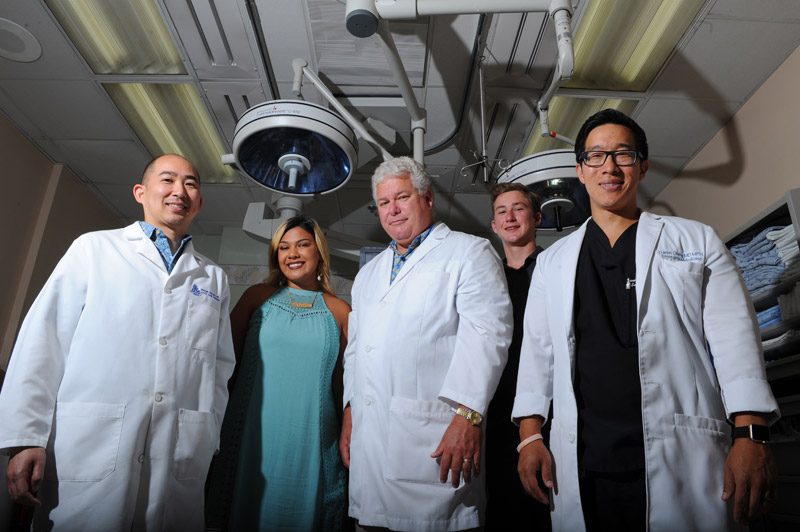

Dr. Michael Hayashi, patient Alisha Brown, Dr. Howard Klemmer, patient Ian Guard, and Dr. Daniel Cheng

Welcome to The Queen’s Medical Center, home of the state’s busiest and most skillfully operated emergency department, where lives matter and every second counts.

When then-18-year-old Alisha Brown arrived at The Queen’s Medical Center Emergency Department after getting hit by a car, no one — not even her doctors — were sure that she would fully recover. Brown was unresponsive upon arrival, her brain dangerously swelling, and it was nothing surgery could fix.

So doctors took other routes to care for her brain: enacting a hypothermia protocol to cool it down; administering medicine to remove water and reduce swelling; and inserting a device that measured its pressure and oxygen levels.

Then, they waited.

The Queen’s Medical Center at night

After a few weeks, Brown woke up. Now, at 19, she’s still on the road to recovery but back in school.

Brown remembers almost nothing from the accident, but one key detail that was passed on to her has left a lasting impression.

“One of the doctors, they took my parents to a room and they said, ‘We don’t know what’s going to happen, but I’m going to treat her like my own daughter,'” she says.

“That was Dr. Nakagawa,” interjects her mother, Lily.

Admittedly, Dr. Kazuma Nakagawa — medical director, Obstetric Neurovascular Service, Neuroscience Institute — was just doing his job.

Emergency Department nurse Melissa Derry, RN, at work PHOTOS COURTESY THE QUEEN’S MEDICAL CENTER

“Deep down, I wasn’t sure if she was going to make this kind of recovery,” says Nakagawa. “It’s one of those cases that we’re just doing what we do every day.”

Stories like these are not uncommon for the medical center’s highly skilled staffers who work in the Emergency Department and provide trauma services. In another case a couple of years back, a turn at the helm of a Jet Ski landed teenager Ian Guard in the Emergency Department. Like Brown, his case was severe and his recollections of what happened are fuzzy, coming mostly from the memories of others. But as Guard and his mother, Allison, run down a list of the damage done to his body — a broken neck and vertebrae, subdural hematoma (bleeding between the brain and skull) and both lungs punctured — one thing becomes clear: Had Guard not been rushed to Queen’s, he may not be alive today.

“He got such good care that it gave him the opportunity to heal,” says Allison. “They kept him safe, they communicated with us — they were there, as a hospital is, 24/7.”

Being there for Hawai‘i is exactly what the Emergency Department at Queen’s is for. It’s where the sickest of the sick go, as Dr. Howard Klemmer, chief of emergency medicine, puts it — a place that boasts the only comprehensive stroke and trauma centers in the state that are led by board-certified, residency-trained physicians. With Queen’s at Punchbowl logging about 12.5 percent of all emergency room visits statewide each year, or roughly 66,000 patients, it is the busiest emergency department in Hawai‘i — and its staff is equipped to handle just about everything.

Dr. Michael Hayashi, patient Alisha Brown, Dr. Howard Klemmer, patient Ian Guard and Dr. Daniel Cheng

Not all physicians who work on emergency cases are Emergency Department doctors. These doctors deal with all patients who enter the emergency room, and each case is assessed to determine whether it is trauma-related or not.

Sometimes, Emergency Department doctors treat a patient without the help of others. As the hospital explains it, regardless of the type of case, the department serves as a receiving service for all patients, and care begins there. But when trauma patients do enter for treatment — in instances of an injury caused by, say, a gunshot wound or major car accident — people like Dr. Michael Hayashi are paged.

Hayashi is not an Emergency Department doctor. He doesn’t live there full time, as he puts it. He’s a general surgeon with fellowship training in surgical critical care, and the trauma medical director for Queen’s (trauma is a sub-specialty of general surgery that requires further training, according to the hospital). Hayashi estimates that the trauma center gets called to assist the department with about 2,600 patients that present varying degrees of injury each year. When he does get that buzz or hears an announcement from the hospital that a trauma patient is moments away, it’s time for Hayashi to hustle.

“Everyone will come running down,” he says.

In extreme circumstances — there are different levels of severity — the trauma services team that assembles might be comprised of everyone from a trauma surgeon and chief resident to an anesthesiologist and the ICU team. It all makes for what sounds like something straight out of an episode of ER or Grey’s Anatomy. But contrary to depictions in pop culture, Hayashi says that, like almost all occupations, there are lulls right alongside bursts of action. Hospitals are full of drama, just not the kind you might expect, and certainly not as glamorous.

“You can go from taking care of a little girl who has a sore throat, to somebody who’s just gotten in a major car accident and is about to die and needs surgery, to somebody who’s suicidal and feeling like killing themselves, to someone who’s got a urine infection,” says Klemmer. “The day is filled with diversity and challenges. We like to say the term, ‘It’s where minutes matter and seconds count.'”

“It’s a little bit of everything,” adds Dr. Daniel Cheng, medical director of the emergency room and assistant chief of emergency medicine. “There’s comedy, there’s a lot of sorrow — I think controlled chaos with the extremes of human grief and human suffering, with complete jubilation and joy when you can bring someone back from the depths of despair.”

In the midst of all this, there is one thing that keeps the Emergency Department and its trauma services staff running smoothly: teamwork.

“We’re cohesive,” says Nakagawa. “We work as one team even though we have so many different people — neurosurgeons, trauma surgeons, ER docs and so on. A lot of other places, they have their own politics and egos and whatnot, but here, we are truly like one family.”

That, says Klemmer, boils down to the nonprofit hospital’s mission-driven mindset.

“That makes all the difference,” he says. “Their mission is to care for the people of Hawai‘i in perpetuity.”

“When we have mission-driven hospitals like Queen’s, where it’s really fundamentally focused on the (vision of) Queen Emma, which is caring for the sick, the indigent, the Native Hawaiian population — when the focus is on that, it provides a cultural approach to patient care that heightens what we do,” adds Cheng.

Dealing with patients is not the only task some Emergency Department doctors undertake, though. As Klemmer explains, some also conduct hyperbaric treatments, run a wound care center or put academic degrees in public health to use.

Cheng, for example, does a lot of work with the homeless population in Hawai‘i. By his estimate, Queen’s cares for about 64 percent of all homeless individuals — a much higher average than other hospitals in the state. Providing care to these people is vital, he says, but what happens after?

To better help those it serves, the hospital is embarking on what it calls The Queen’s Care Coalition. Within the next several years, it hopes to have a network of aid set in place —a combination of both medical and community outreach services, providing a continuum of care to homeless patients.

“Queen’s has been stepping up to the plate,” he says. “I’ve been really happy … as an ER physician, that Queen’s has really dedicated themselves to putting their actions where their mouth is — this culture, this mission by Queen Emma: care for the indigenous, the sick, the poor.”

But that isn’t the only thing that Queen’s hopes to accomplish in the coming years. It’s been almost two decades since Queen’s unveiled a renovated Emergency Department in 1999. Spanning 25,000 square feet, it currently is compromised of 31 treatment rooms.

“It was designed to serve what we felt were going to be the needs of the patients over the next, what we thought would be, the next several decades,” says Art Ushijima, president and CEO of The Queen’s Health Systems and president of The Queen’s Medical Center. “I think it was pretty cutting edge back then, and I think it’s still pretty relevant today.

“We have an emergency room that’s really designed to serve multiple health care (and) medical needs, whether they’re acute strokes and heart attacks to patients with behavioral issues,” he adds.

Despite this, Ushijima says that the time has come for Queen’s to plan for yet another expansion. With the number of patients it receives each year, it’s a growth that only seems natural — more room for an increasing demand, in fact, is a challenge Klemmer says the Emergency Department faces.

But getting there is going to take some time. To start, Queen’s is hosting a sold-out benefit dinner Sept. 8. Proceeds will support the future expansion of the Emergency Department and its trauma services, helping with the renovation, construction, and purchasing of new medical equipment and technology.

“It’s a longer-term plan,” says Ushijima. “It’s going to take a lot of planning and certainly a lot of costs, but I think the growth and demand for emergency services will continue to expand.”

More importantly, though, Ushijima hopes that the community realizes just how vital its emergency services are.

“We do need the public’s support so that they know they’ll get taken care of in the best possible way,” adds Hayashi. “Hopefully, they’ll never need us. But if they do, then we’re here for them.”