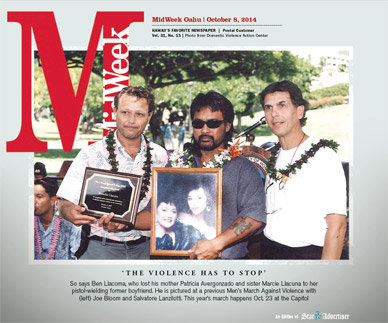

The Violence Has To Stop

It’s crazy, right? To love someone who’s hurt you? It’s crazier to think that someone who hurt you loves you. —novelist Jodi Picoult

Domestic violence is news. But what about the many unpublicized situations that exist in silence?

To the victims or concerned associates who read this story in fear and frustration, we have a message: Put aside your distress and shame for a moment and be courageous enough to face your plight and listen to those voices of concern.

One such voice in our community is Nanci Kreidman, chief executive officer of Domestic Violence Action Center of Hawaii (DVAC). We asked Kreidman to tell us about this social ill that is rearing its ugly head in headlines.

Coincidentally, October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

It’s a questionable declaration, to be sure. Is it a form of civic plight or pride?

For journalists, this is a tough assignment. How does one write an objective story about domestic violence and not get emotionally caught up in the angst of the issue? How does one maintain composure when uncovering that her colleagues, including a MidWeek columnist and local TV news anchor, are survivors of domestic violence?

Yet Kreidman faces the anxiety and complexity of domestic violence cases daily. We gingerly enter her world of activism and advocacy.

To those caught in the web of domestic violence, she first declares:

YOU ARE NOT ALONE

* An estimated 1.3 million persons are victims of physical assault by a partner each year, according to National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

* Eighty-five percent of those victims are women.

* Most cases of domestic violence are never reported to police.

* One in every four women will experience domestic violence in her lifetime.

If that isn’t alarming enough, consider the economic impact:

* The cost of domestic violence exceeds $5.8 billion each year, $4.1 billion of which is for medical and mental health services.

* Victims of partner violence lost almost 8 million paid workdays.

* This loss is equivalent to more than 32,000 full-time jobs and almost 5.6 million days of household productivity.

“The bottom line is that everybody loses, and the quality of life in a community suffers,” Kreidman says.

But the victims of domestic violence are numb to numbers.

They are engaged in a lonely battle of the battered where domination and intimidation by a mate is a pattern in life. Victims can be female, male, heterosexual, gay, married, separated or dating. Domestic violence does not discriminate. It occurs in every social, economic and ethnic sector of our community.

It breeds in a society where the use of force and aggression is depicted by idolized action heroes in movies, books, video games and sports.

“There are intergenerational cycles of abuse that condone violence,” Kreidman reveals. “Children who live in a household with violence may continue the legacy of abuse when they reach adulthood.”

Yet the problem often is overlooked, excused or denied. It hides under a veil of secrecy, shame, fear and even cultural morality. It is said to be the most misunderstood form of abuse.

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

“Noticing and acknowledging the signs of an abusive relationship are the first steps to ending it,” Kreidman says. “No one should live in fear of the person they love.”

Perhaps in no other human interaction is love used as an emotional wedge and leverage to dissect destructive behavior.

As victim Antonia M. puts it: “Even after being harmed, I would think he didn’t mean to do it. When he told me that he would never do it again, I always believed him. I had to believe him. I was dependent on this man emotionally, psychologically and financially.”

The physically abused have bruises and scars as badges of shame. Fearful and embarrassed of these overt signs of violence, they lie to friends and family to hide the truth.

“Abuse takes place in many forms, both physical and psychological,” Kreidman explains. “We have clients who tell us that their spouse does not hit them. But their name is not on the title of the house, bank accounts or credit cards. They are monitored day and night. They feel powerless and controlled.”

The individual’s self-worth is demeaned. They are isolated and marginalized.

Some situations end fatally, as they did in the separate shootings of Lynn Kotis and Sherry Morioka in 1992.

TO STAY OR NOT TO STAY

The most dangerous time in an abusive relationship is when one decides to leave.

“Leaving is not a one-step process,” asserts Kreidman, a New Jersey native who moved to Hawaii in the 1970s. “It’s a long journey once one musters the courage, and there are continuous steps in a system that isn’t all that helpful.”

It underscores the complexity of domestic violence and the limitations of what legal and social outreach can offer in a fair and equitable manner. Even the stories and state of mind of victims can waver while going through the maze of the separation process.

The welfare of children and the breaking up of a family unit adds to the drama. Being an island community is a barrier, too.

“It’s hard to get away and not be detected,” Kreidman says. “It’s not as simple as driving to the next state.”

For the safety of both staff and clients, the location of the DVAC office is rarely publicly disclosed. It is confidential, as are its client cases and HelpLine calls.

HOPE AND HELP

The safety net of services for battered partners is not structured ideally for robust or consistent solutions, critics say. DVAC is the best clearing-house for referrals.

“There is help and hope here,” assures Kreidman, whose career has included establishing the state’s first shelters for battered women.

DVAC can help with a safety plan to escape violence. This includes where one goes, how to get there and what to bring. Friends and neighbors know about what is going on so they may assist in calling for help if something happens.

During a violent episode, police should be called and given as much information as possible. After all, domestic violence is a crime. DVAC’s legal HelpLine (531-3771 on Oahu or toll-free 1-800-690-6200) provides referrals and procedures for getting temporary restraining orders, applying for child support, reporting child abuse and using the justice system.

Employers, health care professionals, teachers and other community professionals are welcome to call with questions. DVAC’s teen advocates assist with resources, information and support for young people in abusive relationships.

“It’s a delicate subject,” Kreidman says of domestic violence. “That’s why we have so much difficulty engaging the community, including getting support and cooperation.”

The nonprofit agency that operates with a staff of 48 and an annual budget of $2.5 million derives only 2 percent of its revenue from client fees. State and federal funds, plus grants, finance its outreach services and programs.

“The requests for help are steady, and there are no signs that the problem is going away,” Kreidman notes. “We must inspire the community to have the conversation and build a deeper understanding of how to ensure safe families and homes.”

The word to batterers is less complex and more blatant:

Stop the violence.

ENOUGH IS ENOUGH

Join the dialogue and voices of concern:

* Men’s March Against Violence. Thursday, Oct. 23, at noon at the state Capitol with a 12:30 p.m. rally at Skygate Park, City Hall grounds. Sponsored by Catholic Charities Hawaii, Domestic Violence Action Center, City & County of Honolulu, Kaiser Permanente, Kapiolani Community College, YMCA and PHOCUSED.

* DVAC 2015. DVAC celebrates its 25th anniversary next year with a series of public events. Say mahalo to the organization devoted to prevention and intervention of domestic violence. Honorary chairwomen are Jade Moon, Jackie Young and Annette Amaral.

* For information and videos: stoptheviolence.org.