All Creatures Living and Dead

State veterinarian Dr. Jenee Odani checks the health of live animals – such as these happy critters at Nozawa’s Ark in Kaaawa – but when they get sick and die of unknown causes, it’s her job to find out why. If this were TV, they’d call it Animal CSI

Never let an editor give you a one-word assignment, then leave town for a vacation. Particularly if the word is necropsy, and you don’t know the definition.

Does it have something to do with necks? Or is it what one suffers from too many naps in the afternoon?

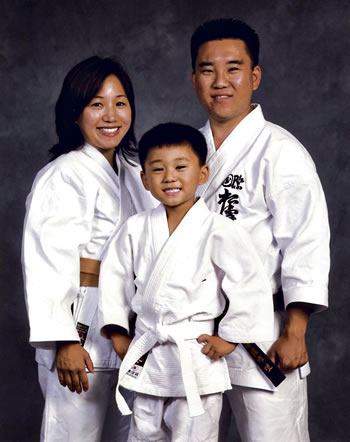

Dr. Jenee Odani With husband Norman and son Nicholas

To find out, we head out to the state Department of Agriculture Veterinary Laboratory in Halawa. There, on a gray building, is a sign with that strange word: Necropsy.

If it had been a dark and stormy night, we would have turned back immediately after seeing these words posted on the door: “Do Not Bring Blood Samples Into This Room.”

It is a harbinger of things to come.

As we enter the reception area, we see a large museum-like display case along the wall. We gasp at the horse and pig skulls set among rows of labeled bottles. In the bottles are animal parts and internal organs preserved in formaldehyde. One is labeled “Coral Farm Hog Cholera. 7/7/61.” Another is tagged “Deer Tuberculosis.” Yet another is marked “Feline Cyclops. Stillborn October 1975.”

Is this the little shop of horrors?

No, dear readers, it is our way of meeting someone with a unique job and discovering a relatively unknown state government function that helps protect our agricultural industry.

Jenee S. Odani, DVM, is a veterinary medical officer with the state Department of Agriculture. She is the only practicing board-certified veterinary anatomic pathologist in the state.

Her first name is pronounced “Je-NAY,” like Renee with a J. That’s a lot easier to say than her profession. Necropsy, pronounced “neck-rop-see,” is the postmortem (after death) examination of animals. That’s right. Animal autopsy.

But there’s a difference. A human examining a human cadaver is said to be doing an autopsy. A human doing an examination on an animal cadaver is said to be doing a necropsy.

Get it straight because there will be a test later.

“I guess folks think pathologists are weird and creepy,” says Odani, who’s anything but. The perky 39-year-old Pearl City resident has credentials and experience as a veterinary pathologist that are impressive.

She’s originally from Maui, graduated from Baldwin High School and grew up in an agricultural community.

“When you grow up on a Neighbor Island, the land is your lifestyle,” she says. “At one point, I wanted to be an agricultural engineer and work for Maui Land & Pineapple.”

She attended the University of Hawaii, where she was a regent scholar, then studied zoology at the University of Washington. She was awarded a doctor of veterinary medicine (DVM) degree from the University of California-Davis in 1999. Her residency in diagnostic veterinary pathology was at the UC-Davis Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory in San Bernardino.

Following graduation, she worked at various California pet clinics and hospitals before returning to Hawaii in 2006 to join the state Department of Agriculture as veterinary medical officer at the Halawa facility in Aiea.

Odani is co-author of a number of pathological research reports that are published in national and international trade journals. She also lectures at colleges, conferences, and symposiums in California and Hawaii.

Her expertise ranges from fishes to mammals, such as horses and cattle.

“I was in Alaska for two years (2000-02) as assistant pathologist at Prince William Sound, studying herring disease,” Odani says. “I performed necropsies of hundreds of Pacific herring to quantify the volume of toxins in their liver.”

OK, don’t suddenly leave the room. Veterinary pathologists talk about the liver, heart, stomach and other organs like it’s party patter. It’s what they do.

If you haven’t figured it out by now, the good doctor is kind of a CSI for animals. Although the animals are not dissected for crime scene investigations, there is detective work on causes of diseases and possible threats to humans or other animals.

For the state Department of Agriculture, this is an important part of preventing infectious diseases among commercial livestock and ensuring public safety from migrant species to the Islands.

The modern Veterinary Laboratory in Halawa is comprissed of a highly qualified staff, including Odani as veterinary pathologist, as well as an epidemiologist, chemist, microbiologists and a laboratory aide.

The pathology functions performed by Odani are primarily diagnostic to identify, prevent or manage pathogenic (germs) diseases related to farming.

“In order to import domestic animals, such as cattle, horses, goats, swine and poultry, they must be tested for certain diseases,” Odani explains.

Blood samples are collected from animals and tested for the presence of antibodies against a specific disease agent. Horses must be free from equine infectious anemia. Cattle must be free of anaplasmosis, brucellosis and bluetongue.

(Are you still with us?)

Pigs are tested for brucellosis and pseudorabies.

“We are fortunate in Hawaii to not have rabies,” Odani states. “It is important that we maintain that status. The introduction of rabies would have dire consequences, not only for public health, but it could adversely affect Hawaii’s unique ecosystem, tourism and our lifestyle.”

Thanks to the State-Federal Cooperative animal health program, Hawaii can claim it is also brucellosis-free and bovine tuberculosis-free. Brucellosis, a highly contagious condition caused by the ingestion of unsterilized milk or meat from infected animals, was eradicated 30 years ago.

To maintain this shield of prevention and outbreak among animals, there is constant testing and screening of livestock in the state. Points of entry, such as the airport and shipping docks, are monitored carefully.

Should there be concerns, these are usually brought to the department’s attention by local veterinarians and livestock producers. The work of Odani and other staffers attempts to address the causes of animal loss or death, so solutions can be addressed.

“It’s putting pieces together in a story that makes sense,” the vet says. “What we can see with the naked eye must correspond to what we see under the microscope.

“Right now, I’m dealing with pigs that have pneumonia,” she says, while examining a slab of pink animal tissue. “I’m looking at the lungs to see if there is evidence of viral or bacterial infection. A vet waits for the analysis, so treatment can be determined.

“The loss of one animal is concern enough. To lose an entire herd would be devastating to a rancher,” she adds.

We wondered if this delicate 4-foot-9-inch woman, who slings animal flesh like a meat packer, has any interests outside of examining dead animals.

She practices karate with her karate master-attorney husband Norman and 7-year-old son Nicholas. The Odani household also includes a pet dog, two cats and six clown loach fishes.

Does she ever discuss her work with the family at the dinner table?

“I’m asked not to,” she laughs.

Does her son aspire to Mom’s unique profession?

“He wants to work with live animals,” Odani answers.

For others seeking a career in veterinary pathology, Odani stresses the importance of competence in math and science as well as training in biological or animal sciences.

“There is a great need for pathologists in the bio-research field,” she says. “As long as there is (livestock) farming in the agricultural community, there will be a need for qualified veterinarians and veterinary pathologists.

“Advances in technology and the development of better diagnostic tools have taken necropsy to new heights. Although livestock farming in Hawaii has dwindled over the years, there still is a need to protect our vested interests in healthy animals and better farm management practices.”

So the next time you hear the word “necropsy” in a conversation, perk up and claim you know all about it because pros like Jenee Odani are maintaining the high standards of that profession.

NOTE: No animals were harmed in the writing of this story.