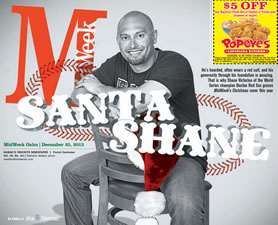

Santa Shane

Shane Victorino eats, sleeps and dreams of baseball. So much so that, to this day, he has never surfed, which makes him an oddity of sorts among those he grew up with.

No matter. Things have worked out.

But after a day of consecutive interviews and speeches, the Boston Red Sox right fielder had enough. Baseball drives the Maui native, but even the biggest Eagle Scout grows tired of giving the same answers to the same questions for hours on end. Therefore, it wasn’t a surprise that by the time MidWeek had gotten ahold of him, he was spent.

mw-cover-122513-shanevictorino-2

That is, until the questions turned toward his foundation.

Suddenly, the two-time World Series champion perked up. His eyes brightened and the smile returned. No matter what Victorino accomplishes in baseball, in his mind it will never top what he has done outside the game. The thousands of recipients of his largesse in Las Vegas, Philadelphia, Boston and, of course, Hawaii would likely agree.

The Shane Victorino Foundation was founded in 2010 to fulfill his long-awaited desire to give back to the communities that have supported him.

Helped by friends in Hawaii and elsewhere, the foundation literally has touched thousands of lives. For his charitable good deeds, Victorino received the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award in 2008 and the Branch Rickey Award in 2011. All-Star appearances are nice, but being recognized for things off the diamond are what really brings satisfaction.

“I look at the Boys and Girls Club in Philly that bears my name – those are the things that last forever,” says Victorino, whose $1 million pledge saved the 105-year-old club from closing. “When you’re done playing, someone else is going to take your position, someone else is going to be the next great baseball player who everyone will fall in love with. But for me to know that, in Philly, where I have that Boys and Girls Club, coming back here being involved in Waipio Little League, and what I want to do on Maui … that’s the kind of stuff that is so much more important.”

Diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as a child, Victorino struggled with his energy and emotions while growing up. Sports, medication and counseling have helped him control the disorder, which on rare occasions still flares up. It also may explain why he plays the game so hard.

Everything he does is all out.

“The Shane you see on the field is the Shane you’ll see off the field with the foundation,” laughs Kari Uyehara, the foundation’s executive director. “That’s how he operates. It’s 150 percent at all times.”

Although Victorino sets the tone for the foundation and is always in touch with the details, he’s allowed his staff and board members to use their own expertise to reach those goals. And why not?

He’s got some heavyweights helping him out. In Hawaii, that includes Keith Amemiya, senior vice president of Island Holding Inc.; Bank of Hawaii president and CEO Peter Ho; and BJ Kobayashi, managing partner and co-founder of BlackSand Capital.

Amemiya, who got to know Victorino while serving as executive director of the Hawaii High School Athletic Association, says the reason he got involved is not because what Victorino does (a MLB player), but who he is.

“He is a great role model for Hawaii’s youth,” he said.

“What impresses me is that Shane has been to able to be so successful on the national stage yet maintain his local roots and values. Which is why I think he’s been so successful.”

Amemiya says their shared philosophy of giving back to the community and never forgetting your roots not only links the two but is shared by all the board members.

Victorino’s journey to becoming a successful philanthropist began with his parents. With little extra money to hand out, both parents worked multiple jobs. Mike and Joycelyn Victorino gave what they had: their time. Whether it was something as official as Mike’s duties as the Hawaii state deputy for the Knights of Columbus, or efforts less formal like PTA meetings, early morning church cleanups or coaching a group of kids who had no one else, these were the examples he took from his biggest mentors.

“My parents didn’t have the financial ability to fund things, but they gave their heart, they gave their soul,” he says. “I look at my parents and how hard they had to work. They are my inspiration.”

Victorino’s success as a fundraiser is in large part because of his relationship with fans. He plays in a way that fans in get-tough-or-get-out sports towns like Philadelphia and Boston adore and demand. Victorino has had a Hawaiian-themed Father’ Day celebration held in his honor, and has been named to two All-Star teams. For one, in 2009, he received a record-setting 15 million votes by special fan selection. He has his own bobblehead doll. His grand slam against Detroit in the American League Championship made him an instant Boston legend, and a fan paid $3,750 in a charity auction for his playoff beard. Most important, when he has asked the community for money, it has responded.

“I’ve been blessed to be part of great communities that have shown support of my foundation,” he says. “At the end of the day, that’s what makes it special.”

The nation instantly was exposed to that special feeling of community in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing. The actions of normal citizens saved lives and helped police capture and kill a suspect. Their efforts also were felt by those at nearby Fenway Park, which quickly was turned into a memorial for the fallen and a place to celebrate the survivors.

“Sometimes I think back, I get speechless,” says Victorino. “When I take the field every night and I look up on that left field wall, the green monster, and I see that V Strong sign, it motivates me and tells me how fortunate I am to play the game I love. That V Strong sign stood for a city that is strong, is resilient and stood for all the victims who were devastated.”

Victorino has no definite plans for life beyond baseball. At 33, he still has a few years of productivity remaining, and perhaps a few more as a valuable role player. Two things are for certain: His eventual retirement will be someone else’s decision, and that no matter where he lives, the keiki o ka aina always will be closest to his heart.

“I am focused on Maui because that is where I was born and raised, and where I call home. I want to make fields; I want to make things as good as I can. But I can’t fix the world. I am going to tackle as much as I can, and having the support of the community helps me to be able to do these things.”