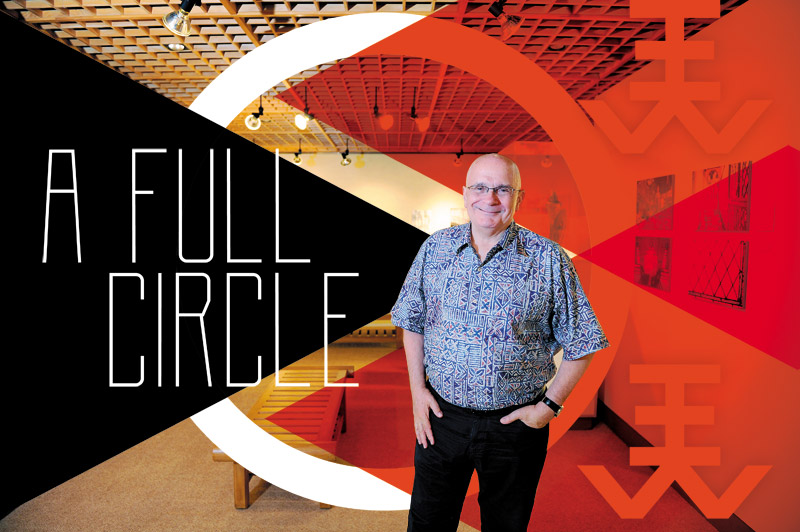

A Full Circle

Richard Vuylsteke was a research assistant at the East-West Center during his days as a graduate student at UH. Now, some 30 years later, he’s returned to lead the Center into a new era.

When Richard Vuylsteke arrived at the East-West Center to begin his new job as president, he garnered a bit of attention for the haste at which he moved into the position. He landed in Hawai‘i from Hong Kong on Dec. 30, 2016, and insisted on starting the job by Jan. 1, 2017.

Otherwise, he explains, “You lose momentum.”

And if anybody knows a thing or two about maintaining momentum, it’s Vuylsteke. Throughout his career, Vuylsteke has constantly been on the move. He’s had a varied career that spans industries — including the military, academia and journalism — and most recently was president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong. But his appointment at the East-West Center is something of a full circle — Vuylsteke was a research assistant there during his time as a graduate student at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in the 1970s and 1980s.

“I have a great love for the East-West Center, and Hawai‘i itself, and it is a chance to pay it forward,” Vuylsteke says. “I took a lot from this place. Maybe it is time to give back a bit.”

Vuylsteke grew up in Illinois and spent a year in India as a Fulbright scholar and three years in the Army before coming to University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa as an East-West Center scholarship recipient for graduate studies in Western and Chinese political philosophy. For him, it was a time of idyllic intellectual exploration — long conversations with visiting poets, working side-by-side with students who went on to be international politicians, and gaining “extraordinary exposure” to renowned academics and professionals who were affiliated with the Center.

The constant intellectual buzz allowed him to dabble in various areas of interest.

Richard Vuylsteke discusses his vision for the East-West Center.

“Everywhere I looked, I was just kind of a Velcro person — this would stick to me, that would stick to me, and I would find it really interesting,” he says.

And, as he points out, it has remained that way throughout much of his career.

After earning an M.A. and a Ph.D. from UH, Vuylsteke was hired as assistant director of local foreign policy research institute Pacific Forum. He’d been a teaching assistant throughout graduate school, and continued to teach classes at UH, Chaminade and Honolulu Community College. In the mid-1980s, he became the area studies coordinator for Chinese language students for the U.S. Department of State Foreign Service Institute. Meanwhile, he also taught English at National Taiwan University and was the editor of a national magazine in Taiwan covering social, political and cultural issues.

In 1999, he became president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei, and later, the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong. Throughout his tenure at the chambers, Vuylsteke oversaw committees in fields including finance, transportation, communications and more, while running conferences and delegations for a range of sectors.

“I’m a generalist at heart, I guess,” he says. “I’m curious.

The East-West Center sits on a 21-acre campus adjacent to UH Manoa.

GREG KNUDSEN PHOTO

“Or I can’t hold a job,” he jokes. “After a while, somebody would call up and say you’re kind of weird, you’ve got all these different areas in which you work, would you like to try this?”

It was one of those ‘want-to-try-this?’ phone calls that brought him back to EWC — and moreover, it was his own memories of the Center that prompted him to make the move.

The way that Vuylsteke sees it, EWC is really in the service industry — its service being “trying to help people do things better and more intelligently.”

The idea for EWC first took root in the late 1950s, when UH acting dean of arts and sciences Murray Turnbull proposed that the university create a space to be “a unique world center of higher learning where students of all beliefs, races and countries might meet … for serious study and interchange of those ideas which concern all men.”

The idea gained support from then-Sen. Lyndon Johnson, and the U.S. Congress established the Center in 1960. As EWC office of external affairs director Karen Knudsen points out, the Center’s early days were times of high tension between the U.S. and Asia.

“The fact that we were able to forge those bonds at an early time was very important,” she says.

The Center hosts a range of events, including this women’s leadership forum.

PHOTO COURTESY EAST-WEST CENTER

With the goal of facilitating relationships and understanding between the U.S. and the Asia-Pacific region, EWC offers a myriad of educational programs tied into UH; conducts regional research on topics ranging from economic growth to the environment and publishes its findings; and hosts seminars that provide opportunities for dialogue.

At any given time, EWC is a flurry of activity. In 2016, EWC brought together young professionals from China, Japan, Korea and the U.S. for a leadership workshop, hosted President Obama to speak to Pacific island leaders, organized an empowerment workshop for women in the Marshall Islands and Micronesia, published more than 80 books, studies and policy briefs, and conducted a weekly seminar program for Congress staffers on U.S.-Asia policy issues.

Last year alone, the Center reached 14,000 people through its events, had 1,087 institutional partnerships in 79 countries, and had 4,075 participants from 97 countries and territories.

While all of those numbers certainly are impressive, the crux of the Center’s impacts seems to be a little more intangible.

It was an EWC scholarship that enabled Amefil Agbayani to attend UH as a graduate student from the Philippines in the 1960s. Not only did that finance her education, but the environment at EWC shaped her career path.

“My EWC student experience was life-changing,” Agbayani says.

“I attribute my professional work in student diversity and my community work in civil rights to my EWC student experience,” she adds.

Agbayani was one of the founders of Operation Manong at UH, which worked to support immigrant children in school, later expanding to help underserved groups pursue higher education. Agbayani went on to be assistant vice chancellor for student equity, excellence and diversity at UH, where she worked to recruit and support underserved and disadvantaged students.

A big part of her EWC experience, Agbayani recalls, was simply being there at the Center — living in the residence halls and befriending people from other countries.

The importance of something so seemingly simple is a sentiment that Knudsen echoes.

“For those who come to the East-West Center and live in our dormitories … when you’ve shared a meal with someone, when you’ve stayed up at night talking issues with someone … it’s hard to go back and hate that person,” Knudsen says.

Take, for instance, an exchange program that the Center put on for journalists from India and Pakistan. Later, after the program wrapped, tensions were ramping up between the two countries. But, despite the animosity, the program alumni sought to work together.

“That was pretty amazing given the relationship between those two countries,” Knudsen says. “Our alumni were emailing (each other), ‘What can we do to help diffuse this?’ The fact that they keep those communications open, I think that is one of the most powerful things.”

When Vuylsteke first came on board at EWC, his initial action was, well, to not take action at all — he wanted to spend time listening to what people wanted from the Center. He spent weeks asking EWC employees and stake-holders what he likes to call his magic-wand question: If you had a magic wand, what is the one thing you would change about EWC?

“It makes my decision-making much easier in a sense, about what kind of priorities I should address at the East-West Center,” he explains.

Now, he is in the process of working to implement some of what that questioning period unveiled: developing more diverse funding sources, improving communications and marketing to promote the work that it does, upgrading IT and finding new ways to involve the local community.

As for his own magic-wand dreams, Vuylsteke has some big ideas. Addressing issues facing Pacific fisheries, and increasing Honolulu’s “smart city” capabilities by using technology to streamline services are just a couple of the things that he’d like to do.

But for all of those sweeping goals, the way Vuylsteke envisions tackling them seems to be fairly simple: by fostering the type of environment that he’d had as a student — the one that had allowed him to flourish in an international career.

“I think the East-West Center should be known for producing the kind of talent that people need globally, really,” he says. “In today’s world, the key talent that people are looking for … have cross-national, cross-cultural skills because it’s an international place, but also, they need to be working across sectors so that you can deal with the vocabulary and cultural differences between the military and business, academia and the media. The people that can do this are catalyst people. They are the ones that come into a room with all of these disparate people and they can work the room and take the lead on things and get things done.

“I had a 30-year career in Asia that was really facilitated by this place, so it is nice to be back, to maybe make sure it continues its good reputation and maybe build upon it.”

For more information, visit eastwestcenter.org.