The Plight Of The Mountain People

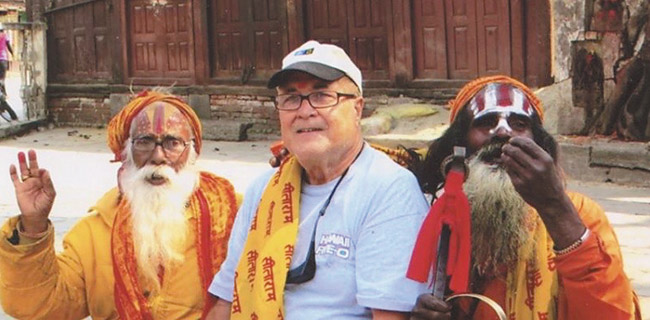

The author with two Nepalese holy men in Kathmandu. Some are predicting an asteroid will strike Earth Sept. 24 PHOTO FROM BOB JONES

My daughter Brett Jones, a State Department foreign service officer, worked out of the U.S. Embassy in Kathmandu until last year, designing plans for saving lives during a big earthquake. She always said, “It’s not about if, it’s about when and how big.”

She even had experimented with small drones as potential lifesavers. Everyone there knew when a big one hit there would be few open roadways to get people water, food and medical supplies.

Kathmandu is a warren of narrow alleyways with badly constructed buildings and very little engineering oversight.

It’s a magical place that I’ve gotten to know well during my visits, but it’s a political and economic basket case — 145th of 187 countries on the UN Human Development Index chart.

In 2001, the heir to the throne, Prince Dipendra, shot and killed nine members of his family, including King Birendra and Queen Aishwarya — and himself.

That led to a parliamentary republic. Self-governance turned out to be a nightmare. It’s been seven years and still no constitution — just fistfights in the Assembly, in which the two Communist parties have the most seats.

No surprise, the government found itself near paralyzed when it was most needed after the quakes.

Longtime Nepal journalist Thomas Bell observes that the country’s politicians perform a “farce of shameless, naked greed and short-sighted incompetence.”

We Westerners love the place for its scenery, from high mountains on its Tibet border in the north to the jungles on its India border in the south. Fabulous animal parks. Cheap stays. Welcoming people.

But for most of its 28 million citizens, it’s life at the very bottom of the economic scale. It’s not unusual for a villager to have to walk five miles to get to a road for a passing bus and a many-hours ride to a town. Roads are horrible and very dangerous, and repairs usually are done by a handful of men with shovels and wheelbarrows.

We who stay in the Yak & Yeti Hotel or who trek or helicopter to Everest see only a sliver of the poverty and difficult lifestyle. Everest climbers pay $60,000 to $100,000 for that thrill. The Sherpas who guide them and carry their gear get $125 per climb.

Nepal has to dance to a tune that satisfies China and India. It cannot survive without China’s money in return for making life difficult for Tibetan refugees, and the infrastructure help it gets from India in exchange for exporting hydro-electric energy.

There’s tourism — or was, until a week and a half ago.

There are at least 80 ethnic groups with their own languages. Communities are spread through tough mountain country with built-in ethnic antagonisms. It’s a culture of corruption and caste prejudice, a mix of uncomplimentary religious practices and very limited manufacturing, so little to export. It has an under-educated workforce.

There’s a large photo exhibit about the mountain people of Nepal at the East-West Center Gallery. It ends Sunday. This would be a most appropriate week to see it.

banyantreehouse@gmail.com