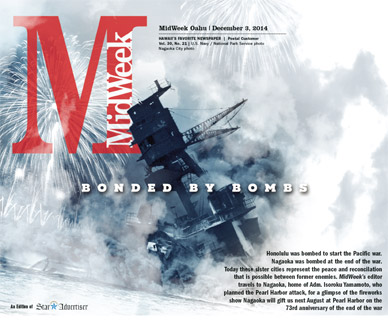

Bonded By Bombs

Honolulu was bombed to start the Pacific war. Nagaoka was bombed at the end of the war. Today these sister cities represent the peace and reconciliation that is possible between former enemies. MidWeek‘s editor travels to Nagaoka, home of Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, who planned the Pearl Harbor attack, for a glimpse of the fireworks show Nagaoka will gift us next August at Pearl Harbor on the 70th anniversary of the end of the war

This is a story about peace and reconciliation — because there has to be sooner or later, though that is certainly not the norm everywhere in the world today, if you pay the briefest attention to headlines. But as goals go, it’s not bad.

It also is a story about why next Aug. 15 at Pearl Harbor the Japanese town of Nagaoka, on the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, will gift its sister city Honolulu with the most incredible fireworks display we have ever seen.

Which explains why this past August I traveled to Nagaoka, hometown of Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, the man who reluctantly planned the infamous Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor.

This is a story with quite a backstory.

Honolulu’s sister city relationship with Nagaoka is based on death and destruction. We were bombed to start what would come to be known as the Pacific war, they were bombed at the end. Hard to say which was more horrific.

One of the questions I had traveling to Nagaoka involved why it was firebombed by U.S. warplanes on the night of Aug. 1, 1945 — just five days prior to the atomic bomb falling on Hiroshima. Was it retaliation for it being the hometown of Adm. Yamamoto? Or was it for some strategic reason, Nagaoka sitting astride the Shinano River, Japan’s longest?

It turns out neither.

In fact, there was a list — a deathly hit list — and each night (weather permitting) for months a different Japanese town was firebombed by U.S. planes. And the firebombing was quite efficient. In the Utah desert, the U.S. military simulated Japanese towns — constructed largely of wood, bamboo and paper, and built close together — to test the best method to incinerate them. A video put together by Takashi Hoshi at Nagaoka War Remembrance Museum shows how, for two hours, B-29 Flying Fortress bombers dropped thousands of rectangular metal canisters containing napalm (jellied petroleum) and trailing oil-soaked cotton tails. They easily penetrated roofs and on impact instantly burst into flames. At the museum I saw a mockup of blocks of charred streets, saw photos of stunned survivors the next morning finding 80 percent of their town destroyed, and read a first-person account from a young mother who ran through the burning streets with her infant daughter on her back and dived into a river, but it too was aflame, and at last realized her daughter’s cries had forever ceased. That night at least 1,460 people were killed in Nagaoka and 60,000 homes destroyed.

In all, by one calculation, the U.S. firebombing campaign destroyed 180 square miles of 67 cities, killed more than 300,000 people (the majority elderly, women and children) and injured an additional 400,000 — not counting the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 66,000 and 29,000 dead, respectively. If Japan had not surrendered after those attacks, Niigata, Nagaoka’s neighbor, and Kokura were next on the A-bomb list.

So: Coming directly from the War Remembrance Museum, traveling with Honolulu’s official sister-city delegation, we took a small bus straight to a downtown Nagaoka intersection, where chairs and a microphone had been set up on a red carpet, the Nagaoka Firefighters Marching Band standing by as crowds gathered on all corners. What, I wondered, would the band play? Soon Nagaoka Mayor Tamio Mori, a driving force behind the Honolulu-Nagaoka sister-city relationship, and Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell, who is equally enthusiastic, arrived waving in convertibles, and each made remarks about the importance of the Honolulu-Nagaoka sister-cities pact that began in March 2012.

“If our children grow up as friends,” Mayor Mori said of the many youth exchange programs between the towns, “they will not go to war.”

It was then the band broke into the opening notes of … The Star-Spangled Banner. And the people of Nagaoka and those visiting for the fireworks responded by cheering and waving small American flags.

It is in that spirit of peace and reconciliation that MidWeek takes a new look at the man who long argued against war with the U.S., but as the loyal and patriotic commander in chief of the Japanese navy reluctantly planned the attack on Pearl Harbor 73 years ago — and who in death would be proven correct in his prediction of the ensuing war’s progression.

There are times among nations and cultures when some people, for whatever reason — whether it is something lacking in their lives, misbegotten machismo, political paranoia, false patriotism or lack of a soul, whatever — make war seem the only solution to a perceived problem. In fact, the preferred solution. War will be good for us!

Such thinking led the U.S. into multiple and seemingly endless Middle Eastern wars. In the wake of the Republican power surge in elections last month, the war chorus in Washington is in crescendo.

So it was in Japan in the decades leading up to Pearl Harbor. These men — especially in the politically powerful army — were the neocons of their time and place, many clamoring for war against the U.S., bragging about Japan’s “invincible fleet.”

Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, proud son of Nagaoka, was not among them.

“Remember how Spain’s much-vaunted ‘invincible armada’ was defeated by the English navy?” he wrote.

Some considered such comments “seditious.”

He actually was born Isoroku Takano — his first name given because his father Sadayoshi Takano was 55 at his son’s birth — April 4, 1884, in Nagaoka, Niigata prefecture. His father was a teacher who came from a samurai family. In fact, Isoroku’s father and two elder brothers were wounded in the

Boshin War of 1868-69, and ended up on the wrong side, fighting to defend the shogunate of Yoshinobu Tokugawa against imperial forces. Their victory would usher in the Meiji Restoration.

He graduated from the Japanese naval academy in 1904, and in the Russo-Japan War of 1904-05 lost the middle and index fingers of his left hand when a shell exploded, most likely from an overheated gun he was firing. In 1916, he was adopted by the Yamamoto family of Nagaoka — not uncommon in those days for a samurai family without a son.

He attended Harvard University and had two military postings to the U.S., where he was impressed with the country’s industrial capacity, especially Detroit’s manufacture of cars. He also toured the oil fields of Texas and Mexico, and was impressed with the output. “A navy runs on oil,” he was known to say. And Japan had an oil problem — the navy rationed it.

In 1934, he was sent to England as chief negotiator for the Japanese navy in preliminary discussions before the second London Naval Conference that sought to limit Japan to three warships for every five the U.S. and Britain floated — 3-5-5 — as opposed to the former 8-8-8 formula. This outraged many in Japan, and they were further inflamed when he wrote at the time, “At all costs Japan should avoid war with America.”

In 1940, much to Yamamoto’s dismay, Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, assuring mutual military cooperation. It also all but assured conflict with the U.S. Yamamoto wrote leading up to the signing: “Both Japan and America should seek every means to avoid a direct clash, and Japan should under no circumstances conclude an alliance with Germany.” In short, there was nothing in it for Japan. Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy were not riding to Japan’s aid. Japan, he understood, was merely a second front, a second ocean for America — a perfect diversion from Europe.

On another occasion he wrote about the nationalists: “They are preoccupied with the idea of war, without giving any thought to the nation’s resources.”

Such utterances made him very unpopular with many in politics and in the army — especially future prime minister Gen. Hideki Tojo — and even with a faction of the navy. Army police followed his every move, and there were death threats from radical nationalists.

On Sept. 1, 1939, after six years of shore duty, Yamamoto became commander of the joint fleet, in large part to get him out to sea and away from political and military foes who posed a physical threat to his well-being.

The same day, Germany declared war on Poland.

Personally, Yamamoto loved games of chance — poker, bridge, shogi, mahjong — and often mused that he should quit the navy and become a gambler in Monaco, which he’d visited quite successfully during his stay in London. He was so successful at roulette, it’s said he was barred from a casino there. Some have suggested his gambling nature may have led to both military victory and disaster.

Visiting Chicago, he took in an Iowa-Northwestern college football game and became an instant fan of the sport.

He was slight of stature, standing a slim 5-foot-3, and had delicate fingers (the eight that remained) that were compared to a pianist’s. (In Nagaoka I met his grandson Gentaro, who almost is the admiral’s physical double.) Still, he projected strength, confidence and intelligence, and it’s said younger sailors were drawn to his leadership.

Yamamoto didn’t drink alcohol, but had a sweet tooth and enjoyed fine cigars (he’d also gambled in Havana). And he enjoyed the company of geishas, one in particular with whom he had a decades-long relationship, Chiyoko Kawai. He was said to be generous in gift-giving to subordinates and even their wives and children.

His wife Reiko bore him four children, daughters Sumiko and Masako, and sons Yoshimasa and Tadao. But partly because of at-sea duties and partly because he enjoyed night life, and perhaps because Reiko was said to be strong-willed and argumentative, he was seldom home. On their 21st wedding anniversary, Aug. 31, 1939, the day before he became commander in chief, Reiko was away. Upon his death, Tadao asked navy officers at the funeral to tell him something about his father, for he knew little.

Yet he was a voluminous writer of letters and poetry, and quite good at calligraphy. His brushes are on display at the Adm. Yamamoto Museum in Nagaoka. Nagaoka was always home, and he is not the first person to have a kind of idealized notion about a home-town, its foods and old friends.

As a military man, Yamamoto early foresaw the future of naval warfare belonging to airplanes — he’d been posted to Washington in 1927 when Charles Lindbergh was first to fly the Atlantic — and in the 1930s headed the navy’s Aeronautics Department and pushed for faster, stronger planes, and better-trained pilots. The day of the battleship was over, he said, the future is aircraft carriers. Traditionalists derided such thinking, but he would again be proven correct — first at Pearl Harbor, later in the bombing of Japan by U.S. planes, and even in his own death.

As Japan rushed to war in the late 1930s, and sensing the inevitable, Yamamoto began to ponder how to lead that war as C-in-C of the navy. He did not believe Japan had the resources or manufacturing capacity for a prolonged war. By early 1940, he was thinking Japan’s only chance of victory was a 12- to 18-month war, possibly 24, that would end with the U.S. begging for a truce. And the only way to accomplish that was to knock out the U.S. Navy in Hawaii. Spies were employed.

But he was adamant it was not a sneak attack. A coded cable had arrived at the Japanese embassy in Washington, D.C., the evening of Dec. 6 containing Japan’s ultimatum, with an attack set for 30 minutes after the ultimatum was to be delivered. But the Japanese embassy staff didn’t come in until after 9 a.m. EST that Sunday. By the time it was translated and delivered to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, it was 2:15 p.m. in D.C. The attack on Pearl Harbor had started more than an hour before. It bothered Yamamoto until his last day that Americans — he’d enjoyed his time in the States — thought it was a sneak attack.

Curiously, after Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto and the Japanese leadership seemed unsure what to do next, the attack having been so stunningly successful. Some in Japan referred to “divine aid.”

And the question always remains as to why the attack did not include bombing fuel depots on Oahu. The war would have looked much different if U.S. ships didn’t have oil.

In any case, Midway a few months later was a disaster, the Japanese shocked at the U.S. Navy’s presence — and quick rebound from Pearl Harbor. Japanese ships that weren’t sunk at Midway fled, some limping.

By Dec. 8, 1942, Japan’s war dead numbered 14,802.

The U.S. cracked Japanese communication codes probably even before the war — there is conjecture Secretary Hull knew the ultimatum was coming and its contents before it was officially delivered. Certainly code breaking was accomplished by the early days of the war. That led to Japan’s Midway debacle.

On April 13, 1943, Yamamoto was in the South Pacific and decided he needed to go forward to encourage Japanese troops — the first time he had done so in the war. In fact, he’d spent the entire war (including Dec. 8, 1941) behind the lines in his command ship. (Eisenhower wasn’t on the front lines in Europe either.) So a radio message went out to all units, specifying his exact schedule on April 18, when he would depart and arrive at each station. Despite pleas from other officers to cancel the trip after such a detailed message was sent, Yamamoto declined, saying he had promised his men he would be there. Besides, he thought it impossible Americans could decipher Japanese codes.

Americans intercepted that message and, knowing he was a punctual man, were waiting.

Two land-based Type 1 attack planes, one carrying Yamamoto, and six Zero fighters for protection departed Rabaul, Papua New Guinea, at 6 a.m. on the 18th, right on time. About 90 minutes into the flight, off the coast of Bougainville, one of the planes spotted at least a dozen American P-38 Lightning fighters flying below them. A brief air fight ensued, with the Americans appearing to specifically target Yamamoto’s plane, such was the accuracy of their intelligence. Yamamoto’s plane was shot out of the sky and crashed in dense jungle. (The other plane crashed into the sea and three were rescued.)

Two days later, after an exhausting trek through the jungle, a rescue party located the crash site. All were dead. Yamamoto was still sitting in his seat, his left hand gripping a sword from Niigata given to him by his brother. He had been shot in the lower jaw, the bullet exiting near his temple. He was dead before the plane hit the ground.

Of the 12 men who left Rabaul, nine perished.

And so in death, Yamamoto was proven right. Japan could not win a protracted war against America. The warmongers were wrong. In fact, the Japanese military was ineffectual in stopping American bombers on their nightly incendiary runs. On the night of Aug. 1, 1945, 80 percent of Yamamoto’s beloved Nagaoka was destroyed, two weeks to the day before Emperor Hirohito would belatedly surrender.

The following year, to commemorate the bombing date, Nagaoka city fathers put on a fireworks show. The town, like a phoenix, was literally rising from the ashes. Each fireworks burst, in a Buddhist sense, was a prayer for the dead, and for peace and reconciliation. And they thought the fireworks might attract some tourists to boost the local economy.

They were right. I attended the first of two nights of fireworks, Aug. 2-3, and 530,000 people lined either side of the Shinano River — in a town with a population of about 250,000. A similar number attended the following night.

The two-hour show began with a single white chrysanthemum burst, then another — the first a prayer for Nagaoka’s dead of Aug. 1, 1945, the other for Hawaii’s dead of Dec. 7, 1941.

What followed was two hours of the most dazzling display I’ve ever seen, times 90, fireworks fountains sometimes filling a half mile or more of the sky. Unlike small shells used for fireworks off Waikiki, some of these shells were 2 and 3 feet in diameter, and the blasts were concussive — you feel it in your organs. The displays were so immense, they became intimate. Alas, for safety-in-transport reasons, the biggies will not be used when Nagaoka, at the behest of Mayor Mori, gifts Honolulu with a fireworks show at Pearl Harbor next August on the 70th anniversary of the emperor’s surrender. But it will be big.

It will begin with two white chrysanthemum bursts.

“We will,” says Mayor Mori, “come full circle.”

Somewhere, I believe, Isoroku Yamamoto will be pleased.

Research for this story includes numerous sources, but the most valuable by far is the biography The Reluctant Admiral: Yamamoto and the Imperial Navy by Hiroyuki Agawa (published by Kodansha International). The depth and breadth of Agawa’s own research is remarkable, his writing (and John Bester’s translation) clear and straightforward. It’s a good read filled with surprising detail after detail.

On another commercial note: Seeing the Nagaoka fireworks last August, like a great piece of art or music, improved my life. If you’re interested, JTB in Honolulu offers tour packages.