The School That Buell Built

Martin Buell, founder of Universal Kempo-Karate Schools Association, with wife Sheila, who serves as president.

Martial artist Martin Buell no longer does flying kicks, but the kempo and karate grandmaster sure knows how to inspire his students, both here and abroad, to reach for the sky and grapple with the impossible.

The aged and white-bearded martial arts expert who’s dressed in a black gi and wrapped in a purple-and-white belt is hurting — so much so that he can’t kneel nor can he stand for long periods of time without the use of crutches. No, the pain isn’t the result of previous duels with ninja assassins, warring monks or evil clansmen, but rather, his ongoing battle with the most persistent and dreaded of all foes:

Master Chronos, or that dude we simply call Old Father Time.

Multiple hip-replacement surgeries within the last two decades have made it as impossible for this combat practitioner to perform a roundhouse kick as it is for him to straddle an opponent and get into closed or open guard position — moves he once performed so effortlessly.

Yet despite his mobility challenges, kempo and karate grandmaster Martin Buell is never too sore to occupy his customary spot in the corner of a building in Pearl City. Like a wise but wounded warrior still willing to fight the good fight, he gently dispenses pearls of wisdom from a seated position to both adults and youngsters alike, who gladly come to his headquarters of knowledge and discipline, Universal Kempo-Karate Schools Association, to soak up Buell’s self-defense techniques and his philosophy of life, which includes one of his favorite dictums: “Nothing is impossible.”

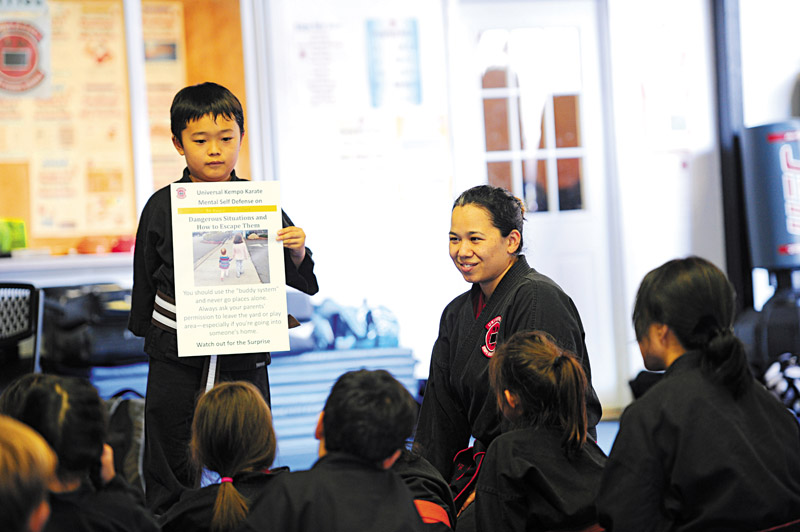

Students listen to a message on the “buddy system” as Justin Sukita holds up a poster with instructor Ku’ulei Nitta on the side.

Because of his physical limitations, Buell relies on senior instructors to handle the demands his body can no longer perform within the school that he built. Thankfully, his ability to educate and inspire is still there; they were always among the greatest weapons at his disposal anyway.

“As long as I can teach, I’m fine,” says the man who turns 76 in less than two months. “My mind is still sharp. I know things backward and forward. And from where I sit, I can still see what needs to be corrected.”

Proof of his nimble noggin and all-seeing eye is found in his Stranger Danger lessons. Presented on placards at the beginning of each class, these tutorials seek to increase his younger students’ awareness of their surroundings and prepare them for the unexpected. Or, as Buell loves to say about the uppercut that life often throws at the unsuspecting, “You need to watch out for the surprise.”

Usually, he’ll ask young disciples — who range in age from 6 to 17 — to read from the placards and act out potentially hazardous scenarios in class. For some, this requires overcoming their fears of addressing a large group. For others, it means learning to take charge of a setting. “It’s all about developing confidence and leadership,” says Buell.

Instructor Pat Nitta with students (from left) Tayler Coloma, Jamie Sukita and Olivia Aquino practice “hold the form.”

Ultimately, Stranger Danger suggests that while knowing how to block, punch, kick and throw is good, understanding how to remain calm, think clearly and get out of perilous circumstances is much more important.

“Stranger Danger is mental self-defense,” Buell says. “Danger has no face; it could be anyone. But through these lessons, we teach our kids how to escape from dangerous situations. What happens, for example, if you’re ever cornered in an elevator? Or, what do you do if a stranger offers you candy?

“For years and years, I’ve been teaching children about life and how they should live to be safe in this world. To live life, you gotta be aware — like an animal at a water-hole,” he continues. “If you’re not aware, there are predators around you all the time, and they’re ready to pounce.

“So when danger comes, you have to be able to move — you gotta be quick.”

One of his favorite Stranger Danger lessons encourages use of the buddy system so that students never find themselves alone. Buell says the system began decades ago following the death of Joe Emperado — the younger brother of kajukenbo founder Adriano Emperado.

Coby Chhy (left) and Justin Sukita (right) practice knee technique as instructor Cory Takemoto observes.

In 1958, Joe worked as a bouncer in a Honolulu bar called The Pink Elephant. One evening, he was knifed during a brawl with a group of troublemakers; the very next day, he succumbed to his wounds. His death led to a new custom among kajukenbo practitioners that required escorts to accompany higher-ranking martial artists wherever they went.

“With old-school kajukenbo style, nobody even went bathroom by themselves. It was always with somebody else,” explains Buell. “It’s the same when someone would leave your house. You’d stay by the door until that person was in the car and drove away safely.”

The second of three boys born in Honolulu to Irish-Chinese parents Joseph and Daisy Buell, the grandmaster spent his early years moving between quonset huts located next to Camp Smith and low-income housing in Pālolo Valley. His father was a lawyer who lost his license and turned to alcohol, only to die at age 55. Thereafter, making ends meet became a daily worry for his mom.

“But we learned to survive on the streets,” Buell recalls. “And even if we wasn’t living in a housing project, I would still spend a lot of time there. Every housing project there was in Honolulu, I was there, just hanging around.”

Shortly after turning 11, Buell started taking kenpo (he would change the schools’ spelling to “kempo” in 1974) at Central YMCA. Later, he moved to nearby Kaimukī YMCA for judo and kajukenbo lessons.

For Buell, the fighting disciplines were attractive because they gave his life stability and meaning. “I was a wild kid,” he confesses, “and street fighting was common back then. We’d go out and sometimes there would be three fights a night. Before, it was like you lick me, well then I’ll put two on you. And if you bring two, then I’ll bring four. That was the game.

“But when I got into martial arts, there was discipline, and I liked the zen aspects of it.”

Eventually, he began teaching the eclectic art of Chinese Kempo-Karate (a combination of karate, judo, jiu-jitsu and boxing) after receiving his black belt from Walter Godin of Godin’s School of Self-Defense. Buell opened his first school at Pacific Palisades Community Center and later welcomed students to a branch at Highlands Intermediate School. That remained his base of operations until about eight years ago, when he moved to his present location on Kuahao Place in Pearl City.

During the late 1960s and throughout the ’70s, he also competed in his share of full-contact tournaments. “But I got disqualified a lot,” Buell remembers, chuckling. “I don’t know — I guess I was too aggressive.”

From that point forward, some of his students turned senior instructors began launching new branches, both here and abroad, and in 1981, Universal Kempo-Karate Schools Association was officially born, with Buell’s wife, Sheila, serving as president.

Today, the school’s founder and 11th-degree grandmaster estimates he has “around 500 students” throughout Hawai‘i — with satellite schools in Kalihi, Mililani, Waipahu, Kapolei and Kāne‘ohe on O‘ahu, and Kea‘au and Waimea on the Big Island, to name a few — and “close to 3,000 students” throughout the continental U.S. and Barbados, West Indies.

“In my life, I’ve taught full-contact fighters, mixed martial artists, military people — I did everything,” says Buell, whose celebrity pupils include local comedians Augie T and Kaui Hill, aka Bu La ‘Ia. “But I’ve come to realize that the innocent needs this more than anyone else.”

Which explains why his heart remains with the children. It’s also why he doesn’t like turning away any youngster from his classes and depriving them of a martial arts education.

“I have some students with special needs. Others are real shy or aren’t quite as rugged as others,” says Buell, who also offers weekly classes to adults. “But I’ll always give them a chance to hatch, as long as they can follow along and they aren’t a danger to anyone else.

“Plus, I’m lucky because we have compassionate instructors who enjoy guiding these children.”

That compassion, though, begins with him and is most evident in how he treats students who come from challenging financial circumstances. Through his Universal Foundation, which raises money through private donations, school fundraisers and sales of his martial arts instructional DVDs (generally purchased by his teachers around the world), he is able to defray some of the costs associated with the students’ tuition.

“We do what we can to help,” explains Buell, a retired marine machinist who worked at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard. “Like the DVDs: I don’t get rich off of them. Whatever money is made goes right to the foundation.”

Buell’s positive influence is not lost on his pupils.

“At first, I thought kempo was all about fighting,” says student Noah Gayagas, 10. “But after coming here, I’ve learned it’s mostly about life and treating each other well.”

Another 10-year-old, Taiko Tyau, credits the school for teaching him self-defense and self-discipline.

“If a stranger came up to me, I wouldn’t know what to do if I didn’t know kempo and karate,” says Tyau, who’s been training with Buell for about four years. “But because I know, I have a better chance of getting out of the situation.”

Just as importantly, Buell has taught youngsters like Tyau to dream the seemingly impossible, for when asked what he hopes to eventually earn through the study of martial arts, a grinning Tyau glances at his aged martial arts grandmaster sporting a purple-and-white belt, and, in a voice chock-full of confidence, confesses, “his belt.”