Man On A Mission

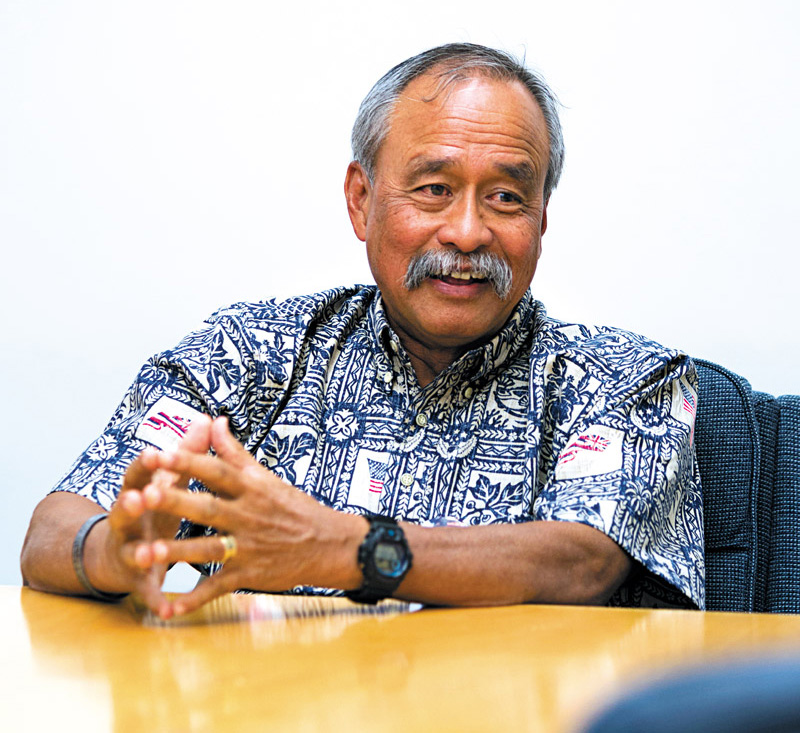

Allen Hoe stands in front of the Mana O Ke Koa display, where his picture will be placed.

This week, U.S. Army Gen. Robert Brown will present Vietnam veteran Allen Hoe with the Mana O Ke Koa award, which honors Hoe for his dutiful service to soldiers, civilians and families of the U.S. Army Pacific.

The days leading up to Mother’s Day 1968 coursed without much fanfare. In fact, things were so quiet that Spc. 5th Class Allen Hoe, who was serving in Vietnam as a combat medic with the U.S. Army’s 196th Light Infantry Brigade and 2nd Battalion 1st Infantry Regiment, wasn’t with his team at the time. Hoe had hung back at headquarters to get some work done.

Within 48 hours, however, everything changed. Early on that fateful morning, his team was overrun.

“I lost 18 of my men,” Hoe quietly recalls.

That moment changed his life forever, setting in motion a commitment to working with veterans that continues to this day. He is a civilian aid to the secretary of the U.S. Army, for example, working as a liaison of sorts between that branch of the military and its presence here in Hawai‘i. Hoe also is president of the foundation of the “United by Sacrifice” memorial at Schofield Barracks, and is a board member of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. — and that merely scratches the surface of all Hoe has a hand in.

Hoe will receive the annual award from U.S. Army Gen. Robert Brown.

For his efforts, U.S. Army Gen. Robert Brown will honor Hoe this week with the Mana O Ke Koa award.

“The annual U.S. Army Pacific Mana O Ke Koa award — the Spirit of the Warrior — is our opportunity to honor those men and women who provide steadfast support to soldiers, families and the Army community,” Brown explains.

“Awardees demonstrate unparalleled patronage for and civilian leadership toward our Army,” he adds. “Allen Hoe embodies those qualities. While each nominee for the award is deserving, we feel Allen’s dedication to the Army is truly outstanding.”

For Hoe, it all goes back to Mother’s Day 1968.

“That was one of the things most critical in terms of what set me on this course to … not lose sight of my commitment to soldiers,” he says. “It started, really, with the families of those men that were killed that day, and those men today who are still missing in action from that battle.”

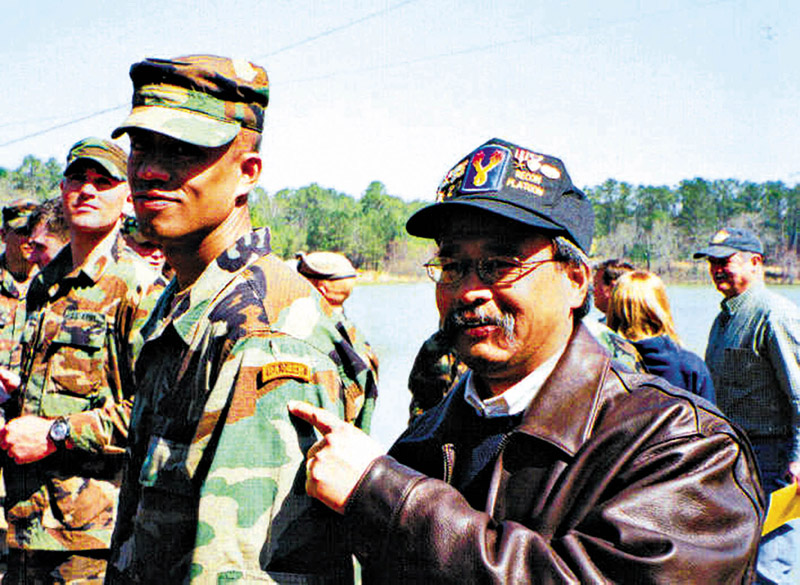

Allen Hoe beams as his son, 1st Lt. Nainoa, participates in his Ranger graduation ceremony at Fort Benning.

Hoe wasn’t always destined for war in Vietnam. After graduating from Hawaiian Mission Academy in 1965, he was drafted by Uncle Sam in the summer of ’66.

After completing training to become a combat medic, Hoe watched as many of his peers were shipped overseas. He, on the other hand, was sent to an artillery unit in San Francisco before getting stationed at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, California.

By all accounts, it was a fun and relatively easy gig. Hoe worked standard eight-hour weekdays, while weekends were spent exploring the Golden State with friends.

But there was something niggling at his mind. Guys were returning from Vietnam, sharing stories of war — and a 20-year-old Hoe was fascinated.

His dad had served in World War II, and Hoe had grown up listening to relatives regale with tales of his Native Hawaiian, Japanese and Chinese ancestors who fought as warriors. A couple in Europe were even troopers in Queen Victoria’s army, battling in the First Anglo-Afghan War.

“As a little child, I was impressed by that,” says Hoe.

So he volunteered to go to Vietnam.

His first application was rejected.

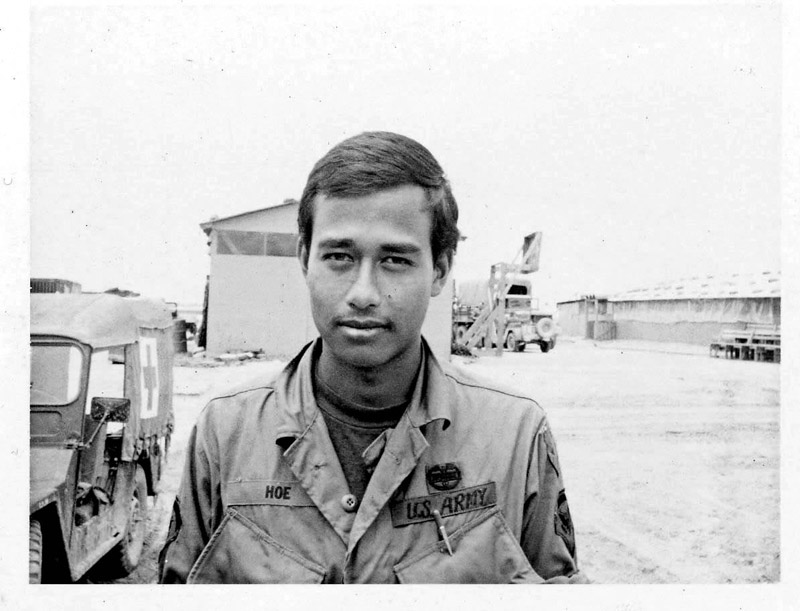

Hoe in Vietnam in 1968.

PHOTOS COURTESY ALLEN HOE

“Guys are dying over there,” Hoe remembers his sergeant telling him.

But Hoe was insistent. “At that time, it was kind of like, well, I don’t know what combat will be like or what it’s all about, but 30 years from now, I don’t want to kind of wonder how I would have done,” says Hoe.

His sergeant acquiesced, and Hoe’s second application was accepted soon after. It was Dec. 1, 1967, when he arrived in Vietnam.

Hoe eventually found his way into the long-range reconnaissance team, going incognito to inconspicuously search for enemy units. Fellow soldiers taught him how to handle weapons and communicate via radio, while Hoe shared advanced lifesaving skills in the event he was ever incapacitated.

As dangerous as it was, a still-young Hoe also found it to be pretty fun, too.

“Fun in a kind of a strange sense because you’re doing stuff that’s high-risk, and your survival really depended on your skills and the skills of the guys who are with you,” he adds.

But war is hardly all fun and games. The third time Hoe almost died, he and his team had been ambushed. While fellow soldiers engaged the enemy, Hoe climbed up a tree at the request of a lieutenant to see if he could spot where the gunfire was coming from.

The skills you learn practicing law — in terms of dealing with … bad people, good people, critical issues and how you can help to make other people’s lives better — that, to me, is just very rewarding.

ANTHONY CONSILLIO PHOTO

“All of a sudden, I hear this crack right over my head and tree bark starts falling down on me,” recalls Hoe. “The sniper had missed.”

Hoe spent 10 months in Vietnam, and then life, it seemed, picked up where it had left off.

He returned to school, completing his undergraduate degree in political science at Leeward Community College and University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. In 1973, the William S. Richardson School of Law welcomed its first class — Hoe among them.

A degree in law, Hoe felt, would be applicable in any career he ended up in. It just so happened that law stuck.

His first job was as a deputy corporate council for the City & County of Honolulu, representing the city on all personnel matters and working for the likes of civil service, and the fire and police departments.

Five years later, Hoe opened up a law firm with childhood friend John Waihe‘e. Even after Waihe‘e decided to “go play big-time politics,” as Hoe refers to it, he remained in practice, while also serving as a member and chairman of Hawai‘i State Ethics Commission, as well as a member of the Stadium Authority for Aloha Stadium.

Today, Hoe focuses his profession primarily on transactional law.

“It’s hard work, long hours,” says Hoe. “But at the end of the day, the skills that you learn earning that degree and the skills you learn practicing law — in terms of dealing with … bad people, good people, critical issues, important issues and how you can help to make other people’s lives better — that, to me, is just very rewarding.”

The ways in which Hoe continues to devote his time to veterans and military affairs are many. He doesn’t even list them all. After naming only a handful, he stops to add, “American Legion, and kind of all the various service organizations.”

In fact, it’s thanks to Brown that the enormity of Hoe’s contributions comes to light.

“He serves on multiple veterans and recognition memorial committees, such as the Vietnam Women’s Memorial (Project) and the (National) Native American Veterans Memorial, at both local and national levels,” says Brown. “He provides equestrian experiences to Wounded Warriors and their families … He serves as a career counselor and continuing education counselor for soldiers leaving active duty and transitioning to civilian life, and connects outside volunteers with Army units and troops that have needs they can’t meet on their own.

“And he speaks to young leaders, soldiers and civilian organizations about his experiences as both a combat medic and a Gold Star father to help tell the Army story and to build resiliency in our soldiers.”

When Hoe talks with soldiers, he tells them that there are two rules in war. First, death is a reality. Second, there’s nothing anyone can do to change rule No. 1 — a message that rang true on Jan. 22, 2005, when Hoe’s eldest son, Nainoa — a lieutenant in the Army in the 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment, 1st Stryker Brigade of the 25th Infantry Division — was killed in Mosul, Iraq.

“Having lived through my war and having been lucky, I got jaded, if you will, thinking that I could transfer my luck to my boys,” says Hoe.

It was in 2000 that Nainoa made it clear that he would be donning a uniform, just like his dad. Instead of applying for direct commission, he enlisted, earning both his master’s degree and commission in 2003.

Hoe recalls that his son loved life as an officer, Ranger, paratrooper and scuba diver. More than anything, though, Nainoa was a great leader.

“His experience and maturity made him stand out among his peers,” says Brown, who was Nainoa’s brigade commander during his 2004 and 2005 deployments to Iraq. “He was calm under pressure, a steady presence for others around him.

“No one cared about soldiers more than this servant leader,” he adds. “Nainoa was there, first and foremost, for his soldiers — never for himself — and his dedication to his team and his country was unquestionable.”

So in what may be Hoe’s most profound contribution to the military community here in Hawai‘i, he and his family participate in four special events each year to honor Nainoa. They include two scholarship giveaways — one to a third-year cadet in the ROTC battalion who also is enrolled in a master’s program, and one given on Nainoa’s birthday, Aug. 28, at the training center at Schofield Barracks named after him to a new cadet in the Army ROTC program — as well as a memorial service on the day of his death, and a presentation of the Mamakakaua O Mānoa Award recognizing the cadet deemed the best on Commissioning Day. (Mamakakaua, explains Hoe, was an elite warrior group that fought alongside Kamehameha. The award itself is a pahoa, an 18-inch dagger made with shark’s teeth, crafted by La‘akea Suganuma, a master weapons maker and grandson of Kawena Pukui.)

“Allen is an exceptional person,” says Jan Scruggs, a close friend of Hoe’s who founded the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. “He channeled his energies appropriately after the tragedy of the loss of his son to a sniper’s bullet in Iraq. He became involved with the U.S. Army to find ways to keep the memory of Nainoa Hoe alive. He is a loyal friend and a patriotic American to whom the nation and the people of Hawai‘i owe a great deal of appreciation.”

Despite all this and more — Hoe also was asked by then-U.S. Secretary of Veterans Affairs Anthony Principi to serve on a committee that would eventually bring to life the Vet Center Program — he still seems shocked to know he is receiving the Mana O Ke Koa award. Hoe can still recall Bill Paty (the two are close friends, who, along with two others, built Honolulu Polo Club in 1986) being honored as the first awardee.

In Hoe’s eyes, the award has always gone to those who have made significant contributions. “Me, I’m just another soldier,” Hoe says with a laugh.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, U.S. ARMY!

The U.S. Army will celebrate its 243rd anniversary on June 14 — which happens to be Flag Day, too.

According to Col. Christopher Garver, chief of public affairs for the U.S. Army Pacific, it all began on that date in 1775, when the Continental Congress ordered 10 rifle companies to be formed with volunteers from Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia.

“A phrase that we use is ‘Before there was a nation, there was an army,'” he says. (The Declaration of Independence, of course, didn’t exist until July 4, 1776.)

On this side of the nation, the Army has been in the Pacific for 120 years. To mark the occasion, it’s celebrating with Pacific Theater Army Week. Going on now, events include a couple of runs, concerts and much more. On Friday, June 15, Allen Hoe will be honored with the Mana O Ke Koa award during a lu –‘au celebration at Schofield Barracks.

For more information, find Pacific Theater Army Week on Facebook at facebook.com/pacifictheaterarmyweek.