Jon Kobayashi Talks New Athletics Revenue Streams

Jon Kobayashi, the man now heading Ahahui Koa Anuenue, the fundraising arm of UH Athletics, is a familiar face on Bishop Street, and he’s looking for support from there as well as from ‘Main Street.’ He’s also taking an aggressive approach in creating new revenue streams

Jon Kobayashi is a cunning deliverer of messages. The president of Ahahui Koa Anuenue — the fundraising arm of University of Hawaii Athletics — is well versed in the athletic and financial history of University of Hawaii. He also has had a front-row seat, as his father, Bert, a prominent attorney and booster, has helped determine the university’s future. Yet, when queried about the dark society that controls not just the university but also the entire state, the younger Kobayashi develops a sudden lack of knowledge.

“I don’t know what you are speaking of,” says the Punahou graduate, echoing the answer with a slight grin as he repeats the response to a battery of questions.

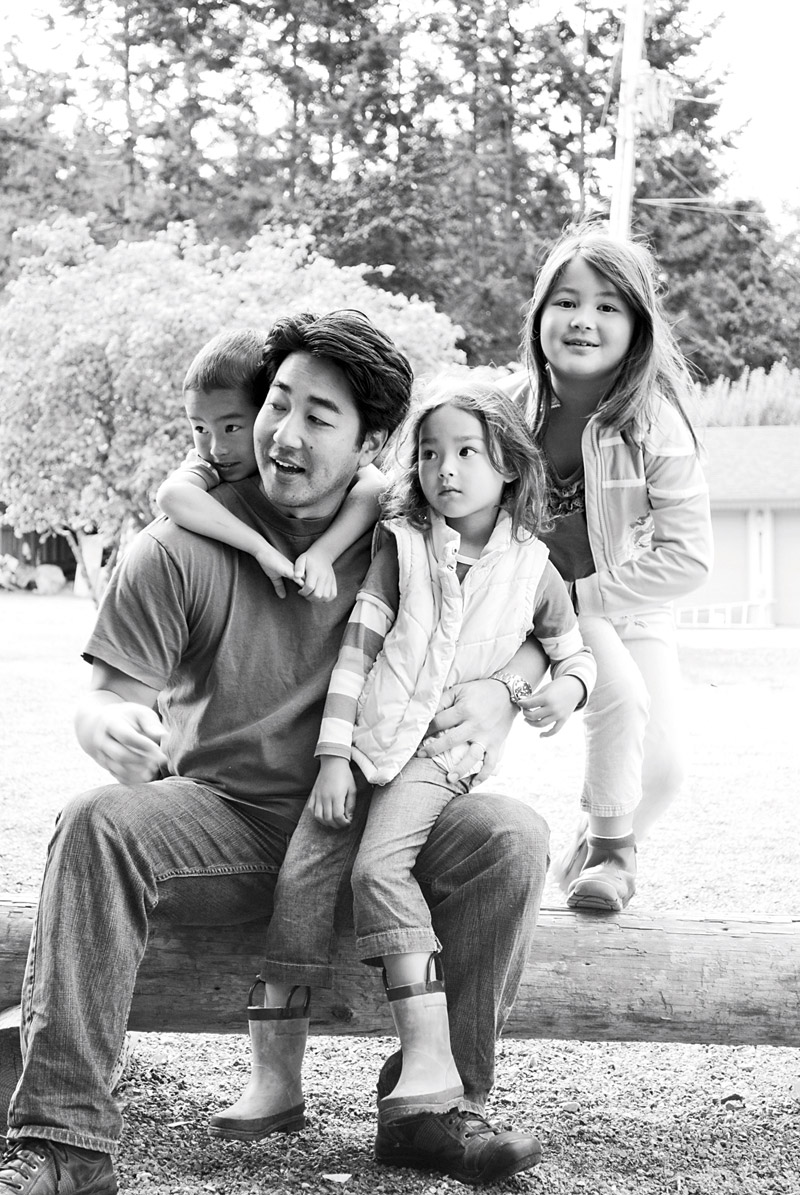

Jon Kobayashi, the man now heading Ahahui Koa Anuenue, the fundraising arm of UH Athletics, is a familiar face on Bishop Street, and he’s looking for support from there as well as from ‘Main Street.’ He’s also taking an aggressive approach in creating new revenue streams. PHOTO BY NATHALIE WALKER

Like Fight Club, the first rule of the Punahou Mafia is that there is no Punahou Mafia.

Regardless of surname and any assumed connections, the “recovering attorney” has been handed a difficult task. Faced with increased costs, lack of legislative help and growing customer indifference thanks largely to an underperforming athletic department, Kobayashi’s job is to fill the growing financial gap.

It’s a task that has stumped nearly everyone who has tried.

The university has been bleeding red ink, posting deficits for 12 of the past 14 years. Athletics director Dave Matlin said the debt could be as high as $4.4 million when the annual audit is concluded. Two years ago, the university forgave $13 million in athletic department debt, and for the first time UH will pay the full cost of attendance for athletes, which could add another $500,000 in annual operating costs.

Things aren’t good at the state’s flagship university.

Faced with such gloomy financial details, Kobayashi remains calm, if not excited by the challenges. Where most see problems, he sees opportunity in all those angry faces. Either he has a plan or he’s nuts.

“It is great when everyone loves you. When they hate you, at least there is energy there, and energy can be redirected,” he explains.

An amateur collector of local art from the 1950s and ’60s, the 47-year-old came to the job after running Outlook Inn & New Leaf Café in Eastsound, Washington — on Orcas Island. At one time, the hotel was home base for a bohemian bunch of truth-seekers who arrived to listen to owner Louis Gittner, a noted spiritualist and healer. Gittner was partners with Starr Farish, father of Kobayashi’s sister-in-law Sara Farish. By 2000, Gittner was out and Farish had turned over operation of the hotel to his children. The change in leadership didn’t make for a profitable business, and with his combined three summers of hospitality training — two setting up the breakfast buffet at Pacific Beach Hotel and one at the front desk — the owners tossed Kobayashi the keys and left.

“I was there three weeks, and one day people started walking into my office and said, ‘It’s payday today.’ And they just sort of stood there looking at me. I didn’t know I was handling payroll.”

It took some time, but he began figuring things out. He hired a new chef and built a team that shared a common vision. In time, profits doubled and sales nearly quadrupled, with very little spent on capital improvements.

“We tried to be very clear on who we were, how we got there and how we would react,” he says. “That helps everyone know what direction to move in.”

He’s trying to do the same with AKA by creating a sales and customer-service culture to replace the one that had focused on renewing existing commitments — and little else.

“AKA had no sales force, it had no sales competence. What we had was a renewal force and a renewal competence,” Kobayashi says. “Sitting back and waiting for the community to come in just doesn’t work anymore. We have to go out and bring the community back in and to nurture that sense of ownership and to really make an effort to say we need you, we want you and we appreciate you.”

The younger Kobayashi joined his father’s firm after graduating from University of Puget Sound. For 13 years he was a successful commercial litigation attorney, but the continued climb up the financial ladder began to have a negative effect. His oldest daughter Sofia was in preschool, and his wife, Adina Cunningham, had just returned to her own law career. The twins, Joshua and Sachiko, were at home with the nanny.

Jon Kobayashi at an Orcas Island oyster farm with children Joshua (now 9), Sachi (9) and Sophia (13)

KOBAYASHI FAMILY PHOTO

“We were working harder and harder to make more money to get better and better people to raise our kids,” he recalls with obvious discomfort. “It didn’t feel right.”

So when the hotel gig presented itself in 2007, he left the family business and began a great adventure. The experimental foray into the hospitality field was both a commercial and personal success. The hotel became profitable and their lifestyle was enviable.

They hiked and fished on the weekends. A shellfish farm was just 15 minutes away, and fresh crab, clams, oysters, salmon, cod and halibut were readily available. Apples and pears came from a nearby orchard, and life was synced with the seasons. They looked forward to tulips in spring and made apple butter in the fall. Sofia studied in a one-room schoolhouse and the bucolic life fit the energetic family.

Then they felt the tug to return home.

“The idea of my kids not being raised in Hawaii was needling me, and every time I saw my folks they seemed to get older faster.”

The timing was right. AKA was looking for a new leader after former president Vince Baldemor accepted the position of executive director of athletics at Hawaii Pacific University. Kobayashi had the name, and after building one small business, he felt he could do the same for another.

Kobayashi doesn’t deny that being the son of an influential community member has its advantages, but says whatever benefit he might have received ended once the interview began.

“Realistically, yes, it gets me to the front of the door, but that’s it,” he says. “People are going to hold me to a higher standard, maybe, because I am Bert’s kid. I just can’t be good, that’s what I feel.”

The junior Kobayashi came to the job burdened with several challenges, but has benefited from one major change. Two years ago, AKA became its own 501(c)(3) nonprofit, freeing itself from the often-suppressive rules of University of Hawaii Foundation, under which AKA operated since its inception in 1967. Kobayashi was its first employee and the change of status made possible new revenue streams. Two of the newest initiatives already showing growth are Coaches Choice and H Club.

Coaches Choice is a crowd-funding program that allows for the donation of funds to specific needs. Wahine Soccer coach Michele Nagamine was an early adopter and raised $10,553 for new soccer goals. New men’s basketball coach Eran Ganot raised $7,935 for a Gun 8000 basketball shooting machine, and Dave Shoji got more than $9,000 for a Saber Glide floor-cleaning machine. To date, Coaches Choice has generated more than $55,000 in mostly small-amount donations, and eight other coaches and trainers also have posted goals.

H Club is an updated model of traditional booster club programs. But whereas, in the past, membership was limited to a small number of set donation packages, H Club members now can purchase whatever level of benefits that interest them. Donors wishing for more perks no longer have to purchase a higher-level package but can reach other incentives by simply adding to their current donation level. Changing the way they do business and having the ability to customize booster programs is key to generating more interest and revenue, says Kobayashi.

“From a customer-service standpoint and a sales standpoint, they (donors) don’t want three times what others get, they want to get 100 percent of what others don’t get. We need to build inventory to make donations valuable and for donors to get a return on their investment.”

Such benefits may include valet parking at Stan Sheriff Center, reserved parking at Aloha Stadium, special seating areas, food and invitations to special meet-and-greets with players and coaches.

In addition to generating more revenue from ticket buyers and boosters, Kobayashi is looking to better monetize the athletic department facilities, something that wasn’t possible under its previous memorandum of understanding with UH Foundation. Venues such as Les Murakami Stadium, Stan Sheriff Center and Clarence T. C. Ching Field mostly sit empty in the offseason, generating no income for the university and athletic department.

Kobayashi says talks with those with the ability to make such deals happen are moving along.

“A big part is engaging Bishop Street and engaging Main Street while working with the athletic department and upper campus. It is a very unique ecosystem we have here,” he says.

Discussions also have begun, however basic, about creating a sports bar-themed lounge at Stan Sheriff Center that may feature food and entertainment, or a place for donors to watch postgame interviews rather than battling traffic immediately after a game.

“You have to win every day,” he says. “Win every day and eventually you are going to regain the confidence of the people, who will know that their money is going where they wanted and they will have a deeper sense of engagement.

“The public dialogue is that the athletic department needs to do more. The reality is that the amount of funding that’s going into it has either stayed the same or has gone down, but the expectations continue to stay high.”