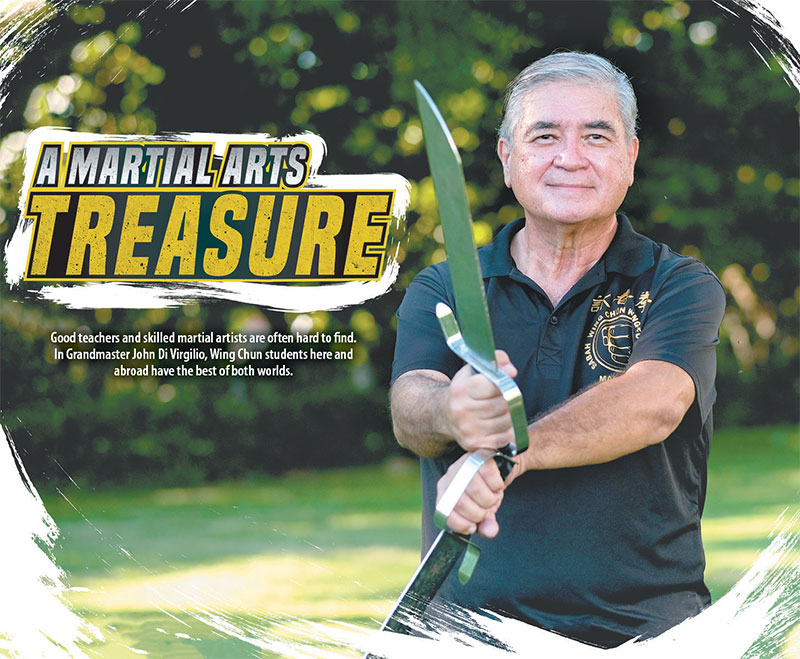

A Martial Arts Treasure

Good teachers and skilled martial artists are often hard to find. In Grandmaster John Di Virgilio, Wing Chun students here and abroad have the best of both worlds.

When it comes to teaching, John Di Virgilio is a natural at it. His lessons are always well-researched, well-structured and invariably well-communicated. And even in those rare instances when his words are insufficient at creating understanding among students or strangers, he’s always more than willing to teach through action, too.

Such was the case years ago when a somewhat cocky stranger — after having heard of Di Virgilio’s background in kung fu — approached him with a question. Specifically, it involved the 1-inch punch popularized by Bruce Lee.

John Di Virgilio does baat cham do touch drills with Kalin Ito during a visit to Ko‘olau Wing Chun Academy in Kahalu‘u. PHOTO COURTESY JOHN DI VIRGILIO

Despite Di Virgilio’s careful explanation of the technique, the stranger refused to believe his words. So, the veteran teacher chose to take a more hands-on approach to the question.

“I told him, ‘You know what? I’ll just hit you lightly in the center of your chest. You can tell me what you think about the punch, OK?’” recalls Di Virgilio.

The stranger agreed and braced for impact. Suffice to say, he wasn’t on his feet for very long because the short punch sent him sprawling over a nearby hedge, where he landed flat on his back. Thankfully, he was OK — although his ego was likely bruised.

Di Virgilio (standing directly behind his seated sifu, Robert Yueng), began his training in Wing Chun in the mid-’70s. PHOTO COURTESY JOHN DI VIRGILIO

As for his query about whether sufficient striking power could be achieved from an inch away, well, Di Virgilio wound up answering that question in quick and decisive fashion.

Understanding achieved. Lesson accomplished.

“I remember him telling me afterward, ‘It didn’t look hard, but I sure felt the punch!’” recalls a chuckling Di Virgilio.

For the Wing Chun grandmaster and former president of Hawai‘i Wing Chun Kung Fu Association, helping others attain greater knowledge in the Chinese martial art is just part of what makes him tick.

In 1980, Di Virgilio began studying under two of Ip Man’s most venerable students — (from left) Wong Shun Leung and Wong Chock. PHOTO COURTESY JOHN DI VIRGILIO

“But, knowledge is for those who dare take the chance,” adds the former Jefferson Award winner and public school teacher, who retired in 2016 after nearly three decades of working for the state Department of Education. “If you don’t reach out and grab it, it’s going to pass you by.”

Little wonder why even in retirement, the 67-year-old Di Virgilio is constantly approached by kung fu sifus eager to tap into his vast wealth of martial arts knowledge and all unwilling to let this Wing Chun treasure pass them by. As a result, Di Virgilio often spends his time with teachers and students on the West Coast to far-away locales as Malaysia and Japan, where his application insights and keen ability to explain the system’s sets and forms are always appreciated.

“I’ve never been one to advertise myself,” says the low-key Di Virgilio when asked about his growing demand as a traveling instructor. “Sure, I’ve gone around visiting the other (sifus) and helping them out, but it’s only because I’ve found it most useful doing it that way. I get to coach here and there and fill in the blanks wherever else there is need.”

Wing Chun is a centuries-old, concept-based system known primarily for its heavy use of the sticky hands technique called chi sao and for being named after a woman.

“It’s a very open-minded system in that there’s no one size that fits all,” explains Di Virgilio. “It’s not a fighting system in and of itself, but one that gives you a core foundation with tools to help you find your own way.”

The system first burst upon the international scene in the mid-’70s, thanks mostly to the Bruce Lee phenomenon. At the time, many of those caught up in the kung fu cinema craze wanted to simply know who taught Lee to fight, and when it became clear that the international movie star had studied briefly under Wing Chun master Ip Man, schools began popping up all over the planet to satisfy the growing interest among martial arts fans. Decades later, Wing Chun would get another boost in popularity after Donnie Yen began portraying the legendary master in a series of Ip Man movies.

This is where Di Virgilio’s martial arts lineage helps explain — at least in part — why he’s such an in-demand instructor.Although he did not learn directly from Ip Man, Di Virgilio did study under several of the kung fu grandmaster’s most notable pupils. They include Ip Man’s most senior student, the famous Wong Shun Leung, who earned the nickname “King of Talking Hands” during his younger days due to his success in Hong Kong’s street fighting competitions, and who was Lee’s primary teacher; and well-known practitioners Wong Chock and Wong Long.

Di Virgilio also worked closely with “Uncle Tommy” Yuen Yim Keung — a Wong Shun Leung disciple whom Di Virgilio credits with preserving the butterfly sword system known as baat cham do.

One of Wong Chock’s best students was the Kowloon-born Robert Yeung, an aggressive young fighter with a judo background who, along with his wife, moved to Hawai‘i in 1971. (Yeung would go on to establish the islands’ second Wing Chun school that could trace its roots back to Ip Man. The first belonged to Stanley Au.) Less than two years later, Di Virgilio, then just 18 and contemplating a career in college football, crossed paths with Yeung while working out at the YMCA in Nu‘uanu.

Their connection wasn’t immediate, but the encounter turned out to be the first step in an eventual lifetime partnership.

“I was at the Y getting ready for football when I met him and one of Bruce Lee’s students, James DeMile. They were giving a demonstration there and making a comparison between what Bruce Lee taught James and what a classical Wing Chun guy like Robert would do,” explains Di Virgilio. “I thought James DeMile looked really good with his one-step actions, but Robert was able to (string together) multiple steps and his hands system was more unified. I remember being so impressed with what Robert was doing.”

Di Virgilio wound up studying under DeMile for about six months before deciding that he wanted Yeung as his teacher. Yeung, however, refused to take him in and Di Virgilio suspects it had to do with the instructor’s close relationship with DeMile and his unwillingness to poach students from a friend’s school.

Whatever the reason, Di Virgilio remained undeterred. While other prospective students eventually gave up waiting around for an official invitation to join class, Di Virgilio kept showing up at Yeung’s school on Hotel Street. He’d patiently wait on the sidelines and quietly observe Yeung’s lessons, making copious mental notes along the way.

Eventually, Yeung gave in and told Di Virgilio to join his class. Not surprisingly, Di Virgilio already knew more than many of the pupils who had been studying with Yeung for months.

“I wasn’t just going to sit there and do nothing, so I would learn the forms indirectly,” he recalls. “At the time, I was a young guy looking for something that I felt I needed as a core. My thing was to challenge myself in a martial way and to see improvement.”

His growth in Wing Chun was quick and Yeung soon recognized that his newest student had much to offer the school. One day in 1975, Yeung asked Di Virgilio what he would do to improve the system of drills known as san sik if given the opportunity. Before the student could answer, the teacher requested a detailed plan by the following week.

Not wanting to waste a minute, Di Virgilio immediately went to work. By breaking down the san sik steps to their bare essentials, he was able to codify them into a more perfect system. Today, that system is enjoyed and practiced by scores of students both here and abroad.

“Robert Yeung used to say, ‘There’s imperfection everywhere — in oneself, in others and in things. But a true master knows how to work around or with this,’” says Di Virgilio.

Indeed, the student — who would eventually turn into the successor at Yeung’s school — was well on his way to becoming the master.

Besides being a teacher at heart, Di Virgilio is an ardent student of history — and most notably when it comes to military chronicles. In the last seven years, he has carefully researched and co-authored three books on the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (No One Avoided Danger, This is No Drill and They Are Killing Our Boys). A fourth book is scheduled to go to print later this year and a fifth one is tentatively slated for release in 2023.

“We’ve been working hard on the books,” says the former director for Pearl Harbor History Associates, who was presented with the Emperor’s Award in 2015 for his efforts in “creating acts of reconciliation and renewed friendship between Japanese and American veterans. “The books have been something of a calming point for me.”

His military focus also makes sense considering his parents both served in the U.S. Army, and one of his master’s degrees was in American History with an emphasis on American military history. His first master’s was in Education Curriculum.

“My dad was a major and my mom was a lieutenant nurse,” explains the oldest of six children born to Louis Di Virgilio and Sadie Yoshida and raised in Kailua.

While he loved the military stories he’d hear in his youth, his eyes were always fixed on the kung fu realm. Yet, despite desperately wanting to study a Chinese-based style and find “Asian cultural enrichment through a martial art,” he was rebuffed at every turn until De-Mile and Yeung came along.

“Actually, my very Chinese grandmother tried to get me into (kung fu) classes, but they wouldn’t let me in because I wasn’t Chinese enough,” recalls Di Virgilio. “So, I was kind of let down as a kid and wound up spending most of my time trying to get into high school sports.”

Finding success in football as a starting center and backup outside linebacker at Kailua High, he was able to parlay that rugged gridiron demean-or and adept mind of his into a solid foundation built on brawn and brains.

Turns out it was his physical nature that made Wong Shun Leung take notice of him when the two first met in 1980.

“Wong Shun used to say that a lot of Chinese practitioners were a bunch of scaredy cats who didn’t like getting hit,” remembers Di Virgilio, who would spend many of his adult years coaching football at his alma mater. “When he found out that I was a football coach, he really liked that.

“I mean if you don’t like getting hit, you’ll never be a martial artist.”

But with lots of practice and patience, you might just become like John Di Virgilio, one of martial arts best teachers and rarest of treasures.