The Picture Of Health

Kalei Hosaka and Wilfred Del Mundo II, who are both slated to graduate with their medical degrees in 2021, pose with University of Hawai‘i at Manoa’s John A. Burns School of Medicine dean Dr. Jerris Hedges at the 2017 Men’s March Against Domestic Violence. PHOTO COURTESY TINA SHELTON

University of Hawai‘i at Manoa’s John A. Burns School of Medicine does more than train the next generation of doctors. It also equips them to be productive leaders in society who care about the communities they serve.

There’s a lot going on at the state’s leading medical education institution, and it’s a lot more than meets the eye, to hear dean Dr. Jerris Hedges tell it.

In addition to building up fantastic doctors and conducting leading research in the health care industry (including some pioneering work on Zika), University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s John A. Burns School of Medicine is making sure all who graduate from its ranks — including the most recent class of 73 physicians — put community and others first, while striving to make their island home a better place to live.

It might seem strange that JABSOM puts a lot of focus on areas other than training the next generation of doctors, but, to Hedges, that’s kind of the point. It all comes back to connectivity and interrelatedness, which is something founder John A. Burns envisioned more than five decades ago.

A lot of the work the medical school does is collaborative, whether it be with insurance providers, health care institutions, nonprofits or advocacy groups.

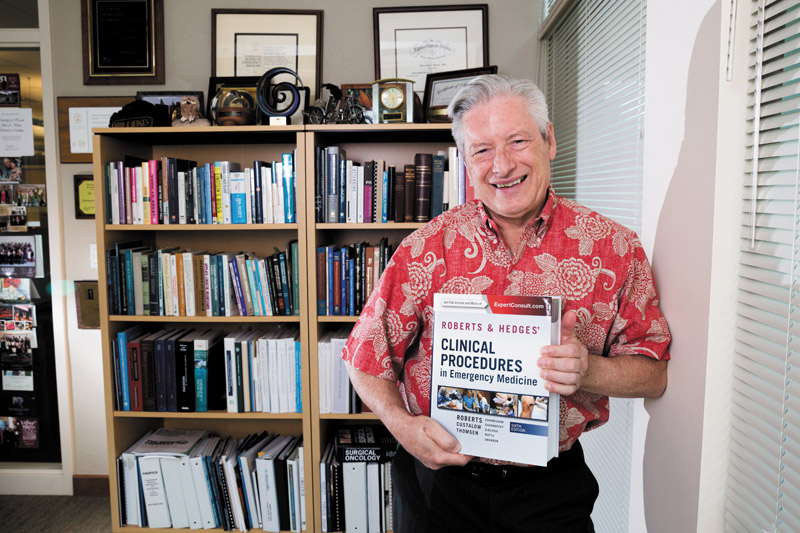

Dr. Jerris Hedges, dean of University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s John A. Burns School of Medicine, has co-authored books about emergency room procedures. ANTHONY CONSILLIO PHOTO

“We’re quite interested in the big picture,” he adds.

That’s why JABSOM is not just about turning out doctors.

“Rather, it’s about advancing health care in Hawai‘i,” Hedges adds. “Yes, we need to train doctors to go out and teach and practice, but our doctors have to be part of society. They have to be leaders in society, and they have to understand how their contributions will move society ahead, or we can’t bring health care to all.”

That’s why JABSOM and its faculty and staff make sure that each arm of the medical school is running smoothly and has adequate support.

Take, for instance, its research enterprise. That arena sees upand-coming professionals look at how to best address disparities amongst Hawai‘i’s various populations. JABSOM’s research arm is always a way to move science and health care forward, which is an obligation the medical school takes seriously.

Research that takes place elsewhere in the country doesn’t always apply to Hawai‘i. Populations vary by economic status, race, ethnicity and environment, to name a few.

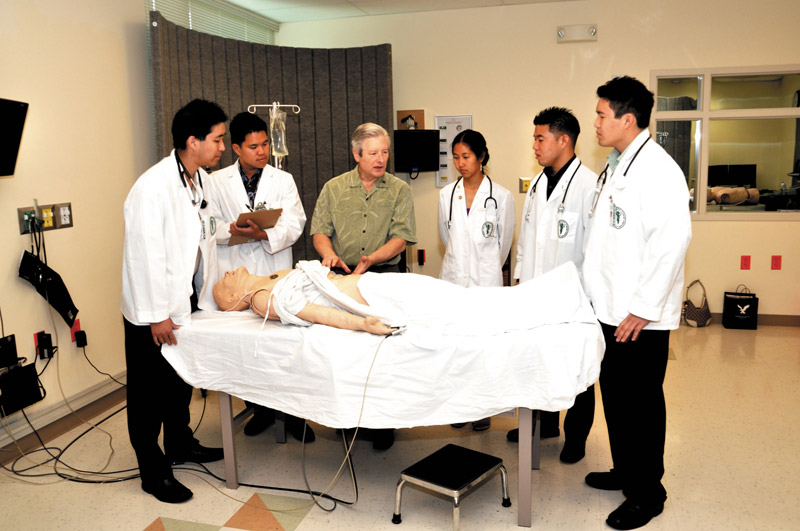

Dr. Jerris Hedges goes over patient care with medical students at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s John A. Burns School of Medicine. PHOTO COURTESY TINA SHELTON

Because of Hawai‘i’s location and classification as a small land mass surrounded by water, exposure to foreign illness and disease is a big concern. JABSOM’s Department of Tropical Medicine, Medical Microbiology & Pharmacology, for example, has done some of the leading work on Zika, and even though Ebola is not an issue here in the state, the team has been working with Hawai‘i Biotech to create a heat-stable vaccine.

“There is a relative vulnerability to any small land mass that has visitors,” Hedges explains. “So we’re very in tune to that (immunizations).”

Closer to home, students and faculty research the impact of diabetes, heart disease and obesity on our local populations, and look at various approaches and treatments.

“It isn’t just research for research’s sake,” Hedges adds. “These research components give a richness to the education that the university delivers, which our students are exposed to.”

Another enterprise is that of collaboration. JABSOM students work closely with those in nursing, pharmacy, social work and more, which results in a hui of health science leadership.

“We work on training together because you don’t want nurses and social workers to be suddenly thrown together in a hospital setting after their training and not understand how each other’s profession works,” Hedges explains. “That way, we can deliver better care and education.”

Hedges and the rest of the JABSOM team are now looking at how to effectively grow its class sizes, which is no easy feat. When the Kaka‘ako-based facility was erected in 1965, it wasn’t built for the robust cohorts of today (when Hedges started 11 years ago, the graduating class totaled a little more than 60).

Part of the curriculum involves one-on-one mentoring from doctors from various hospitals and practices. That close-knit mentoring seems costly in terms of manpower, but to Hedges, it’s absolutely necessary.

“It’s time-consuming,” he admits. “But you wouldn’t want it any other way. You wouldn’t want a doctor taking care of you to be someone who hasn’t had that oversight and observation.”

In addition, lack of funding keeps the classes growing in small increments. But any growth at all, Hedges adds, is good because it shows that the passion for health care is there.

“We have more talent here in Hawai‘i than spots in the medical school,” he says. “It’s heartbreaking when we have to limit the class size every year.”

JABSOM’s ability to attract local students and its capacity to provide excellent classroom and clinical training is good for Hawai‘i as a whole.

“If someone does medical school here, they’re more likely to be practicing here when they’ve completed their training,” Hedges explains. “We also believe they’ll do a better job because these are their neighbors, their family members — these are people that they’re going to care about above and beyond.”

To instill that sense of community, JABSOM requires all of its students to lend their medical talents to some sort of ongoing community service project. For example, 80 percent of them work in the school’s H.O.M.E. (Homeless Outreach and Medical Education) Project, which sees them bring medical supplies and care to various homeless populations around O‘ahu. Another is H.Y.P.E. (Hawai‘i Youth Program for Excellence), which helps homeless teens not only gain access to adequate medical care but also acts as a means of social support.

“Our students need to interact with patients, often those with the greatest need, to better understand the situation they’re in and what they can do to help,” Hedges explains. “They are more likely to be a strong part of the community, more likely to give back to the community, and more likely to build strong ties that will last generations.”

MORE ON HEDGES

One would think that the head of a medical school would have their background and training solely in health care. But for University of Hawai‘i at Manoa’s John A. Burns School of Medicine dean Dr. Jerris Hedges, a myriad of experiences and educational ventures have played a part in his current role as head of the medical school.

While, yes, he does have extensive history as a medical professional — most notably with Oregon Health & Sciences University, a level-one trauma center in Portland — a big part of what makes his tenure at JABSOM so critical is his big-picture approach to health care and how it impacts Hawai‘i.

But his interest in the sciences started long before that, while he was attending community college in his small Washington state hometown. There, he went into the school’s strongest science program, which at the time was engineering. Then, after transferring to University of Washington in 1969, he pursued a degree in aerospace engineering. His love of knowledge didn’t end there, and Hedges applied to medical school — JABSOM, in fact — after graduating with his bachelor’s. JABSOM didn’t accept him.

Not one to be deterred, Hedges did the next best thing: He got a master’s degree in chemical engineering. He then obtained his medical degree from University of Washington.

“What I liked about engineering is that you solve problems that have many applications, and there’s clearly a systems perspective in engineering where you look at the big picture,” explains Hedges, who has led JABSOM for the past 11 years. “It’s very applied. And that was what I liked about medicine. You are solving problems. It took information from many disciplines, and you sort of got a snapshot of society as a whole and the issues that society is facing as it was trying to build a healthier future.”

And, it seems, Hedges was on to something all those years ago. The blending together of health care and engineering has grown in popularity, and now one of the biggest fields in the engineering arena is that of biomedical engineering.

“I saw engineering as a way to bring new concepts into the (health care) field,” Hedges adds. “And UH Manoa just launched its biomedical engineering program.”