Liberators And The Lost

As Holocaust Remembrance day nears, two honolulu men recall the day they helped liberate prisoners at the Nazis’ Dachau prison camp

As time moves pertinaciously forward, as the Greatest Generation becomes the great-grandparents of Millennials, the stories of our history begin to become just that: stories. Even the largest tragedy of the 20th century, the Holocaust, begins to fade like an old photograph in the minds of the world 70 years after it was mercifully ended by the Allies’ victory over the Nazis.

mw-nm-040815-nazis-2

According to a global poll conducted in 2014 by the Anti-Defamation League, only 54 percent of the population had even heard of the Holocaust, while 32 percent of respondents believe the events had been greatly exaggerated or are a myth.

To help prevent the spread of such ignorance locally, City and County of Honolulu has proclaimed April as Holocaust Remembrance Month, and the state has named April 12 as Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Ceremonies will be held Sunday at Temple Emanu-El in Nuuanu, with representatives from various faiths, as well as Gov.

David Ige and Mayor Kirk Caldwell expected to attend and light memorial candles at the service.

“In Judaism, when someone’s parent, spouse, sibling or child dies, it is traditional for that person to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish in order to add merit to his/her loved one in the eyes of God,” explains spiritual leader Ken Aronowitz, who in July will be ordained as rabbi at Temple Emanu-El.

“Because entire families were murdered during the Holocaust, there were no surviving family members to say Kaddish, which is why the entire community will do so at our Holocaust Remembrance Service. Every man, woman and child murdered by the Nazis deserves this and should never be forgotten.”

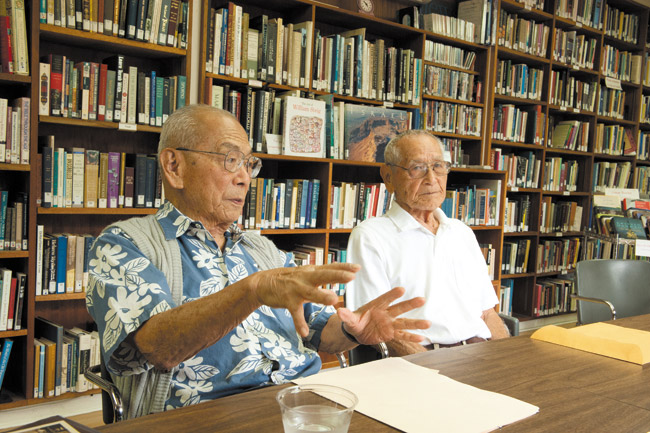

In 1945, the Germans were in full-scale retreat from the Allied Forces, and many of the men at the vanguard of this push were members of Hawaii’s own 522nd Artillery Battalion, an arm of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Two of the surviving members of this battalion, Masayuki Higa and Joe Obayashi, will be at the services this weekend to recount their experiences as firsthand observers of the end of this atrocity.

“They talk about us as liberators — to me that is a very big word. As far as I was concerned, I was only a scout,” says Obayashi, who thinks of himself more as cannon fodder than hero.

“We were there to draw fire, we were expendable, but all through there I did not see any German troops, no American troops, maybe one or two civilians. It was just like a vacuum, where you feel out of place. I told my captain, ‘I feel real awkward.’ Something was missing: movement. There weren’t even any animals except for two dead horses.”

The 522nd made their march through southern Germany in April and May 1945, crossing the Danube River and encountering several sub-camps of the notorious birthplace of the Holocaust’s genocide: Dachau concentration camp.

“We just came across where they were — we just happened to be crossing,” recalls Higa. “I had no idea what we were going to find. I didn’t know that they had a prison camp like that, they (our leaders) just gave us a direction.”

Both men are reticent to say who was the first to free the prisoners. The years and conflicting stories of others have muddled those facts, but what they never can forget are the men and women they saw during their campaign.

“We saw hundreds of people in striped clothes just wandering around because they didn’t know where to go and there was nobody to tell them where to go,” remembers Higa.

“Some of them were walking, some of them were crawling, some of them were on the ground — we could not tell if they were dead or not, but you look at them and it was pitiful,” says Obayashi. “That was the experience we had.”

One of the prisoners they discovered was a man named Solly Ganor, who wrote a book titled Light One Candle chronicling his experiences and eventual salvation by the 522nd:

“On May 2, soldiers from the 522nd were patrolling near Waakirchen. The Nisei saw an open field with several hundred “lumps of snow.” When the soldiers looked closer, they realized the “lumps” were people. Some were shot. Some were dead from exposure. But hundreds were alive — barely. I was among the liberated ones. My name is Solly Ganor.”

Once outside the gates of these death camps, the prisoners looked to the most unlikely of places for sustenance.

“There was a dead horse lying outside the camp next to a little stream when we were coming by,” recalls Higa. “We came back a few hours later and it was picked clean of the meat. It was something really bad to see — when we came back it was just bones, and all the prisoners were gone.”

Despite the depravity of their circumstances, Obayashi marveled at how they had not allowed their humanity to be taken from them.

“Prison breaks, you usually have a lot of riots and everything, but this was all very peaceful, like ‘What are we doing out here?’ They were so downhearted or numb, so to speak,” says Obayashi. “They all wanted food, but we had messages coming down to us not to feed them, but they were hungry so we give them anyway. Old men were drinking coffee and they were very courteous, nobody was rushing, sharing with one another and very polite.”

In 2010, Ganor wrote a poem dedicated to the men of the 522nd Battalion, and while the survivors of World War II are fewer every day, their memories are preserved for history in words such as these:

I lay in the snow ebbing life surrounded by death.

One looked at me with staring eyes he had a bullet in his head.

I heard the shots of the German guards their curses echoing through the forest,

I heard the bullets thudding into the bodies of my friends lying by my side,

They had no strength to scream before they died,

Many were just lumps in the snow shot or frozen a few hours before their liberation,

After years of torture, beatings, and endless humiliation.

I lay in the snow ebbing life a few heartbeats away from oblivion,

I saw the shadow of the angel of death as he spread his wings over my soul.

I felt the icy blood in my veins reaching for my heart. I knew my time had come.

I had a last look at the sky above and saw another Angel smiling at me.

His wings were just a dirty uniform and he had slanted eyes.

He picked me up from the freezing snow and gently stroked my head,

He wrapped me in a blanket and snatched me from the dead.

For more information on the Holocaust Remembrance Service, call 595-7521 or go to shaloha.com.