History Comes Alive With ‘Hawaiian Google’

A new program allows volunteers to put Hawaiian language newspapers online

There are three types of history buffs: Those who study it, those who write it and those who make it happen. Which are you?

If you say all three, Awaiaulu wants you!

On computers at homes, on iPads and at public libraries everywhere, folks are tapping out searchable text from Hawaiian-language newspapers that is making history. So far, 2,500 individuals have signed on to help in a massive volunteer effort that will involve thousands more including you, they hope.

nm_2

The scale and scope of Awaiaulu’s project is mind-boggling. What seems like a modest homegrown effort is akin to uncovering the Egyptian hieroglyphic Rosetta Stone in 1799, or the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947.

If you can’t relate to history that ancient, let us put it in modern context.

When completed, Awaiaulu’s ‘Ike Ku’oko’a project to transcript 60,000 pages of newspaper text, will be a Hawaiian Google.

OMG. Imagine being able to search on the Internet by key Hawaiian names, places or words that brings up documents from rare archived newspapers. Rather than anecdotal evidence or English language sources based on assumptions and interpretations, one would read text from the original Hawaiian-language source.

“We’ve only finished one-fifth of what we have. But that has already changed what we know about Hawaiian history,” says Puakea Nogelmeier, executive director of Awaiaulu, a nonprofit organization dedicated to developing Hawaiian knowledge resources and research for present and future generations.

‘Ike Ku’oko’a (liberating knowledge) is a Hawaiian newspaper initiative where volunteers are taking 60,000 digital scans of Hawaiian-language newspapers and transcribing them into searchable typescript.

According to project manager Kaui Sai-Dudoit, “Of the 125,000 Hawaiian-language pages originally published between 1834 and 1948, 75,000 have been found and made into digital images, and 15,000 of those images have been type scripted by OCR (optical character recognition) or manually.

“Our goal is to make the whole available collection word-searchable, and to do it by July 31, 2012,” Sai-Dudoit adds. “It will open up hundreds of thousands of pages worth of data on history, culture, politics, sciences, world view and more.”

Imagine being able to read about the political mindset of the Hawaiian royalty and its subjects during the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy.

According to Nogelmeier, there’s only a sliver of enlightenment about such subjects because up to now the original Hawaiian-language sources have been largely ignored.

“A century of Hawaiian stories, ranging from social commentaries to ancient epics, have remained silent in archives for generations,” says Nogelmeier, professor of Hawaiian language at the University of Hawaii. “The impact of leaving most of the Hawaiian writings out of the mix of modern knowledge is that every form of history written, every cultural study undertaken and every assumption made over most of the last century should be revisited in light of those neglected sources.

“A handful of Hawaiian writings were translated and published in English, and those heavily edited translations have become the Hawaiian canon, the reference standard.”

Recognizing the need to bring original Hawaiian-language sources to light, Awaiaulu launched in November a massive program to recruit local volunteers to transcribe old newspaper pages into computerized data. That’s simply typing what is on the digital print into a text document. You need not speak or write Hawaiian.

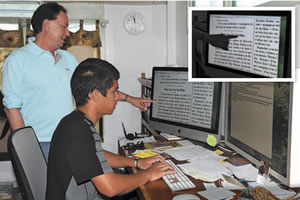

Awaiaulu and its team of programmers, checkers and reviewers, put together a user-friendly system that anyone with a computer and keyboard can follow. There’s even an online video, narrated by Nogelmeier, that shows the typical transcription process.

“It’s taking text that’s two-dimensional and making it three-dimensional,” the professor says.

To reward volunteers for their time, pages are labeled with the transcriber’s name or can be dedicated in honor of a family member or inspiring mentor.

The response to date, according to Sai-Dudoit, has been “remarkable.” The team got 1,000 email messages the first week from keiki to kupuna who want to be involved in the project. Not to mention the pride this project has instilled.

One kupuna in Seattle called Nogelmeier on the morning of MidWeek‘s interview to lament that she couldn’t get the public library to use the computer for her transcription commitment because of a snowstorm that shut down public bus transportation.

“Auwe,” he reacts, and thanks her for her heartfelt effort.

The volunteer initiative has gone global, with Hawaii interest groups such as hula halau, ex-pats and scholars wanting a hand in writing history. To date, about 1,345 pages have been completed, with another 1,104 pages on reserve by registered volunteers. Seems like a long way to 60,000 pages.

“But do the math,” Sai-Dudoit says optimistically. “If 30,000 of us took two pages each, or 60,000 took one page, we will reach our goal.”

Log on to www.awaiaulu.org to make tracks into Hawaiian history.