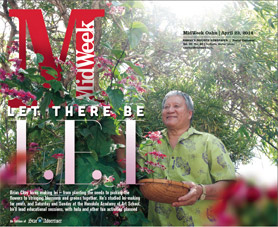

Let There Be Lei

Brian Choy loves making lei – from planting the seeds to picking the flowers to stringing blossoms and greens together. He’s studied lei-making for years, and Saturday and Sunday at Honolulu Academy of Art School, he’ll lead educational sessions, with hula and other fun activities also planned

There is something special about lei that goes beyond the visual and aromatic pleasure they invoke. Lei are living and wearable pieces of art that touch not just our senses, but our emotions. The right string of flowers can represent love, hope and friendship. It can say congratulations, welcome and get well soon. Beyond the aloha spirit and hula, a lei is perhaps the best cultural identifier of Hawaii. It is certainly the most recognized worldwide.

Yet those colorful strands of flower and leaf are often taken for granted. Oftentimes strung with imported flowers and made as quickly as possible to offset the economic challenges of producing a product that sells for less than its actual value, the best lei makers are finding it difficult to stay in the business.

That’s what makes this week’s Celebration of Hawaiian Lei Making at Honolulu Museum of Art School so important. The knowledge of lei making, especially traditional and complex styles, needs to be preserved and passed along to the next generation of artists.

This year’s event, only the fourth held at the museum in the past 20 years, came about in an unexpected way. The museum’s usually tight schedule had a sudden puka to fill, and art school director Vince Hazen had to scramble for both exhibits and funding. Luckily, both problems quickly were solved – another rarity in the museum business.

Hazen called longtime museum volunteer and lei-making veteran Brian Choy to head up the effort. Using $4,000 from Duty Free’s annual donation to the museum and four months of his own free time, Choy has lined up some of Hawaii’s best lei makers.

Putting on lei-making exhibits has been a learning experience for the 69-year-old former state Department of Health employee. His first show was ill-attended, he admits, because he wasn’t able to generate pre-event buzz. This year he has preceded the event with exhibits at several libraries around town. He also created posters and even got on the phone with local media.

It worked. “I’ve learned to hustle,” says Choy, who also had to work around the Merrie Monarch Festival, which always puts a premium on top-quality lei.

The exhibit, scheduled for this weekend, features lei-making demonstrations, hula by the May Day Lei Queen and Court, a talk-story session, the planting of a lei garden, and even lei-making Jeopardy. (In 2011, they did an Iron Chef challenge, where the artists had to create lei using surprise “ingredients.”) Among the lei makers scheduled, in addition to Choy, are Paulette

Kahalepuna, Roy Benham, Happy and Kats Tamanaha, Suzan Harada, Hui Hana of Lyon Arboretum, Velma Omura and Charlene Choy. Video presentations featuring lei historian Marie MacDonald and legendary lei-maker Irmalee Pomroy also will be screened.

While many of the displays will be familiar, Choy also has invited non-floral lei makers for the first time. “Typically, people think of leis being floral. But we got someone doing a paper lei. We invited someone from Ben Franklin, who will teach how to do the yarn and ribbon lei, which is a newer category in the May Day lei competition.”

These two invitations are something of a departure for Choy, who tends to focus on more traditional designs.

“Despite all my years fighting it, I did ask Ben Franklin to join us,” he says with his signature boisterous laugh. “I got caught up in that title, Hawaiian lei making. It was very traditional.”

His introduction to lei making likely explains his dedication to tradition.

Choy’s lei-making career began four decades ago while taking an ethnobotany class at Lyon Arboretum, taught by Beatrice Krauss. The final class project was a luau for which the students had to do everything; Dig an imu, roast the pig and prepare the typical dishes one would expect at a luau. When the cooking was finished, the students were given a half-hour lesson on making a lei po’o (which is worn upon the head) for the guests.

He was hooked. “It was agony,” says Choy with another big laugh. “We had to sit on this concrete floor. But I got so excited making this lei, and I met the Pomroy family, Irmalee and Walter, and I sort of became their groupie. I would follow them around. Whenever they were at a craft fair, I would sit there and watch.”

From there it became a journey to not only become a top lei maker, but to learn everything about the plants that make up the lei. Choy was a constant at lei-making events, mostly just sitting and watching, rarely asking any questions. He would rise at daybreak, sometimes dragging along reluctant children and other family members, to hike the trails around Oahu for his ingredients. Sometimes, he even flew to other islands to select specific plants.

For all the effort he put into studying and understanding the art, lei making was never much more than a passionate hobby. Choy tied lei for family and friends, including Kumu Ed Collier, and for at least one retailer friend who knew the right combination of pay and bribery (limu kohu poke) to pique his interest.

Today, his output is even more reduced. The reason is that lei making is cost prohibitive. It takes a long time to make a lei, and their low prices don’t leave much for the artists.