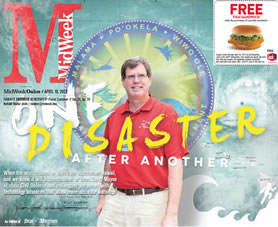

One Disaster After Another

Yet Mayne acknowledges that emergency managers operate today with vastly improved warning systems.

“Scientific and technological advances have really increased warning times,” he says. “This allows us to not spin-up people before they are actually needed.

cover_3

“I’ve spent my life in government service,” adds the Modesto, Calif., native. “I served 23 years in the National Guard and four years at FEMA responding to disasters and supporting authorities.

“Ninety percent of what we do requires the same action, whether it’s a natural or man-made (nuclear or bomb threat, terrorism, technological hazards) disaster,”

Mayne says. “We prepare for, respond to, recover from and mitigate disasters.

“Personal preparedness is key,” he emphasizes.

This applies also to businesses, which he suggests should have a business continuity plan.

“Forty percent of small businesses don’t reopen after disasters,” he says of the economic impact.

Even while dealing with those constants of crisis management, the force of change in our society, including the way people communicate and get information, is a perpetual storm.

“The role of social media in emergency management likely will increase in the future, and its impact will create a more complex and sometimes challenging operating environment,” in Mayne’s view.

Add to that demographic changes, such as an aging population and infrastructure, and you get a sense of what complicates future planning.

“I thank my lucky stars that I’m in Hawaii and get the kind of support we get from the Legislature,” Mayne says. “It is substantial.”

But is it always fair weather?

While metaphorically it might be, islanders know that, in reality, it is not.

To examine Civil Defense’s critical link to severe weather forecasting and monitoring, we head to the University of Hawaii Manoa campus and the National Weather Service Forecast Office (NWS) there.

The Oahu office, a division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), functions as the Honolulu Weather Forecast Office and Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Reports and alerts for weather-related hazards originate from a hurricane-proofed office on the second floor of the Hawaii Institute for Geophysics Building at UHManoa. The federally funded operation provides weather, water and climate data, forecasts and warnings. Each year, NWS collects some 76 billion observations and issues approximately 1.5 million forecasts and 50,000 warnings. Hawaii NWS does more than 20,000 forecasts a year.

Where one might naively expect to see weather vanes, barometers and meteorological geeks hanging their heads out the window, the NWS center looks no different than a corporate office of desks with computer monitors, remote terminals and phones. The 24/7 operation is manned by 35 meteorologists and 29 staffers.

While this might seem like overkill for a tropical haven like Hawaii, where the forecast is almost predictable from day to day, NWS has jurisdiction for the vast Pacific region that includes Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Micronesia, Marshall Islands, Palau and American Samoa.

Meteorologists use a combination of computer models, observation and knowledge of trends and patterns to do forecasts, aided by satellite and radar data. These models are used by agencies, private industry and news services in preparing daily forecasts that affect domestic, commercial and economic activity. NOAA refers to its mission as establishing a “weather-ready” nation.

Hawaii’s history of destructive hurricanes and tsunamis has made residents very receptive to preparedness information, according to Michael Cantin, NWS warning coordination meteorologist. He cites the close partnership with Hawaii State Civil Defense and other agencies to support the dissemination of information.

“Technology is designed to better pinpoint potential hazards earlier to give better lead time to react and make decisions,” he says. “Access to this information through the products we develop for public and other uses is essential in this age of instant communication.”

Gone is the folklore of farmers predicting rain when they saw cattle lying in fields or sailors anticipating storms with red skies. (Although Grandma’s knee pains were never wrong.)

In all of this, Mayne and Cantin underscore the importance of individual preparedness and kuleana (responsibility) for protecting lives and property in severe weather and catastrophic episodes.

Have a disaster kit. Have a disaster plan. Stay informed (www.scd.hawaii.gov) (www.prh.noaa.gov/hnl/).

In other words: Be prepared to help yourself, because they can’t help everyone.