The Heart Of Sacred Hearts

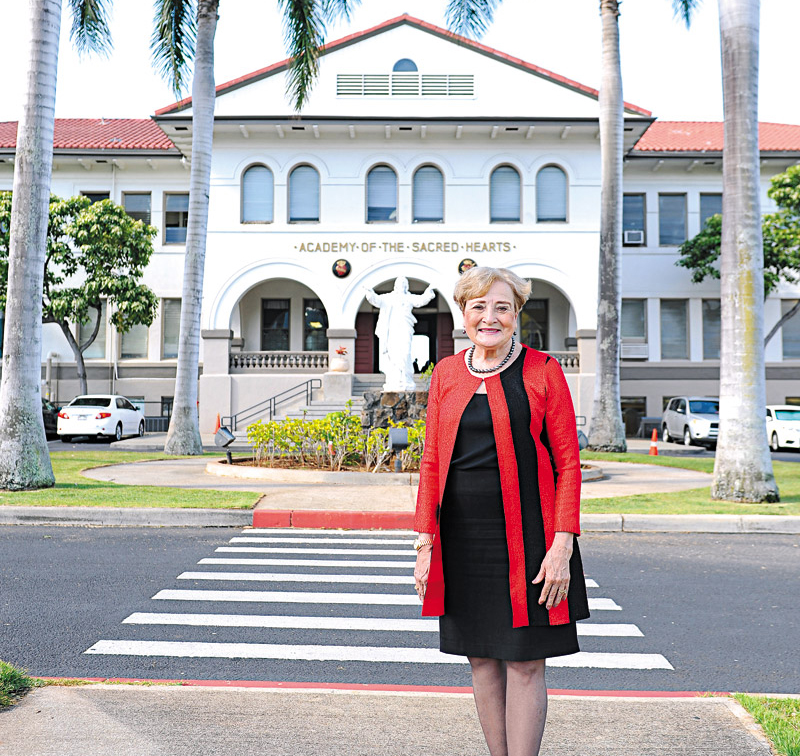

Head of school/principal Betty White is the first layperson to lead Sacred Hearts Academy. She will retire this summer after nearly a half-century at the school, and be replaced by Dr. Scott Schroeder. LAWRENCE TABUDLO PHOTO

From the day she first set foot on campus, Sacred Hearts Academy’s Betty White has given her all to its students, staff and community. Fittingly, she’s leaving her heart there after nearly 50 years of service.

Betty White is wearing a power-red suit. Her eyes are sharp and happy. She leans forward as she speaks and gestures with her hands.

“Heart,” she says, and pats her chest.

“Mind.” She points to her head.

“Hands.” She opens them, leans in again, and says, “That’s the service part of it.”

Those are the three things that have defined and guided the life and career of White. For just shy of a half-century, she’s dedicated her heart, mind and hands to the all-girls Sacred Hearts Academy in Kaimukī. This summer, White will retire as the academy’s head of school/principal, secure in the knowledge that she leaves behind a legacy of achievement and a blueprint for the future of her girls.

Before she became Sacred Hearts’ vice principal and later its head of school/principal, Betty White was a teacher who loved to fill students’ minds with knowledge of history and current events. PHOTO COURTESY SACRED HEARTS ACADEMY

As she departs her beloved school, she has a final message: “I think it’s important that women be at the table.”

Betty Louise Orr — or Betty Lou, as some call her — made her grand entrance into the world in December 1945, the middle child of five sisters and a brother. Her parents, Robert and Georgia Orr, didn’t have college degrees, but they had something better: bottomless love and endless support for every one of their children.

They raised their brood in the southwestern part of Virginia. When she was older, White learned it was the poorest county in the state, but she refuses to describe her family as poor.

“My upbringing was very humble, very simple,” she clarifies.

The Orrs always had food, a roof over their heads, and a car. She describes herself as a farm girl — summers were spent picking and canning corn, bushels of green beans and tomatoes. It was hard work.

Her graduating class had only 51 kids, and she estimates that 15 percent of her classmates went on to college.

“The fellows that I graduated with, they couldn’t wait to get to Detroit to work in the factories. But I knew that college was the path, and I had a very good counselor,” she says.

Other than her mother, that counselor, Lillian Richmond, was the defining mentor of White’s high school years.

“She had come to my little area of the state. She had married the superintendent of schools and was from Northern Virginia,” White recalls. “She made sure that I took the standardized test. She made sure that she told me paths I could follow. I owe a lot to her.”

According to White, Richmond was so determined to help them succeed, “she actually drove my friend and me to a testing center. It must’ve taken an hour.”

A good high school counselor is a beautiful thing.

Emmet White still remembers the first time he saw Betty Lou. Having just received his Army commission, he was a student at William and Mary Law School. She was attending the all-girls Mary Washington University. The schools shared a library, and that’s where he spotted her.

“I can still tell you, she had a red sweatshirt on, white jeans … and I saw her sitting two tables away,” Emmet recalls. “And I thought, well, that’s a pretty girl.”

He was too shy to approach her. When they finally met at a mixer, he was on his very best behavior.

“I toned down and tried to be a nicer guy,” he says. “She was quite a lady.”

It must have worked. One year later, he proposed — and White and her family accepted. She was the last of six girls to be married at age 24.

“Her aunt told me, ‘We’re so glad you married Betty Lou, because we were worried she’d never get herself a man,'” he recalls with a chuckle.

Back then, he continues, everybody in that farming community had an armory. So when the male relatives invited him hunting, Emmet figured it wouldn’t be a problem. After all, he was a lieutenant in the army.

“I thought I was hot stuff,” he says, laughing.

He soon learned that not only could White match his skill at hunting, but she could skin and dress the carcass and cook it, too. Turns out his future bride had skills.

“If everything went to hell in a handbasket, I’d want to be with her. She’s down to earth,” Emmet says. “They don’t make ’em like that anymore.”

After college, White discovered her calling. Her heart embraced the nurturing of children. Her mind welcomed the challenge to mentor young minds. Teaching is what she was born to do.

When she and Emmet arrived in Hawai‘i in a haze of young love, optimism and adventure in 1971, she answered an ad for a job teaching history at Sacred Hearts. Walking onto Sacred Hearts’ campus, she was eager to meet her first students. One of them was young Corlis Jean Chang.

“It was the first year she taught. We were a class of juniors,” recalls Chang, who now works as an attorney.

She and her classmates discovered two things about the young and pretty Mrs. White.

First, she was a great teacher who, Chang says, “brought history to life for us.” And second, she had very high standards.

One of the students’ first assignments was to read the newspaper every day — or else.

“She was demanding, in a good way — always giving us pop quizzes on what was in the newspaper, thereby encouraging — OK, forcing — us to read the paper every day,” Chang remembers.

White impressed on her students the importance of being aware of current events. She believed that history wasn’t just a study of the past, but a key to the future.

She stuffed their eager minds with knowledge. She loved her students. She respected them. They gave it right back.

“You should see the love that former students have for her,” Chang says.

Interior designer Cathy Lee, who graduated in 1983, says White was both her teacher and the vice principal by the time Lee was in her class.

“The thing that struck me about her from day one is she was always such a lady,” Lee remembers. “She was strict, but kind. She had a sense about her that she was approachable, but firm. Compassion just radiated from her.”

As White transitioned from teacher to VP to principal, her mission crystallized. The world was changing fast, and Sacred Hearts needed to change with it to be relevant.

“I wanted to take that history and the mission, but I still wanted to be innovative, keep the good parts of the past,” says White, the first layperson to head the Catholic school. “I wanted project-based learning. We wanted robotics. We wanted all sorts of leadership programs. It was difficult because sometimes we were working with limited resources. But I always had a good staff, a good team.”

And she made it a point to develop excellent relationships with the community.

A stroll through the campus today reveals the fruits of her efforts: the Clarence T.C. Ching Student Center; Mother Louis Henriette Performing Arts Center; the McKeough Arts Center; and the Nobriga Gymnasium.

Most notably, White instituted the curriculum and career path known as STEM as a focus for Sacred Hearts. She also spearheaded efforts to beef up staff and facilities, including science labs and computers.

White knows women can and must be major players in this brave new technological world.

“They think differently, not better, not worse than men, but differently,” she observes. “They bring an entirely new perspective to whatever is on the table.”

This year, White hosted both the school’s 25th annual Science Symposium and the second annual STEM Symposium, open to girls from all Hawai‘i private and public schools.

“STEM jobs pay about 33 percent more than other jobs. So when I talk with our girls I ask them, ‘You want to be financially independent?’ STEM is where more lucrative salaries are.”

The third component of White’s philosophy, the hands, is steeped in her own upbringing.

“I remember by the age of 10 working with my family to help the elderly in our small community in Southwest Virginia,” she says.

They did everything from cleaning yards and running errands to picking up food from the local grocery store.

“Always the caution was given by our parents: refuse to take money for helping,” says White.

That early focus on service meshed perfectly with the mission of the academy.

Sacred Hearts’ students can often be found fanning out to homeless shelters, long-term care facilities and hospitals. They toil in lo‘i patches and pick up trash from beaches.

They study service issues in the classroom. They discuss potential solutions to problems such as homelessness.

White says service isn’t passive; it’s hands-on and proactive.

She is also confident that the academy’s new head of school, Dr. Scott Schroeder, will do quite well as he leads the academy forward. He’ll be the first male in charge of the all-girls school.

“The mission doesn’t change,” observes White. “(But) the way we choose to carry out that mission sometimes changes.”

Now it’s time to move on. White and her husband, a retired attorney, have three children and seven grandkids to enjoy. Emmet says he’ll have to teach his wife to be the chauffeur, for a change.

White chokes up, just a little bit. “He supported me,” she says. “The whole family supported me.”

“I took pride and great happiness in everything she ever did,” he adds.

The National Coalition of Girls’ Schools Board of Trustees is honoring White with the Ransome Award, for advocating for girls’ schools and educating and empowering girls on a local and global level. The ceremony will take place at the 2019 NCGS Conference June 25 in Los Angeles.

Emmet says Betty will be modest about it, but she deserves the honor and more.

“She’s an example. Iconic,” he says. “She’s a special woman, and there’s a goodness in her that’s unreal.”

Admire Betty White for her heart. Respect her for her brain. And give this long-time educator a big hand and mahalo for elevating the lives of girls in Hawai‘i.