Back on Board

That’s the title of a documentary on Olympic diving champion Greg Louganis that will be featured at Honolulu Rainbow Film Festival June 4-7 at Doris Duke Theatre and Kahala Consolidated Theatres. The film is all about him overcoming obstacles, from dyslexia to a distant adoptive father to prejudice because of his sexuality

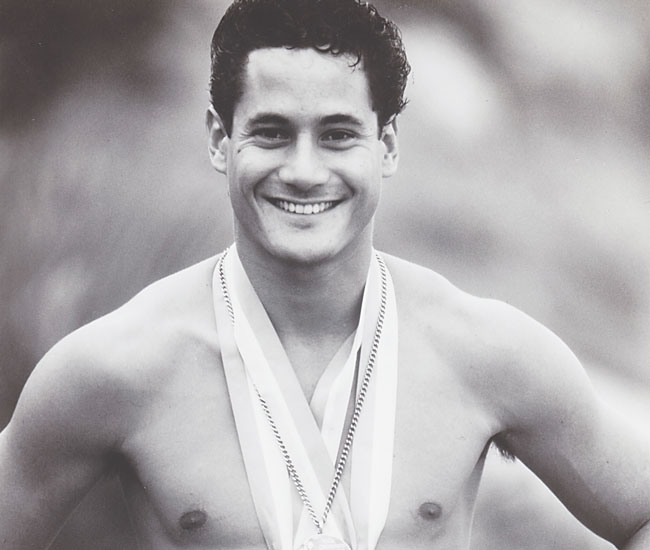

Minus the mane of gray, Greg Louganis doesn’t appear much different than his days of Olympic glory. He remains friendly, soft-spoken, handsome and is still able to pull off an occasional one and-a-half, so long as he has enough rest between attempts. These niceties are not enough, however, to warrant a prime spot at the 26th Honolulu Rainbow Film Festival — for that, a documentary needs to do more than tell a happy story.

MW-Cover-052715-Louganis3.jpg

Back on Board evokes nostalgia, joy, anger, frustration and the disgust over a line of questioning by Larry King, who paints Louganis as not a victim of HIV, but as an irresponsible and willing participant in the era’s most misunderstood morality play.

To speak with Louganis about his personal, professional and financial struggles is to hear not a tale of woe but of hope, acceptance and forgiveness. It’s this strange and fascinating story that makes Back on Board an example of first-rate filmmaking. Louganis could have been a local boy. A mix of Samoan and Northern European ancestry, the former five-time Olympic medalist would appear at home in any number of extended-family gatherings from Waimanalo to Makaha. His own upbringing, however, often lacked such support.

Louganis knew he was different from a young age, but how so didn’t become clear until later. He heard the conversations his friends were having about girls and knew, for some reason, he didn’t feel the same way.

“I didn’t put sexual identity to it, I just felt different,” he recalls. “I felt there was something wrong with me. I felt odd and awkward. I probably overcompensated by what I could do physically.”

Louganis loved to perform. He started tumbling before he was 2 and got involved with dance, theatre and his first love, gymnastics. Diving took over at age 13 after knee injuries forced him to drop the other activities. It wasn’t much longer until the taunts began.

Queer.

Faggot.

Sissy boy.

This is how he was known at school and around the pool. His Olympic teammates didn’t want to room with him. Some went so far as putting BTF (Beat the Fag) Club signs on their doors. The name-calling, which began in high school and continued throughout his Olympic career, was about jealousy, he says, rather than actual homophobia. Today, some of those former tormentors are friends.

Life at home wasn’t much better. His adoptive father Peter could be physically abusive and emotionally distant. Affection seemed to come with a price, and a teenage Louganis told his mother he understood how people could die from sadness. Diving, Louganis hoped, would lead to acceptance.

“It was something I was good at, but I wasn’t enjoying it at the time,” he says. “I was trying to win over my dad, because my dad had a difficult time dealing with my sexual identity. I thought I was letting him down, and the only way I would be deserving of his love (was to be a successful diver).”

“Retard” and “stupid” were other names he went by. His undiagnosed dyslexia left him feeling inadequate and the subject of ridicule. He found ways to stay after school, to limit the abuse and hopefully to curry favor with teachers. He cleaned chalkboards and tried to become a teacher’s pet, which just increased the namecalling. If an assignment called for him to read aloud in class, he would spend the night before memorizing the text so as to not call further attention to himself.

“I didn’t feel very smart. Growing up, I was called retard, moron and all that stuff, and I believed it. I knew there was something wrong because I didn’t learn like other kids.”

He finally got help in college after coming upon the word dyslexia in a freshman English class. For the first time, he understood why he lagged behind fellow students. “I realized I was not all the names people called me when I was a kid.”