Starring Role

IN CLAIMING THE 2020 NOBEL PRIZE IN PHYSICS, ASTRONOMER ANDREA CHEZ SHEDS NEW LIGHT ON BLACK HOLES AND THEIR INTIMATE CONNECTION TO THE EVOLUTION OF THE MILKY WAY.

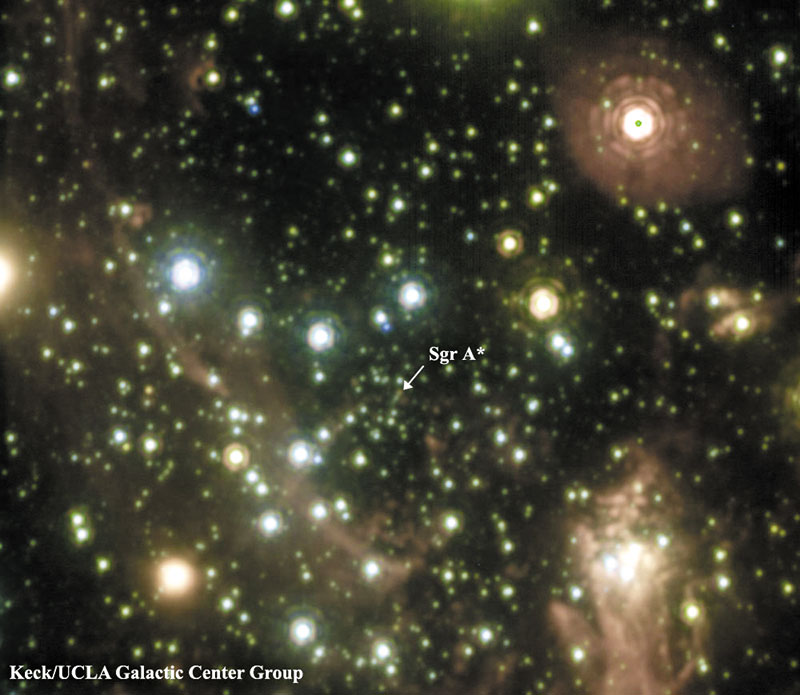

From W.M. Keck Observatory on Hawai‘i Island, Andrea Ghez made the pioneering discovery that our galaxy has at its center a supermassive black hole — known as Sagittarius A* (pronounced A-Star).

While tropes in movies and TV series describe black holes as gluttons of the cosmos that inhale everything in sight and grow to larger-than-life proportions, the UCLA physics and astronomy professor says these cultural myths reflect a general misunderstanding of these dense points in space.

“They get a very bad name as sort of a cosmic vacuum cleaner,” says Ghez, laureate of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics.

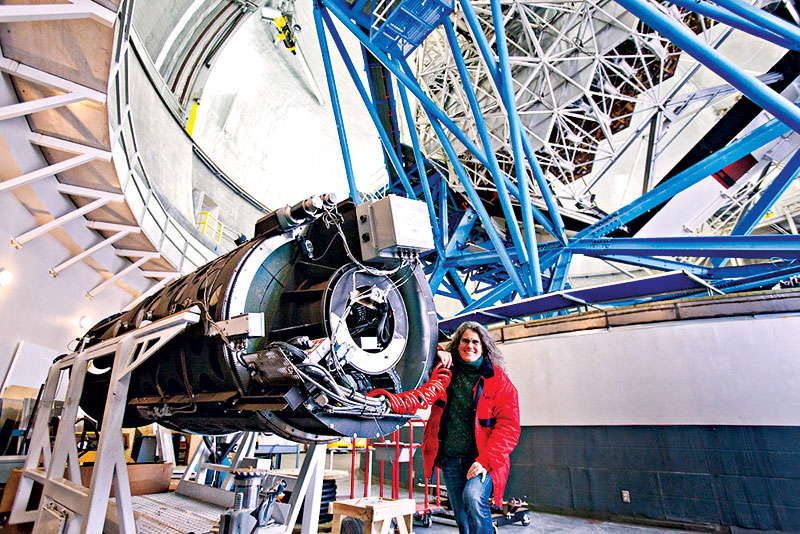

Andrea Ghez and members of the UCLA Galactic Center Group at W.M. Keck Observatory’s telescope facility on Mauna Kea. PHOTO COURTESY UCLA GALACTIC CENTER GROUP

Black holes, she explains, are strong sources of gravity that force celestial objects to orbit around them. As far as things getting “sucked in,” Ghez adds that a star will only fall into a black hole about once every 10,000 years or so.

The question of supermassive black holes, particularly those in the center of a galaxy, has been around for decades, but only within the past 30 years has technology improved enough to support solid claims. “We moved the case for supermassive black holes to certainty,” Ghez explains of the recent discovery.

“We think they’re intimately connected to the formation and evolution of our galaxy,” she continues. “It’s a central component, like it being the heart of the galaxy, or the key thing that sustains it.”

Furthermore, she found that the environment around a black hole didn’t look anything like what was expected, leaving researchers with more questions than answers.

“It just tells us that there’s so much more to learn,” she excitedly adds. “It’s all benefited by improving our technology. Today, we only see the tip of the iceberg. The center of our galaxy has become such an amazing place.”

The 27-year-long effort leading up to the discovery of Sagittarius A* earned her last year’s Nobel Prize, and is something she’s happy to share with Hawai‘i’s prestigious facility.

“This prize is such a wonderful tribute to Keck,” says Ghez, who first used the Keck telescope in the ’90s. “This is really about the science that Keck opens up, and it’s one of the best places in the world to do this kind of work.”

The sciences typically have fewer women in affiliated fields, but Ghez is excited to see more and more females stepping into leading roles — all while maintaining balance as working moms in an ever-busy world. She cites the work of Marie Curie, who won Nobel Prizes in chemistry and physics in 1911 and 1903, respectively, as well as her daughter, Irène Joliot-Curie, who won the same chemistry accolade in 1935, as women of note.

“They set a pretty high bar,” Ghez adds with a laugh.

For her part, Ghez is mom to a 19-year-old mechanical engineering major at Johns Hopkins University, and a 15-year-old whom she describes as “a builder, figure-itout kind of guy.”

“My kids have taught me so much,” she says. “They’ve helped me become a better scientist.”

Currently, the bulk of Ghez’s research focuses on the Milky Way and how stars form at the center of our galaxy, especially near Sagittarius A*.

“One of the early surprises was to find young stars,” shares Ghez, the oldest of three daughters born to an economics professor dad and housewife-turned-art gallery director mom.

Now, those same stars are allowing Ghez to take a closer look at how gravity works near supermassive black holes, as well as how black holes grow over time.

“Compared to other supermassive black holes, our galaxy is kind of a wimp,” she chuckles. “We live in a quiet, garden-variety galaxy.”

For her efforts in identifying Sagittarius A*, Ghez jointly shares half of the 2020 Nobel Prize in physics with Reinhard Genzel, while the other half was awarded to University of Oxford’s Roger Penrose. Though one would think going Dutch on such a prestigious award is a little odd, Ghez explains that it’s actually the perfect demonstration of what healthy competition can bring about.

“I’m really thrilled that the Nobel Prize recognizes all of us,” she says. “It gives it validity. These are hard measurements and (these) two groups independently came to the same conclusion.”

Her path to becoming a renowned astronomer in her field wasn’t as clear-cut as most would think. As a youngster, Ghez’s dream was to be the first woman on the moon.

“But I also wanted to be a ballerina,” she adds with a laugh.

Once she started high school, it was clear that she had a clear aptitude for math and science, and after graduation headed to Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then to California Institute of Technology for graduate school. Ghez, who initially started as a math major, grew to love the realm of physics, which, she says, addressed the kinds of issues and concepts she found to be most interesting.

Black holes, in particular, caught her attention early on.

“They’re objects that mix space and time, and defy our understanding of physics,” she shares. “It’s like a puzzle, and anything that’s a puzzle is intriguing as a researcher. You want to find interesting puzzles in which the solution can teach you more broadly about how to understand the universe.”