A Reluctant Hero Goes To Washington

Thanks to relentless work by friend Benjamin Ishida, Airman Albert Kalahana Kuewa’s name is finally inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C.

So, as you stand there weeping with your fingers on my name

Share with those cute grandkids the reason for this place

To restore some stolen gratitude and dignity

This granite wall of honor that holds my memory. -Lyrics from The Wall Song

Albert Kuewa

Wahiawa resident Benjamin Ishida is traveling nearly 5,000 miles on Memorial Day to face a wall. No, this isn’t some sort of punishment. It’s a moment of truth for a Vietnam veteran who fought a personal battle for 46 years on behalf of a buddy.

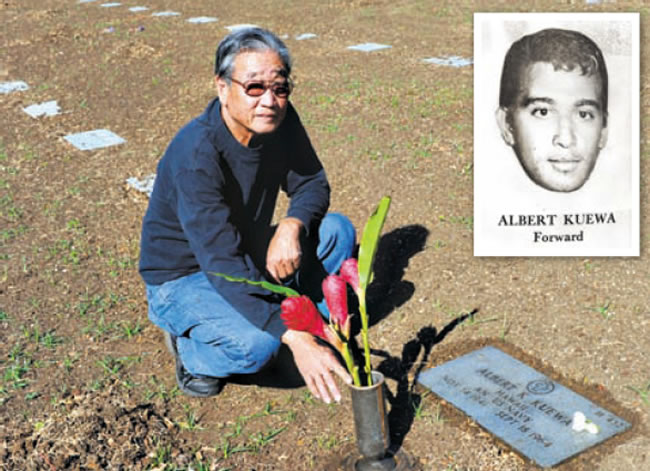

Ishida, 68, is making a pilgrimage to see the name of his Waialua High School classmate and Navy buddy, Airman Albert Kalahana Kuewa, finally inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C. He will see it newly imprinted on the black granite wall at Panel O1E, Line 063, one of 58,000 names of fallen heroes.

A day before the ceremony in the nation’s Capitol, Ishida will witness Kuewa being honored at the Waialua Lions Club 65th Memorial Day program at Haleiwa Beach Park. The program will feature a special and belated recognition of Airman Kuewa as his name is unveiled on the Lions’ Vietnam heroes plaque.

Both occasions will undoubtedly be emotional moments for Ishida.

Why did it take so long for Kuewa’s name to appear on the national and local monuments? Was there a miscarriage of military process, botched bureaucracy, or sheer neglect that caused this oversight?

More importantly, what in the human spirit causes a man like Ishida to pursue a mission so relentlessly for nearly five decades?

“I promised my friend before I die, I going figure this thing out,” Ishida says as he recalls a pledge to get Kuewa recognized for his sacrifice in the line of duty.

Ishida was on crash crew duty the fateful night of Sept. 18, 1964, when Kuewa died on board the USS Ranger in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of Vietnam. The carrier was conducting air reconnaissance missions over Laos, sustained for 12 hours daily, from noon to midnight.

“Kuewa worked on the flight deck,” Ishida recalls, “the worst job.”

It was an open arena to danger and combat fire, he explains. Kuewa was hit by a moving plane while in support of a mission in North Vietnam.

But the carrier log stated otherwise. Kuewa, it recorded, died after walking into a plane’s propeller while the carrier was idle.

“What a lie,” Ishida says.

As reported by KHONTV News, it turns out there were two logs and their mission was classified.

After bringing Kuewa’s body home and learning of the conflicting reports in the military records, Ishida set out on a personal mission to get the U.S. Department of Defense to recognize Kuewa as a casualty of war.

That took many years of research, persistent communications with military and government officials, and valuable support from the office of U.S. Sen. Daniel Akaka.

The result is that, after 46 years, the Department of Defense has evaluated the circumstances of Kuewa’s death and approved having his name added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall for ceremonies on Memorial Day.

“I told Albert that I have to see you on the monument,” says Ishida, a construction company owner and retired City firefighter. “I checked all the monuments (including the Korean-Vietnam War Memorial at the Hawaii State Capitol). Never had his name. That’s when I went to Akaka’s office.

“The thing I feel so bad about is that two days before (Kuewa died), I saw him by the crash locker. He told me he was tired, because he’s so big (6-foot-5, 270 pounds). I talked to the flight deck chief to move Albert from flight deck to crash crew. And then this thing wen happen,” he says remorsefully.

“I don’t want you to make me look like a hero,” Ishida tells this reporter. “That’s just the way I am. Nobody knew what I was doing all this time.”

Kuewa’s sister Grace confirms that.

“He carried the burden,” she says, “We are amazed that he did so much and can’t thank him enough.”

For others in the same situation, she implores, “Don’t give up.” What Ishida did for her brother – one of eight children and the youngest of four boys – is miraculous yet just.

It’s all the more noteworthy when one considers the still hotly debated public opinion about the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. While Ishida’s agenda is not political by any means, it is one story among many of the Vietnam conflict, which history records as the largest American war with conscription (mandatory enlistment).

“We went into this thing with honor,” Ishida says.

Yet America’s failed intervention in Vietnam has left many emotional scars. For families like the Kuewas of Waialua, there are haunting memories of their brave son with no true closure.

Thanks to a devoted friend like Ishida, there are small triumphs along the way, like the long-overdue recognition of Albert Kuewa for his ultimate sacrifice in the line of public service.

Ishida expresses this plight with candor on a bronze holder encircling the floral vase at Kuewa’s Punchbowl gravesite. It states, “It Took 46 Years Too Long. Brother-Ben.”

Donations to offset travel expenses for Benjamin Ishida to Washington, D.C., can be sent to Billie Gabriel, 105-B Kawananakoa Place, Honolulu HI 96817.