“A Nice, Safe Environment”

In the first-floor game room of Boys & Girls Club Honolulu there hangs a pool cue rack on a brightly colored wall. Despite nearly a dozen open slots in the rack, there are but two cues affixed to it. No one is playing the two tables currently. So where are the rest of the sticks? Is it budget cuts? Petty thievery?

Nothing so sinister — the sticks serve as a symbol, part olive branch, part baton, as it is passed forward in the race of life.

“We only allow one stick out for each table,” says club president Tim Motts. “Because kids need to learn to share, it’s not about what they are doing, it is about working together. Not only are they playing games but they are getting in arguments and figuring out who they are, and the hierarchy of life.”

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the club opening here in the cramped neighborhood of Moiliili — within walking distance of Washington Middle and Lunalilo Elementary schools — where it has served as a safe haven for youths of the area in this pivotal time in their development.

“Those years are critical years in most kids’ lives; having a place like this meant a lot,” says Brian Yoshii, a club member from day one, who worked as the chief regional officer for Kaiser Permanente. “Before that we were hanging out in pool halls. This is a nice, safe environment where we had good role models. They were always here, they may not teach you the secrets of the world, but they were here to push you in the right direction.”

Yoshii is still connected with the club today, serving not just on its corporate board, but also volunteering as a sensei in judo and coaching its baseball teams. The club’s impact goes well beyond filling some childhoods with healthy activities, but helps to change lives that might have otherwise gone astray.

The most important number for them is 104, as in 104 visits in a year. If they can get a kid to swipe their club card and come inside twice a week for a year, they begin to see real results.

“It is almost like the magic number,” says Motts. “We talk about the secret sauce, what makes the club special, why did it change our alumni’s lives. If you get a kid to come a couple times a week, they will say the club changed or saved their life.

“You’ll see Shaquille O’Neal or Denzel Washington holding their club card, they are very sacred to these kids because the club changed their life. We have alumni here who still have their card from 1981.”

Their impact is felt worldwide — the 150-year-old club is the world’s largest youth-service agency, helping 4 million kids a year at 4,000 clubhouses. The club’s roots can be traced back to Connecticut before the Civil War, when three women got together and decided all the boys they saw roaming the streets should have a more positive alternative.

As it grew throughout the years, they eventually opened it up to girls as well, officially changing the name to Boys & Girls Club in 1990, a welcome change that impacted so many lives, like that of Johna Leedy of Waianae.

In high school, Leedy kept getting into trouble, and in 2011 was given an ultimatum: time in a detention home or community service at the Boys & Girls Club through the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative.

“At first, I just wanted to get in and get out, then I started mentoring the kids,” says Leedy, who now works on staff at the Waianae Clubhouse, “helping them with their homework, and it was like I got stuck, but just the best kind of stuck you can get with kids.

“I went over there to do my community service and I didn’t realize that I was helping this kid with their education and social skills, and that is stuff that will help them when they get older. That’s what got me. You are helping that kid for when they get older and they will look back on you and think, ‘She thinks I can do it, so I should do it.’ And that’s hot.”

For many kids, it is just having someone care what you are up to that makes the difference, knowing there is a place you can go and belong. The heartbeat of each club, according to Motts, is the Games Room, where kids can just hang out, play pool or pingpong, chess or checkers, but most importantly interact with one another.

“You don’t see a lot of couches or TVs in the game room. This is a place of interaction and fun,” says Motts, who says everything is designed so the kids have to face one another. “That isn’t to say there isn’t down time, but you are not going to see 50 kids sitting in corners scrolling through their phones.”

Motts oversees 10 clubhouses between Oahu and Kauai that service 14,000 kids a year, with more than 100 employees and an equal number of volunteers. Before coming to Hawaii, he ran clubs in Los Angeles, where urban sprawl was his biggest obstacle.

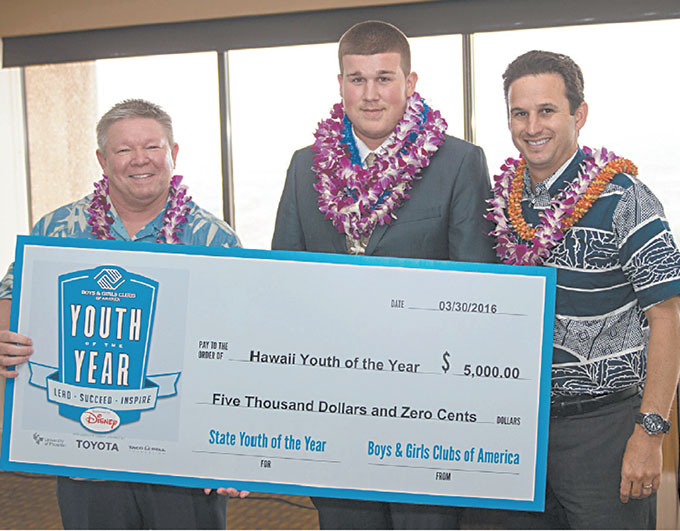

George C. Carroll III, M.Ed. (University of Phoenix), Jeffrey Jones (Hawaii State Youth of the Year/Waianae Clubhouse member and Waianae High School student) and U.S. Sen. Brian Schatz PHOTO COURTESY ROBERT CARR

“Here, if you build it, they will come,” says Motts, who took over here after former CEO David Nakada stepped down after more than three decades of service. “When this club was built 40 years ago, it was like a beacon. Kids just figure it out — they just make their way here, much more grassroots. In L.A., you had to do a lot of marketing. Here it is just word-of-mouth — hey, Boys & Girls Club is available for $25 a year, you would be crazy not to take advantage of it if you live within shouting distance of it.”

The low cost of membership means a lot of fund-raising has to go on to keep the club doors open. They estimate that it costs the club $1,000 per child per year to provide all its services. In addition to private donations, it receives help from such disparate groups as the Los Angeles Lakers, which donated $50,000 to create the Lakers’ Reading Room, and $150,000 from Rotary Club of Honolulu to refurbish the gymnasium.

The kids do more than just game here. There is Power Hour every day, when all the club activities shut down to focus on homework. There are 65 different activities for kids, from arts and crafts to cooking classes to computer labs, that Motts hopes will open doors for these children that would have been closed in the past.

“I don’t want it to be that just because you went to this school, you get to get these jobs, but if you go to that school, you get to have these jobs,” says Motts. “What about closing that gap? That is why we have the computers, robotics programs — we customize our programs to what the kids want to do.”

- Kaiser Permanente CIO Brian Yoshii, 1976 alumnus

- World Wide Technology senior project manager Steve Rodolfich, 1978 alumnus

- Youth development specialist Johna Leedy, 2011 alumna

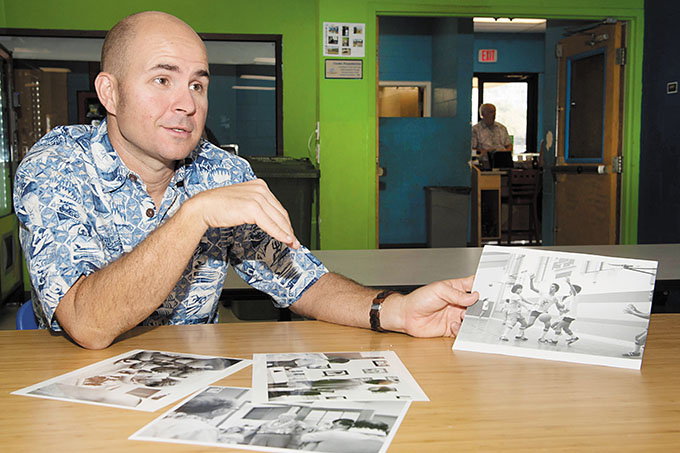

This effect can be seen in Steve Rodolfich, who started attending the club in 1978 as a 9-year-old and today serves as a project manager for World Wide Technology.

“When I first started coming here, my mom was a single parent and she just needed some place just to dump me off,” says Rodolfich. “It was a safe place for me. I forged a lot of friendships here that I still have today, and I got exposed to a lot of things I would not have otherwise, like arts and entertainment and sports teams, things that I didn’t have enough talent in to do outside of the club. It opened a lot of doors for me.”

In order to keep the doors open, the club will be conducting fundraisers in upcoming months.

You can find information on how to help out the Honolulu clubhouse or the ones in your area by visiting bgch.com.