A Look At What Makes Tiger Tick

In his ability to write a captivating historical narrative, Hank Haney is no David McCullough, and his book The Big Miss pales in comparison to McCullough’s Truman and John Adams. Then again, McCullough didn’t have to deal with a completely self-involved central character who never learned to deal with the tremendous pressure of not only carrying his sport but living up to outrageous family expectations.

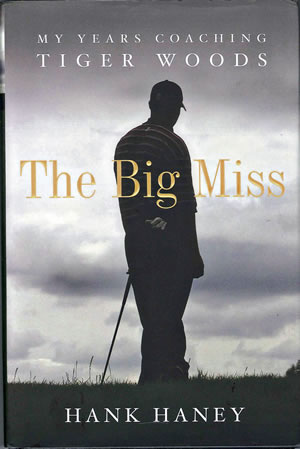

Yes, I’ve finally gotten around to reading the slanderous, scandalous, boring, fascinating and sad tale that is Haney’s recollection of seven years coaching this generation’s greatest golfer. By now you’ve heard everything about what a jerk Tiger Woods is and how keeping track of, and later reporting on such inside information, has revealed Haney to be nothing more than a modern Benedict Arnold.

Like Michael Jordan’s failed attempt at Hall of Fame levity, the media has missed its chance at fairly explaining the context in which The Big Miss was written. The tales of Woods being famously and, seemingly, enjoyably cheap, his disregard for fans, poor on-course behavior, his infidelity – all these juicy tidbits that have been replayed for months would-n’t fill a short chapter, let alone a 250-page book. The majority is complimentary and, if you don’t have much appreciation for or interest in the mechanical workings of a golf swing or the practice routines that create such action, quite boring. Haney also lets us know that the friendship between Woods and Jack Nicklaus grew more competitive as Woods climbed higher up the ranks of major championship winners, and that the famed feud between him and Phil Mickelson was hardly personal and based more on competition and differences in personality. Haney writes that Tiger enjoyed a hardy laugh when Mickelson sent a miniature pingpong table to Tiger’s newborn son Charlie, and that Tiger reached out to his biggest rival after Michelson’s wife and mother were diagnosed with cancer. The Woods/Mickelson Ryder Cup pingpong matches are the stuff of legend, and have for years exemplified the competitive nature of both individuals. But most important, The Big Miss provides, as Haney says at the tail end of the book, insight into the phenomenon of greatness. Within these pages we see not only the most dominant, charismatic, spiteful person in golf history, but we also get a look into the unique mindset of a truly transformational figure.

Haney writes, “A study of geniuses through history shows their most distinguishing characteristic was a willingness to pay any price until the goal was achieved.”

If we were to sum up Haney’s overall description of Woods, it would be that of a tortured genius uniquely blessed with rare athletic talent yet unable to truly enjoy his success or his place in history.

He is hardly alone. There seems to be a correlation between great success and personal failure that plagues truly gifted people.

On a lesser scale is the socially awkward intellectual perhaps battling undiagnosed Asperger syndrome – a form of autism that allows the person an unnaturally high ability to concentrate on specific tasks but makes them nearly incapable of functioning in social settings – or Nasty Nick Faldo, who before becoming a glib color commentator, was one of the most off-putting people on tour. On the far side of the spectrum is Brian Wilson, the oft-labeled tortured genius whose musical gifts were matched by an equally explosive drug addiction and mental health problems that nearly cost the legendary songwriter his sanity, his soul, and even his life.

I mention these not to suggest that Tiger will build a sand trap in his living room, but to highlight the constant internal battles that often rage within Tiger and other very successful people. These difficulties also are, as Haney says over and over again, what made Woods the greatest golfer in history.

It is psychology, not the titillation, that makes the book an interesting read.