On This Day

(from left) Hawaiian Historical Society vice president Ron Williams Jr., ‘The Hawaiian Journal of History’ editor and former president John Clark, advisor and former president M. Puakea Nogelmeier, president Shari Tamashiro and executive director Jennifer Higa

Deep within the archives of Hawaiian Historical Society is a simple map with a big story.

This particular world atlas was painted in 1838 by David Malo, a prominent Native Hawaiian historian and Christian minister. It’s not especially detailed — it just shows the continents and the oceans. But it is a remarkable piece of history.

“Literacy arrived in Hawaii in 1820,” explains HHS vice president Ron Williams Jr., “So prior to that there was no literacy in Hawaii.

“Less than two decades later, you have Native Hawaiians studying the geography of the world and producing atlases and so forth. That incredible level of academia and education that was going on in Hawaii — something like that really speaks to you.

“We’ve got that original (map).”

And as HHS celebrates its 125th anniversary, it hopes to continue offering knowledge, different perspectives and, most importantly, access to the sprawling history of Hawaii to everyone.

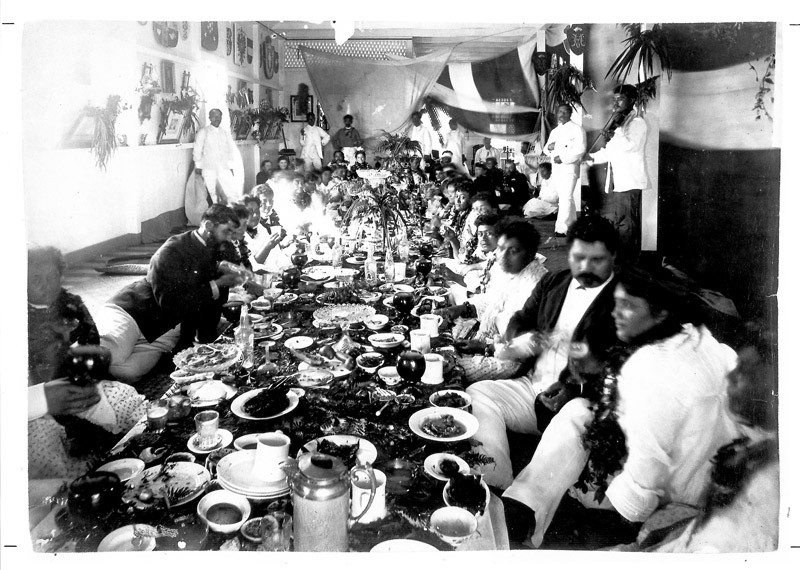

A photo of a luau thrown by King Kalakaua in 1883 (he’s seated at the table’s far end), part of the society’s archives PHOTO COURTESY HHS

The society was founded Jan. 11, 1892, by citizens of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Queen Lili‘uokalani was one of their first patrons. They began gathering and preserving books, newspapers and other materials of historical importance (Queen Emma’s book collection is part of their archives) — a mission that continues till today.

While HHS has particular expertise on the histories of Hawaiians and missionaries in Hawaii, the group emphasizes that it is about much more than that.

“Our mission is Hawaii in the Pacific, Hawaii as a place,” says Williams. “Our mission for the last decade is to expand into the history of the people of Hawaii, period.”

As an example, president Shari Tamashiro cites Yukiko Kimura’s work done on first-generation Japanese immigrants. HHS published an article by Kimura detailing how the husbands of picture brides had to pay $50 to secure their new wives’ admission to the country. Any woman who refused to marry her patron had to repay the $50, but most women arrived without those means.

But a Hawaii law stated that if the couple stayed married for two years, the $50 debt would be forgiven.

“(Kimura) combed all the divorce records — two years to the day,” Tamashiro says. “All these things we had no idea about.”

Another key area of interest is Hawaii’s unique language situation — and how it has affected the history being told today.

“There’s a huge hunger for real history out there,” says Williams. “When I say real history, I mean history that tells us something different than that master narrative.

“After the overthrow happened, there was this concerted effort (by those newly in power) to rewrite Hawaiian history, to talk about how Hawaiians weren’t capable of ruling themselves, because you had to give a reason why a minority should rule Hawaii. … And the only thing they could come up with was that Hawaiians don’t deserve to rule themselves, they can’t — but how do you juxtapose that when there was this incredible, achieving, progressive nation? You get rid of the language.”

Williams estimates that 95 percent of “what we know about Hawaii” has come from English-language texts. But at the time of the overthrow, only 6 percent of the people spoke English as their primary language.

“We’ve gotten 95 percent of our history from 6 percent of the population,” he says. And that has huge repercussions on, well, everything — an entire world unknown to most people today.

The Kingdom of Hawaii, for example, had universal male suffrage in 1852, back when the U.S. was literally heading toward war over the issue of slavery. Political party Hui Kalai‘aina proposed adding female suffrage to the constitution as early as 1890 (Americans got on board with that in 1921).

HHS has made rediscovering and distributing Hawaiian texts a priority. (At one point last year, its board of directors included five fluent Hawaiian speakers.) Every discovery adds a new layer to history, as we know it.

Today, the society gets the word out through channels traditional and new.

HHS maintains its public archives and reading room on the grounds of Hawaii Mission Houses Historic Site and Archives at 560 Kawaiahao St., where anyone is welcome to inquire about or browse materials.

It has published the peer-reviewed The Hawaiian Journal of History for 50 years, the only such Hawaii-focused academic publication of its kind. (After one year, each volume is archived digitally through University of Hawaii.) Plus, the society reprints rare and out-of-print texts, such as Kalua i Ko‘olau.

HHS also hosts regular public lectures by experts, which are filmed and uploaded onto Vimeo, distributes a quarterly newsletter, and publishes a popular calendar that offers a historical tidbit for nearly every day of the year.

But its most popular method of engagement is, of course, Facebook. Boasting some 14,665 likes (as of Jan. 6), it is the fourth most popular historical society on Facebook in the country.

Williams posts regular “Today in Hawaiian History” updates that detail everything from the births and deaths of notable figures, to first Christmas celebrations, criminal cases, notable publications and more in Hawaii.

“What’s amazing is just the connections (the page brings),” Tamashiro says. “So (Hawaiian-language newspaper archivist group) Nupepa always looks at the posts, and they will say, ‘Hey, this is in our collection.’ They add to the conversation. You have regular people from around the world … say, ‘Hey, my grandma talked about this.’

“It’s this wonderful conversation that’s happening where people are so eager to learn.”

To commemorate its 125th anniversary, HHS has planned a special educational campaign on some “hidden heroes” of history.

“A lot of times we honor history makers, and we don’t look at those who were behind the scenes,” Tamashiro muses. “We wanted to find (lesser-known) people who are experts in their niche or area who dedicated themselves to preserving some aspect of our history, and we wanted to shine a spotlight on what they dedicated years of their lives to.”

So, every month this year, HHS will post tributes on its Facebook to men and women of the past and present who have contributed to Hawaii’s history.

First up in January are Te Rangi Hiroa (Sir Peter Henry Buck), former anthropologist at Bishop Museum, and Ben Finney, co-founder of Polynesian Voyaging Society.

“I’m hoping that they serve as inspirational stories, so that a new generation can learn what these people did, and maybe be inspired to do something to preserve history on their own,” Tamashiro says.

HHS admits that the future isn’t always easy — budget cuts in both public and private sectors have added new hurdles in recent years.

“We’re not the Bishop Museum. We don’t have a huge staff and paid employees. We do it because we love the society,” Tamashiro says.

They keep on because the mission is too important to let fade into, well, history.

“The future is in the past,” Williams declares. “Hawaiians revered history because they knew that history brought experience. Whenever they had a problem to face, they asked, ‘How has it been done the last thousand years?’

“Nowadays we get so wrapped up in technology and how it can help us that we think we’re equipped with these tools, that we don’t need the past.

“One of the ways we’ve survived 125 years is reminding the public how relevant history is.”

Hawaiian Historical Society welcomes new members or donations at its website, hawaiianhistory.org.

Check out its Facebook page (facebook.com/hawaiianhistory) for regular updates on events, new publications and, of course, to find out what happened on this day in Hawaii’s history.