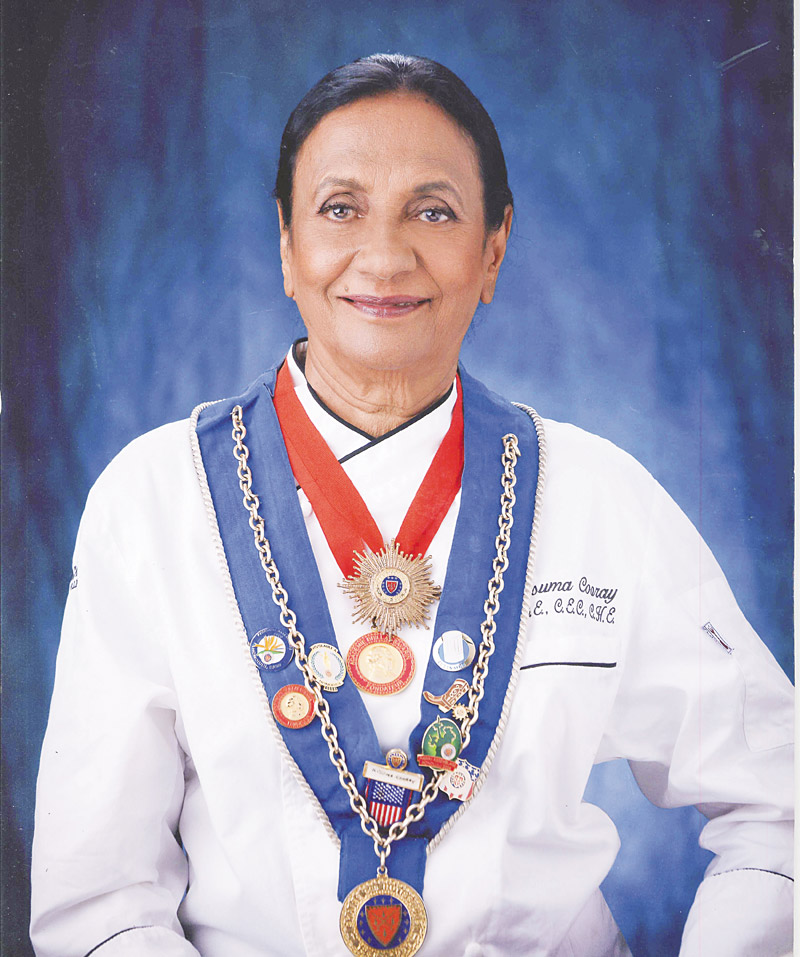

Hawaii Chef Kusuma Cooray Was Born With The Taste Of Gold

She’s cooked for royalty, celebrities and the very wealthy, but Kusuma Cooray’s real joy in life is teaching, and thanks to her work at KCC over the past 28 years, the culinary program will be moving into an amazing new facility, Culinary Institute of the Pacific

Not everyone is born with the taste of gold, but celebrated Hawaii chef Kusuma Cooray was. After three boys, her parents finally welcomed a girl to their Sri Lankan home. As was the family custom, they wrapped her in a silken cloth that had swaddled generations of the family’s newborns, and her father ceremoniously ground dust from a sovereign gold coin, mixed it with mother’s milk — forming ran-kiri, literally “gold milk” — and applied it to baby Kusuma’s lips.

That blessed palate would grow to become so intimately aware of the finest nuances of food preparation — from flavor melding, to perfection of texture, dish pairing and presentation — that Cooray would be chosen as tobacco heiress Doris Duke’s personal chef, before becoming a professor with Kapiolani Community College’s Culinary Arts Program. There, she trained myriad of Hawaii’s current food and beverage industry experts for nearly 30 years. Cooray also has cooked for the likes of Prince Charles and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and was Julia Child’s personal friend and dinner guest — indeed, Child once prepared a private dinner just for Cooray.

A trailblazing food maven, Cooray was among America’s first handful of female executive chefs certified by American Culinary Federation, and Hawaii’s very first. When Cooray first came through Hawaii, she was heading home to Sri Lanka after studying culinary arts in England and France. But Oahu held her fate and fortune. It was on this paradisiacal isle that she would meet and marry Ranjit, a botanist earning his graduate degrees as an exchange student at UH. He was a fellow Sri Lankan, who coincidentally hailed from her own hometown. The timing was serendipitous for Cooray’s career as well, as Duke had been looking for a personal chef.

Cooray’s taste buds were cultivated and refined from an early age. Her family was well-to-do. Father was a businessman and mom tended to the house, complete with maids and cooks. Summer vacations were long, and though children were not allowed in the kitchen, Cooray was not to be deterred.

“I loved cooking so much; I wanted to go into the kitchen and mess around. I still remember the spices — a whole range,” she recalls. “At 9 years of age, they used to let me be in the kitchen and do little things, and by 10 years old I could do a little dish. That’s how I first started … apprenticing as a child.”

This was during Sri Lanka’s period of British rule. As Cooray grew older, she was mesmerized by the idea of cooking, but women in Sri Lanka did not enter the work-force. Even as a youngster, she was struck by magazine covers depicting people with tall hats. It turns out they were students of Le Cordon Bleu, the world’s largest hospitality school. As soon as she had the chance, Cooray journeyed to London and studied in that prestigious institution, before moving on to France, where she apprenticed at the famous Henri IV restaurant in Chartres.

A natural at stirring up fragrant Asian curries, and now with continental cuisine under her belt, Cooray arrived in Hawaii ripe for a position with Doris Duke. Duke so loved Cooray’s cooking, that even while the heiress traveled between her many estates all over the world, she had Cooray accompany her. Cooray has since published two award-winning books — one on spices and one on seafood — where she dedicates recipes to personalities for whom she cooked. There’s Asparagus Mousse she made for Prince Charles when he visited Sri Lanka on the country’s 50th Independence Day celebration, or Caviar Bites Nureyev she prepared for the Russian dancer at a cocktail party at Duke’s Shangri-La, here in Hawaii. She also cooked for dancer Martha Graham, and a tomato soup for “Jacquie” Kennedy Onassis. Then, there’s the fondly named Herb Salad Doris she often prepared for the woman the rest of us refer to as Duke.

Duke had a penchant for freshness. While she’d airlift rare ingredients from Sri Lanka — like curry leaves and jaggery — at the bequest of Cooray those 30 years ago, Duke also took the concept of farm-to-table to its zenith.

“There were cornfields at her place in Newport, Rhode Island,” says Cooray. “From the kitchen window we could see her going for a bath in the Atlantic Ocean. The instructions were, when we see her coming back, the gardener cuts the corn and brings it to the kitchen. She sits at the table and the corn goes from the pot to her. It was my dream job. Who else can have a job like that?”

After working for Duke, any party knew they’d be lucky to get their cooking mitts on Cooray. The Willows restaurant first snapped her up as executive chef. Then she became a culinary professor at KCC some 28 years ago. Her illustrious career has since only blossomed. Cooray’s list of gastronomic accolades and awards has perhaps more dazzle to it than a stainless steel kitchen.

Among her many accomplishments are phenomenal honors, including winning the Burton trophy of excellence from London’s National Bakery School and the coveted Brillat Savarin medal awarded by Chaine des Rotisseurs (the standard of merit for fine cuisine), and most recently, the Chaine des Rotisseurs’ Gold Star for her work in mentoring Hawaii’s young chefs.

Being Asian, and a woman, in a European man’s world never fazed Cooray.

“When I was awarded the Burton trophy,” she notes, “it was the first time an Asian won … an Asian woman was unheard of!”

Cooray has no problem confronting new territory when it comes to recipes, either. In fact, mixing east and west cooking traditions is what she likes best. Some

20 years ago, she opened the popular Ka ‘Ikena Laua‘e dining room at KCC, featuring fusion dishes. It’s a place for students to practice their skills with real-world dining, and it’s been so successful that reservations are hard to come by. Given her flair for hosting dinners, her appreciation of her Asian roots and the fact that she serves as honorary consul for Sri Lanka, Cooray has been bringing banquets and special galas to KCC throughout the year, from an annual Consul Corps International evening (coming up Oct. 8), representing the diverse student body on campus, to major celebrations welcoming diplomatic VIPs from her home country.

Cooray retired from KCC this past May, but retirement is only a word, considering that this queen of cuisine is as busy as ever and with new projects on the horizon, including a book on accompaniments — like relishes, chutneys and pickles — coming out next year.

“The best part of my career has been teaching,” notes Cooray, “to really give back.”

And give she has, as fellow KCC culinary arts professor and department chairman Ronald Takahashi can attest.

“Kusuma was one of our key instructors,” says Takahashi, who joined the faculty at the same time as Cooray. “The hallmark of our program is that we hire instructors who have a tremendous amount of industry experience. Kusuma has been a vital part of our ability to train students in all aspects of cooking. The quality of what she cooks is outstanding. She has some of the best flavors and tastes around.”

Cooray helped Hawaii’s food industry burgeon from the first culinary training program in the state to having subsidiary programs on the Neighbor Islands, and an ever-flourishing four-year program on Oahu. So flourishing, in fact, that the program needs a new home, and that home is at hand. A state-of-the art facility, named Culinary Institute of the Pacific, 20 years in the works, will open in the next couple of years at the base of Diamond Head, the site of the old Cannon Club. The program’s current staff of 14 full-time instructors and many adjuncts, along with 450 or so students, has outgrown their current facility. The new one will provide room for growth, including starting an advanced pastry arts program.

Meanwhile, the program nurtures its competitive division, with students vying to win state, regional and national competitions — often winning at the state and regional levels, and even winning the national title in 2009. The culinary program has developed a true community interface, offering workforce-development programs (getting students into the field), getting involved in childhood obesity projects and sustainable agriculture, as well as maintaining an international relationship with culinary programs around the world.

“Kusuma is not quietly riding off into the sunset,” says Takahashi. “She’s keeping in touch with the industry, and I’m sure she’ll continue to provide advice and her level of expertise to us as we meet future challenges.”

Not only will Cooray remain actively involved with the college and community hospitality industries, but she also has ensured that she continue to support the program she so lovingly shaped into perpetuity. Truly, Cooray’s is a love story, both for her husband of 25 years, who passed away in 2001, and for cooking, particularly in regard to training up-and-coming chefs. She has united those two loves by forming the Ranjit and Kusuma Cooray Endowed Scholarship (uh-foundation.org/givetokcc).

“It was Ranjit who encouraged Kusuma to go into teaching,” says UH Foundation president and CEO Donna Vuchinich. “It was his wish that she create this endowment and assist those who would come after them. It will provide multi-year scholarships to students enrolled in the culinary arts program at KCC.

“Kusuma is all about giving back. She is an inspiring individual — when you’re in her presence, to feel her warmth and her understanding of culinary preparation and quality, of food delivery and presentation — she’s absolutely elegant.”

That elegance shines, not just in her expertise at presenting mouthwatering dishes, but in her personal life as well, whether she’s entertaining at a social gathering dressed in a traditional sari, or engaged in competitive ballroom dancing, which she did for several years after her husband’s passing. But most impressive, it surfaces in her demeanor. Here is a woman who has literally cooked for princes and princesses, and yet, unlike the harried image we see of chefs in today’s reality shows, Cooray exudes calmness mixed with an endearing pride for perfectionism:

“I was never nervous,” she responds, when asked whether it was intimidating to cook for some of the world’s most consequential personages. “I was so thrilled. Even then, I was very confident. I believe in good taste. People who know my food know that anything I touch is always tasty.

“People come to me and say, ‘This was a long time ago, but I tasted one of your appetizers. I’ll never forget. It was fresh pears, sliced, put together again, cooked under a broiler with a blue cheese topping, then dressed up.’ People remember. You get to a person’s heart through food.”

When it comes to Kusuma Cooray, heart and food intertwine seamlessly. And food establishments throughout Hawaii, and across the globe, are reaping the benefits of her groundbreaking successes early on, and her continuing love for creating unforgettable connections over sumptuous cuisine.