Getting Serious About Concussions

I have written previously about the good work that Hawaii’s athletic trainers are doing to help coaches and athletes learn about the effect of concussions.

“Since 2010, the athletic trainers have been doing baseline testing (cognitive and balance) on contact sport athletes,” says Ross Oshiro, state DOE Athletic Health Care trainer and coordinator.

I followed up with Oshiro after watching a disturbing video on YouTube called Casualties of the Gridiron, a documentary series aired this year by GQ.com. The series showcased the effects of brain trauma suffered by a number of former NFL and college football stars — brain trauma primarily brought on by concussions while playing.

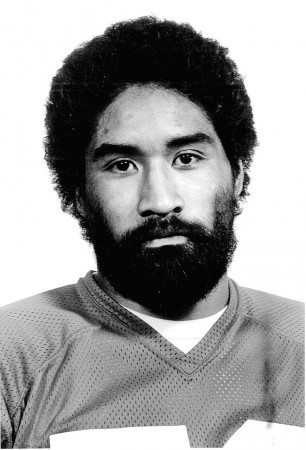

The story that disturbed and fascinated me the most was about Terry Tautolo, a nine-year NFL veteran and former UCLA All-American line-backer, who played for the San Francisco 49ers’ first Super Bowl championship team in 1981-82. Tautolo also played for Philadelphia Eagles, Miami Dolphins and Detroit Lions, and often was credited with being one of the key Samoans to blaze the trail for long careers in the NFL.

Hawaii Kai’s Barry Markowitz played with Tautolo at UCLA in the early ’70s. “He was catlike in his quickness,” Markowitz recalls. “We were great friends and he was in my wedding.”

Tautolo’s NFL career ended with a severe head injury in the mid-’80s. Two decades later, he was homeless. The video documentary showed a haggard, toothless and frail 60-year-old who looked much older.

“I was homeless for a couple of years; that was my fault,” Tautolo says. “Football is a great game. The only thing bad about football is the concussions.”

To be fair, it’s not clear whether all Tautolo’s sufferings were caused by hits on the field. He also struggled with a drug problem, including meth use. But when word got out that he was homeless and living under a freeway overpass in Los Angeles, several former football friends, some of whom also had suffered from the effects of severe concussions and other issues, reached out to help him.

Tautolo entered a program called P.A.S.T., an acronym for Pain Alternatives, Solutions and Treatment. He admitted his meth use and vowed to stop it. Others joined in to help, including Dick Vermeil, his coach at UCLA and Philadelphia. A video of Vermeil and Tautolo working together several months after the first documentary aired shows the former linebacker has improved considerably. He is now reportedly living in a sober environment in Southern California.

Tautolo’s improvement contrasts sharply with the tragic suicide of Junior Seau, who suffered tremendously with depression and other ailments most likely brought on by severe concussions. There have been other side effects, too, like Jim McMahon’s reported early-onset dementia. This past summer, the NFL settled with many of its former players in a class-action suit that grants up to $675 million in damages to more than 4,000 former players. The NFL veterans have until Oct. 14 to opt in to the agreement.

In the meantime, stories like Tautolo’s and others showcase the importance of education.

“Schools (now) provide annual concussion education for coaches and parents at their annual preseason meetings,” says Oshiro.

New rules also have gone into place in the NCAA, the NFL, high schools and youth leagues. And helmet manufacturers have ramped up efforts to provide more protection, too. Families of loved ones suffering lingering issues from a violent game they played years ago are encouraged to seek immediate help.

The efforts are appreciated by those who love the hard-hitting game of football. But whether it’s too little, too late for those who gave it their all in the decades before, only time will tell.

senatorbobhogue@yahoo.com