UH vs. Ebola

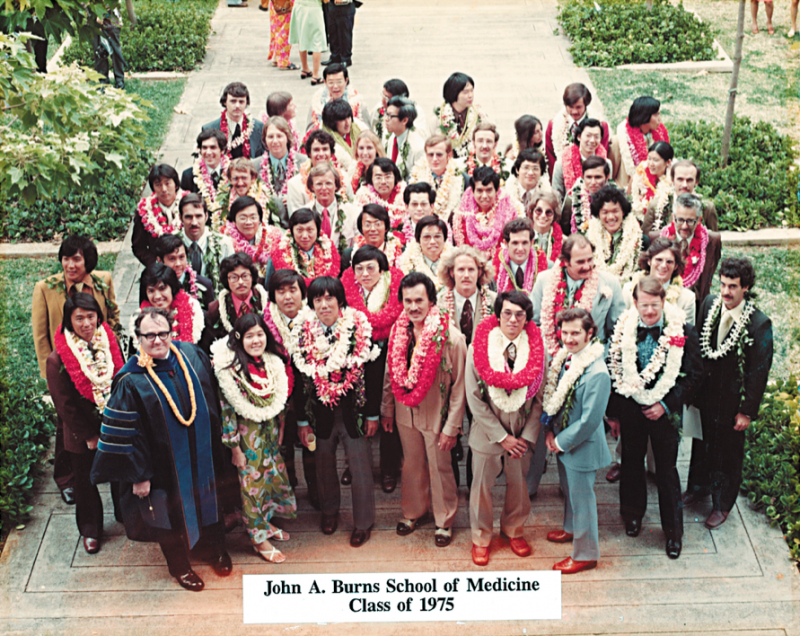

Celebrating 50 years, JABSOM has made itself known as a leading medical school in the nation. And with an Ebola vaccine currently in development at its Kakaako campus, JABSOM is on the path to making a difference in medicine

It was Dec. 26, 2013, in Meliandou, Guinea, when an 18-month-old boy developed a fever. Two days later, Ebola had taken his life.

This, says World Health Organization, is where it all began. In the weeks that followed, the illness spread rapidly to become what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has classified as the largest Ebola outbreak in history. The media attention it received and subsequent frenzy after Ebola made its way into the U.S. made it feel new — surreal, almost.

But the reality is that Ebola already had existed for almost 40 years in Africa, having first been discovered in 1976. And here in Hawaii, halfway around the world, development of a vaccine for the deadly disease was well underway at John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM) at University of Hawaii.

With the school celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, this research is only one of a number of achievements currently putting JABSOM in the spotlight. For three years, it has ranked No. 1 in the National Institutes of Health research awards for public medical schools without a university hospital. Just recently, U.S. News & World Report ranked it No. 19 in the nation as a top medical school, up from last year’s No. 57 spot.

“We’re very excited,” says JABSOM dean and University of Hawaii Cancer Center interim director Dr. Jerris Hedges, on the school reaching this 50-year milestone.

“We have a lot to be proud of.”

EBOLA: A DISEASE

Around last September, Dr. Axel Lehrer answered questions from local reporters in an attempt to ease public concern over Ebola. It was, he recalls telling them, most likely to stay within Africa and not affect the U.S.

A few weeks later, the first case of Ebola in the U.S. was reported.

Fortunately, it did not reach epidemic conditions in the U.S., but the truth is, Lehrer admits, you just don’t know when the next public health crisis will occur.

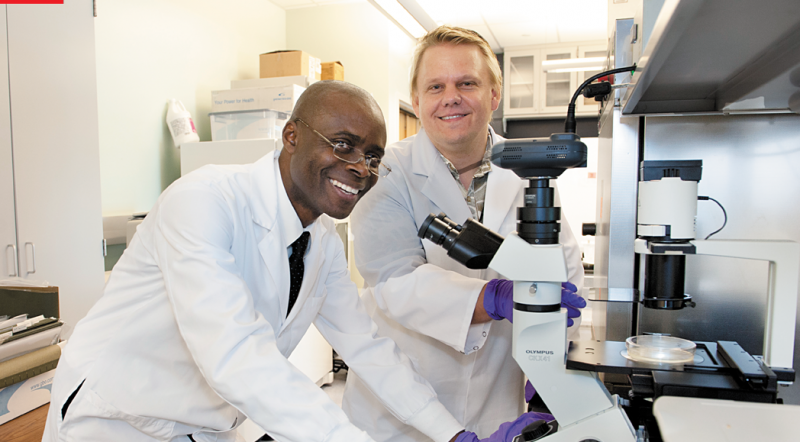

He began developing a filovirus vaccine for Ebola 12 years ago while working for Hawaii Biotech Inc. Last year, he joined the Department of Tropical Medicine, Medical Microbiology and Pharmacology at JABSOM, and in May the school announced it would partner with Hawaii Biotech to continue work on the vaccine.

In 2005, the recombinant subunit vaccine reached efficacy after successfully protecting mice. Though it is important to note that there is no infective virus in Hawaii and that all testing by JABSOM is done by collaborators on the Mainland.

The next step, says Lehrer, is clinical testing on humans, a process that may take around 12-18 months. It’s easier said than done, though, when he estimates that it will cost roughly $3 million to $5 million to get the vaccine into a clinic, and another $12 million more to complete testing.

It’s even more difficult because funding for the vaccine has been difficult at times.

“Because I have really been working on this for a long time, it certainly … is satisfaction that you feel,” says Lehrer. “But I’m also acutely aware of all the struggles.

“I wish that our biggest obstacle — and it is a simple one, it is funding — would be relieved because we really think that we have a very good solution to the problem in our hands,” he adds.

If it tests successfully in humans, Lehrer and his team will have created a vaccine that stands out among others in development for a few reasons.

First, the recombinant subunit vaccine may be given to anyone in any age range regardless of pre-existing health conditions like autoimmune diseases or HIV. Second, unlike vaccines that prevent against diseases like hepatitis, Lehrer’s vaccine may be used to boost itself or other vaccines.

Finally, the vaccine relies on purified recombinant proteins produced in insect cells. As a result, the final product is very stable.

This is one outcome that last month attracted another partnership for JABSOM with Soligenix Inc. Lehrer, with help from Soligenix, is exploring the potential for his vaccine to not require refrigeration. If it proves successful, Lehrer’s vaccine would not only prove extremely useful in areas it is needed most, but could drastically affect medical practices in general.

“Our immune memory is something that you can easily mislead,” adds Lehrer. “So it is very, very important for a vaccine to be right on target. That’s what it looks like we’re able to generate with this.”

EBOLA: A SOCIOLOGICAL CONCERN

To understand Ebola as it is in Africa is to know that all cultures are not alike. More than 85 percent of Africans, for instance, are likely to see a traditional healer before a medical professional.

The burial process also is different. In Africa, a person who has died is believed to have achieved a higher state of being. It’s tradition, therefore, to wash and prepare a body for that transition, and to show love by kissing and caressing the body.

And like any metropolis, the further away you are, the less access you have to things like modern communication and healthcare.

So maybe a person hugging the body of someone who died of Ebola had a cut. Or a healthcare worker dressed in protective gear arrived to take away bodies of loved ones before a family could complete burial rites (thus instilling mistrust, making people less inclined to seek professional medical help). Or a village is simply further away from cities and received misinformation, or slow information, about the disease.

All of this was, argues Dr. Felix Ikuomola of Nigeria, a major impetus for the spread of Ebola in rural areas in Africa — places like Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea.

“To really prevent another outbreak of Ebola and all the communicable diseases, we need to bring in culture,” says Ikuomola. “We need to understand the socioeconomic factors of these people.”

Ikuomola, already a medical doctor, currently is working toward a Ph.D. in clinical research at JABSOM and will publish a book on these very societal concerns. Titled The Ebola Virus and West Africa: Medical and Sociocultural Aspects, it is slated for release next month.

“I also have a mind of going to Africa to give the government leaders and policy leaders (ideas of) how we can move forward in our cultural modification,” he says. “We can kind of be proactive instead of waiting for when we have a problem.”

EBOLA: AN EXAMPLE

When you look at the work that Lehrer and Ikuomola have accomplished, the result is a synergy that encapsulates all that JABSOM aspires to instill in its students as an institution — that this isn’t merely a place for future doctors to learn, but one that also fosters growth and relationships within the community.

Because it does not have a university hospital, for example, JABSOM works with local hospitals to train students. Through JABSOM and its Cancer Center, the school also has formed an alliance with The Queen’s Medical Center, Hawaii Pacific Health and Kuakini Medical Center to combat cancer.

And the bridge between medicine and culture that Ikuomola hopes to encourage in Africa already is taking place at JABSOM. The Native Hawaiian community in particular is one JABSOM has worked with for more than a decade through its Department of Native Hawaiian Health. It is the only program of its kind in the nation that is devoted to improving the health of an indigenous population.

“This department is a leader in terms of helping introduce not only cultural issues into our curriculum, but also connecting us with the community and grounding us with the community,” says Hedges.

The school, he notes, constantly has been evolving.

In its future, JABSOM is looking to expand its graduate medical experience and other possible fellowship opportunities. Work like Lehrer’s also makes Hedges hopeful that continued research efforts will create cutting-edge scientific job opportunities within the state.

“A lot of that will depend upon doing some unique collaboration with commercial entities, like that partnership that (Lehrer) developed with Hawaii Biotech. That’s the sort of thing we want to see continue to develop,” says Hedges.

“This whole complex was built on the idea of the school evolving beyond its role of educating physicians to also have a significant impact on the science that’s developed in Hawaii for Hawaii,” he adds of the school’s Kakaako campus that opened in 2005. (The school initially opened at Leahi Hospital.)

It’s a seemingly lofty goal being brought to reality at JABSOM that Hedges credits largely to the school’s faculty and staff — 1,200 of whom are volunteers. Ultimately, it is they who will pave the way for future generations of doctors, researchers and scientists, and it is a testament to their commitment to work for and with the community.

“Often people say, ‘Oh, what are we giving back to the community,’” says Lehrer. “You have a reason you want to research something and why you’re fascinated by it. Us now, as faculty here, we are the ones to bring that fascination from our generation to the next.”

JABSOM hosts its 50th anniversary gala Saturday, July 18, at Sheraton Waikiki. All proceeds from the evening will go to scholarships for students. To attend and for more information, visit jabsom.hawaii.edu/ 50thanniversary/gala/.