The Day Duke Became A True Hero

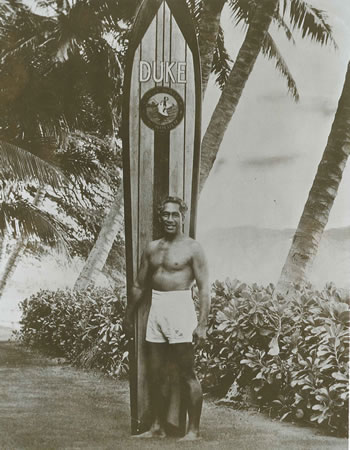

Duke in Waikiki. Joe Brennan Collection / Photo courtesy Jim Gaddis

We are all aware of his statue in Waikiki, of the restaurant named after him, and his legendary status as a surfer, paddler and Olympic swimmer, but did you know the story of Duke Kahanamoku’s most incredible achievement?

This week marks the 87th anniversary of a life-saving effort by Hawaii’s greatest athlete that happened in an ocean far away from Duke’s Oahu home. It was June 14, 1925, along the shores of Corona Del Mar in Newport Beach, Calif., where the 34-year-old Olympian gathered with a few of his actor and actress friends from Hollywood for a day of surfing. Just a few years before, Duke had helped popularize the sport in Southern California as he lugged the giant boards that often weighed between 100 and 200 pounds to the southland’s sandy beaches. Corona Del Mar was one of his favorite surf spots as the waves often built up along a sand-bar that was then offshore.

Duke just happened to have his surfboard in hand when the waves became in his words “building up to barnlike heights.” In an interview described by biographer Malcom Gault Williams, Duke says, “From shore, we suddenly saw the charter fishing boat, the Thelma, wallowing in the water, trying to get to safe water and it was a losing battle.”

The boat was filled with more than two dozen fishermen, and when it suddenly capsized and its passengers were tossed into the water, Duke jumped into action.

“Fully clothed persons have little chance in a wild sea like that,” he was quoted as saying. “Neither me nor my pals were thinking about heroics, we were simply running – me with my board and the others to get their boards – hoping to save lives. Don’t ask me how I made it, for it was just one long nightmare of trying to shove through what looked like a low Niagara Falls.”

Duke furiously paddled through the gigantic waves, oblivious to his own safety. Miraculously, he made one trip after another into the churning surf, pulling as many to safety as he could.

“I brought one victim on my board, then two on another trip, possibly three on another, then back for one. It was a delirious shuttle system,” he says. “In a matter of minutes we were making rescues; (people were) screaming, gagging, thrashing. Some victims we could not save at all. We lost count of the number of trips we made. Without the boards, we would probably not have been able to rescue a single person.”

In all, 17 people drowned that day, but incredibly Duke and his friends were able to save 12 potential drowning victims. Duke was credited with saving eight of those himself. Befitting his humble personality, he didn’t stick around to try to grab headlines. He left the scene before reporters even arrived.

The Newport Beach chief of police, Capt. James Porter, was quoted in the local newspapers: “Kahanamoku’s performance was the most superhuman rescue act and the finest display of surfboard riding that has ever been seen in the world.”

In a front page article in the Los Angeles Times years later, writer Dial Torgerson said, “His role on the beach that day was more dramatic than the scores he played in four decades of intermittent bit-part acting in Hollywood films. That day, he was the star.”

Duke’s heroic efforts also helped spread the word about the tremendous value of surfboards in water safety, and soon lifeguards around the world would be equipped with boards as part of their rescue efforts.

The legend, and real-life heroics, of the Father of Surfing, Duke Kahanamoku, live on to this day, on both sides of the Pacific.